Prof. Muhammad Shamsaddin Megalommatis

Tuesday, 27 December 2022

Outline

Introduction; Iranian Achaemenid historiography; Problems of historiography continuity; Iranian posterior historiography; foreign historiography; Western Orientalist historiography; early sources of Iranian History; Prehistory in the Iranian plateau and Mesopotamia

1- Introduction

Welcome to the 40-hour seminar on Achaemenid Iran!

It is my intention to deliver a rather unconventional academic presentation of the topic, mostly implementing a correct and impartial conceptual approach to the earliest stage of Iranian History. Every subject, in and by itself, offers to every researcher the correct means of the pertinent approach to it; due to this fact, the personal background, viewpoints and thoughts or eventually the misperceptions and the preconceived ideas of an explorer should not be allowed to affect his judgment.

If before 200 years, the early Iranologists had the possible excuse of studying a topic on the basis of external and posterior historical sources, this was simply due to the fact that the Old Achaemenid cuneiform writing had not yet been deciphered. Still, even those explorers failed to avoid a very serious mistake, namely that of taking the external and posterior historical sources at face value. We cannot afford to blindly accept a secondary historical source without first examining intentions, motives, scopes and aims of it.

As the seminar covers only the History of the Achaemenid dynasty, I don’t intend to add an introductory course about the History of the Iranian Studies and the re-discovery of Iran by Western explorers of the colonial powers. However, I will provide a brief outline of the topic; this is essential because mainstream Orientalists have reached their limits and cannot provide us with a real insight, eliminating the numerous and enduring myths, fallacies, and deliberately naïve approaches to Achaemenid Iran.

In fact, most of the specialists of Ancient Iran never went beyond the limitations set by the delusional Ancient ‘Greek’ (in reality: Ionian and Attic) literature about the Medes and the Persians (i.e. the Iranians), because they never offered themselves the task to explain the reasons for the aberration that the Ancient Ionian and Attic authors created in their minds and wrote in their texts about Iran. This was utterly puerile and ludicrous.

And this brings us to the other major innovation that I intend to offer during this seminar, namely the proper, comprehensive contextualization of the research topic, i.e. the History of Achaemenid Iran. To give some examples in this regard, I would mention

a – the tremendous, multilayered and multifaceted impact of the Mesopotamian World, Civilization and Heritage on the formation of the Achaemenid Empire of Iran, and more specifically, the determinant role played by the Sargonid Empire of Assyria on the emergence of the first Empire on the Iranian plateau;

b – the ferocious opposition of the Mithraic Magi to the Zoroastrian Achaemenid court;

c – the involvement of the Anatolian Magi in the misperception of Iran by the Ancient Greeks; and

d- the utilization of the Ancient Greek cities by the Anti-Iranian side of the Egyptian priesthoods, princes and administrators.

To therefore introduce the proper contextualization, I will expand on the Neo-Assyrian Empire and the Sargonid times, not only to state the first mentions of the Medes and the Persians in History, but also to show the importance attributed by the Neo-Assyrian Emperors to the Zagros Mountains and the Iranian plateau, as well as the numerous peoples, settled or nomadic, who inhabited that region.

There is an enormous lacuna in the Orientalist disciplines; there are no interdisciplinary studies in Assyriology and Iranology. This plays a key role in the misperception of the ancient oriental civilizations and in the mistaken evaluation (or rather under-estimation) of the momentous impact that they had on the formation of the World History. There are no isolated cultures and independent civilizations as dogmatic and ignorant Western archaeologists pretend.

Only if one studies and evaluates correctly the colossal impact of the Ancient Mesopotamian world on Iran, can one truly understand the Achaemenid Empire in its real dimensions.

2- Iranian Achaemenid historiography

A. Achaemenid imperial inscriptions produced on solemn occasions

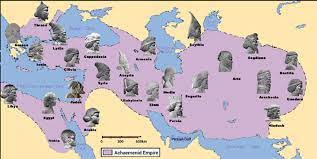

Usually multilingual texts written by the imperial scribes of the emperors Cyrus the Great, Darius I the Great, Xerxes I, Artaxerxes I, Darius II, Artaxerxes II, and Artaxerxes III, as well as of the ancestral rulers Ariaramnes and Arsames.

Languages and writing systems:

– Old Achaemenid Iranian (cuneiform-alphabetic; the official imperial language)

– Babylonian (cuneiform-syllabic; to offer a testimony of historical continuity and legitimacy, following the Conquest of Babylon by Cyrus the Great, who presented himself as king of Babylon)

– Elamite (cuneiform-logo-syllabic; to portray the Persians in particular as the heirs of the ancient land of Anshan and Sushan that the Assyrians and the Babylonians named ‘Elam’ and the indigenous population called ‘Haltamti’ / The first Achaemenid to present himself as ‘king of Anshan’ is Cyrus the Great and the reference is found in his Cylinder unearthed in Babylon.)

and

– Egyptian Hieroglyphic (if the inscription or the monument was produced in Egypt, since the Achaemenids were also pharaohs of Egypt, starting with Kabujiya/Cambyses)

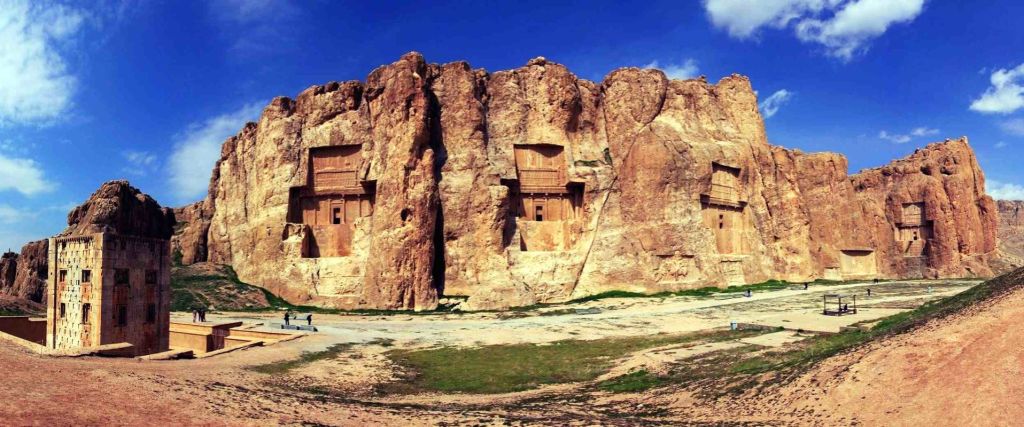

Imperial inscriptions are found in: Babylon (Cyrus Cylinder), Pasargad, Behistun, Hamadan, Ganj-e Nameh, Persepolis, Naqsh-e Rustam, Susa, Suez (Egypt), Gherla (Romania), Van (Turkey), and on various items

B. Persepolis Administrative Archives

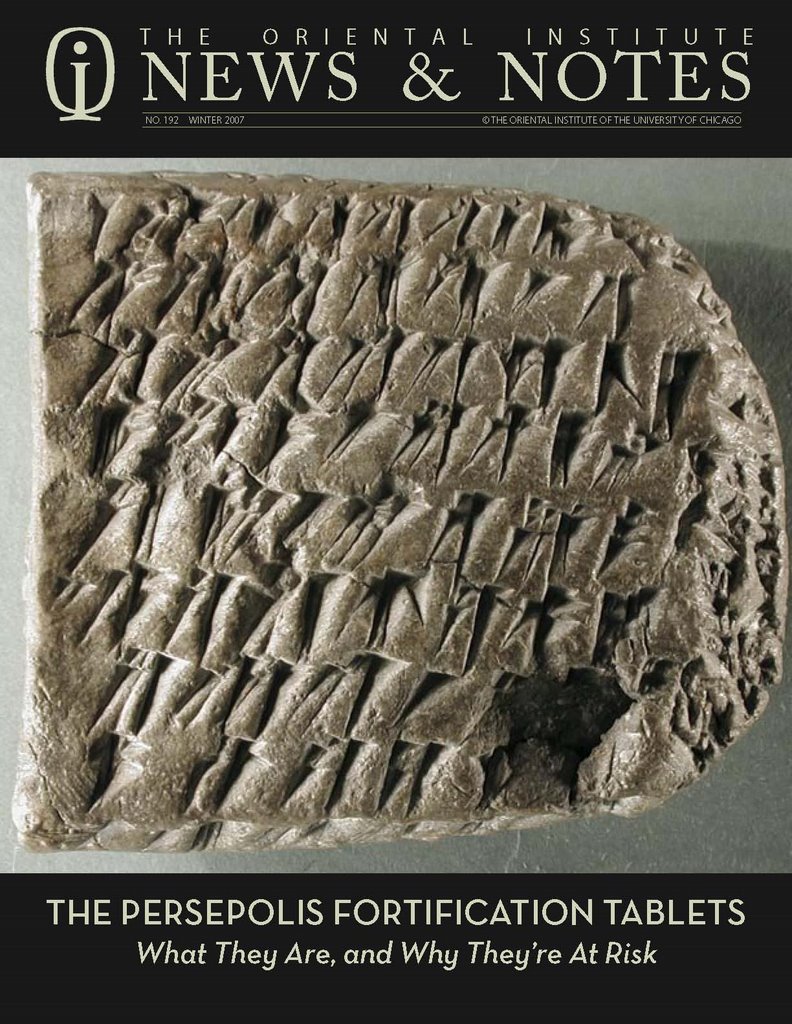

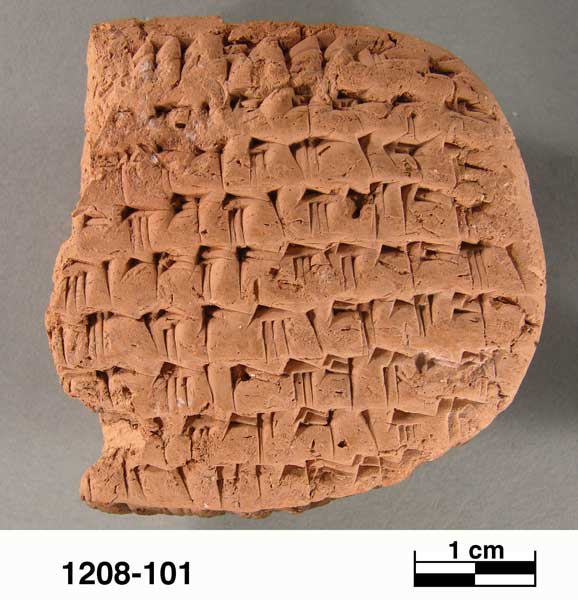

This consists in an enormous documentation that has not yet been fully studied; it is not written in Old Achaemenid as one could expect but mainly in Elamite cuneiform. It consists of two groups, namely

– the Persepolis Fortification Archive, and

– the Persepolis Treasury Archive.

The Persepolis Fortification Archive was unearthed in the fortification area, i.e. the northeastern confines of the enormous platform of the Achaemenid capital Parsa (Persepolis), in the 1930s. It comprises of more than 30000 tablets (fragmentary or entire) that were written in the period 509-494 BCE (at the time of Darius I). The tablets were written in Susa and other parts of Fars and the territory of the ancient kingdom of Elam that vanished in the middle of the 7th c. (more than 130 years before these texts were written). Around 50 texts had Aramaic glosses. More than 2000 tablets have been published and translated. These texts are records of transactions, distribution of food, provisioning of workers, transportation of commodities, etc.; few tablets were written in other languages, namely Old Iranian (1), Babylonian (1), Phrygian (1) and Greek (1).

The Persepolis Treasury Archive was found in the northeastern room of the Treasury of Xerxes. It contains more than 750 tablets and fragments (in Elamite) and more than 100 have been published. They all date back in period 492-458 BCE. These tablets are either letters or memoranda dispatched by imperial officials to the head of the Treasury; they concern the payment of workmen, the issue of silver, and other administrative procedures. Only one tablet was written in Babylonian.

The entire documentation offers valuable information as regards the function of various imperial services, namely the couriers, the satraps, the imperial messengers, the imperial storehouse, etc. The archives shed light on the origin of the imperial administrators, as ca. 1900 personal names have been recorded: 10% were Elamites (who had apparently survived for long far from their country after the destruction of Susa by Assurbanipal (640 BCE), fewer were Babylonians, and the outright majority consisted of Iranians (Persians, Medes, Bactrians, Sakas, Arians, etc.).

C. Imperial Aramaic

The diffusion of the use of Aramaic started already in the Neo-Assyrian times and during the 7th c. BCE; the creation of the ‘Royal Road’, the systematization of the transportation, the improvement of communications, and the formation of the network of land-, sea- and desert routes that we now call ‘Silk-, Spice- and Perfume- Road’ during the Achaemenid times helped further expand the use of Aramaic. The linguistic assimilation of the Babylonians, the Jews and the Phoenicians with the Aramaeans only strengthened the diffusion of the Aramaic, which became the second international language (‘lingua franca’) in the History of the Mankind (after the Akkadian / Assyrian-Babylonian). Gradually, Aramaic became an official Achaemenid language after the Old Achaemenid Iranian.

Except the Aramaic texts attested in the Persepolis Administrative Archives, thousands of Aramaic texts of the Achaemenid times shed light onto the society, the economy, the administration, the military organization, the trade, the religions, the cults, the culture and the spirituality attested in various provinces of the Iranian Empire. At this point, only indicatively, I mention few significant groups of texts:

– the Elephantine papyri and ostraca (except Aramaic, they were written in Hieratic and Demotic Egyptian, Coptic, Alexandrian Koine, and Latin) – 5th and 4th c. BCE,

– the Hermopolis Aramaic papyri,

– the Padua Aramaic papyri, and

– the Khalili Collection of Aramaic Documents from Bactria (48 texts written on leather, papyrus, stone or clay, dating from the period 353-324 BCE, and mainly from the reign of Artaxerxes III whereas the most recent dates from the reign of Alexander the Great).

Here I have to add that the widespread use of Imperial Aramaic and its use as a second official language for Achaemenid Iran brought an end to the use of the Elamite (in the middle of the 5th c.) and, after the end of the Achaemenid dynasty and the split of the state of Alexander the Great, contributed to the formation of two writing systems, namely Parthian and Pahlavi which were in use during the Arsacid and the Sassanid times. Imperial Aramaic helped establish many other writing systems, but this goes beyond the limits of the present seminar.

3- Problems of historiography continuity

There are no historical references to the Achaemenid dynasty made at the time of the Arsacids (Ashkanian: 250 BCE-224 CE) and the Sassanids 224-651 CE); this situation is due to many factors:

– the prevalence of another Iranian nation of probably Turanian origin, namely the Parthians and the Arsacid dynasty,

– the rise of the anti-Achaemenid, anti-Zoroastrian Magi who tried to impose Mithraism throughout Iran during the Arsacid times,

– the formation of an oral epic tradition and the establishment of a legendary historiography about the pre-Arsacid past during the Sassanid times, and

– the scarcity of written sources and the terrible destructions that occurred in Iran during the Late Antiquity, the Islamic era, and the Modern times (early Islamic conquests, divisions of the Abbasid times, Mongol invasions, Safavid-Ottoman wars, Western colonial looting, etc.).

This situation raised Western academic questions of Iranian identity, continuity, and historicity. But this attempt is futile. Iranian historiography of Islamic times shows that these questions were fully misplaced.

4- Iranian posterior historiography (Iranian historiography of Islamic times)

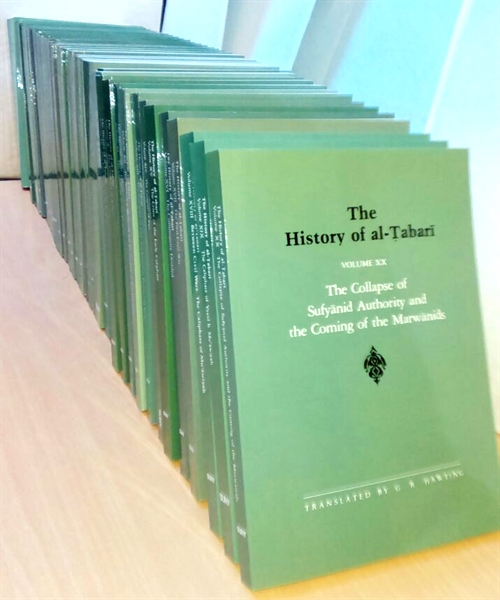

With Tabari (839-923) and his voluminous History of Prophets and Kings we realize that there were, in spite of the destructions caused because of the Islamic conquests, historical documents on which he was based to expand about the Sassanid dynasty; actually one out of the 40 volumes of the most recent translation of Tabari to English (published by the State University of New York Press from 1985 through 2007) is dedicated to the History of Sassanid Iran (vol. 5). And the previous volume (vol. 4) covers the History of Achaemenid and Arsacid Iran, Alexander the Great, Nabonid Babylonia, Assyria and Ancient Israel and Judah.

Other important Iranian historians of the Islamic times, like Abu’l-Fadl Bayhaqi (995-1077), Rashid al-Din Hamadani (1247-1318) who wrote the truly first World History, Alaeddin Aṭa Malik Juvaynī (1226-1283), and Sharaf ad-Din Ali Yazdi (ca. 1370-1454), did not expand much on pre-Islamic periods as the focus of their writing was on contemporaneous developments.

However, the aforementioned historians and all the authors, who are classified in this category, represent only one dimension of Iranian historiography of Islamic times. A totally different approach and literature have been illustrated by Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh (Book of Kings). Abu ‘l Qasem Ferdowsi (940-1025) was not the first to compose an epic in order to standardize in mythical terms and legendary concepts the pre-Islamic Iranian past; but he was the most successful and the most illustrious. That is why many other epic poets followed his example, notably the Azeri Nizami Ganjavi (1141-1209) and the Turkic Indian Amir Khusraw (1253-1325).

Within the context of this poetical historiography, historical emperors of pre-Islamic Iran appear as legendary figures only to be then viewed as materialization of divine patterns. The origin of this transcendental historiography seems to be retraced in the Sassanid times, but all the major themes are clearly of Zoroastrian identity and can therefore be attributed to the Achaemenid world perception and world conceptualization.

It is essential at this point to state that, until the imposition of modern Western colonial academic and educational standards in Iran, Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh and the corpus of Iranian legendary historiography was the backbone of the Iranian cultural, intellectual and educational identity.

It is a matter of academic debate whether an original text named Khwaday-Namag, written during the Sassanid times, and now lost, is at the very origin of Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh and of the Iranian legendary historiography. The 19th c. German Orientalist Theodor Nöldeke is credited with this theory that has not yet been proved.

All the same, the spiritual standards of this approach are detected in the Achaemenid times.

5- Foreign historiography

Ancient Greek (in reality, Ionian and Attic), Ancient Hebrew and Latin sources of Achaemenid History exist, but first they are external, second they appear to be posterior in their largest part, and third they often bear witness to astounding inaccuracies, fables, untrustworthy data, misplaced focus, excessive verbosity without real substance, and -above all- an enormous and irreconcilable misunderstanding of the Iranian Achaemenid reality, values, world view, mindset, and behavior.

The Ancient Hebrew sources shed light on issues that were apparently critical to the tiny and unimportant, Jewish minority of the Achaemenid Empire; however, these Biblical narratives concern facts that were absolutely insignificant to the imperial authorities of Parsa. One critical issue is concealed by modern scholars though; although all the nations of the Empire were regularly mentioned in the Achaemenid inscriptions and depicted on bas reliefs, the Jews were not. This undeniable fact irrevocably conditions the supposed ‘importance’ of Biblical texts like Ezra, Esther, Nehemiah, etc. All the same, these foreign historical sources are important for the Jews.

The Ionian and Attic accounts of events that were composed by the Carian renegade Herodotus, the Dorian Ctesias, and the Athenian Xenophon present an even more serious problem. They happened to be for many centuries (16th – 19th c.) the bulk of the historical documentation that Western European academics had access to as regards Achaemenid Iran. This situation produced grave biases among Western academics, because they took all these sources at face value since they had no access to original documentation. The grave trouble persisted even after the decipherment of the Old Achaemenid cuneiform writing and the archaeological excavations that brought to daylight original Iranian imperial documentation.

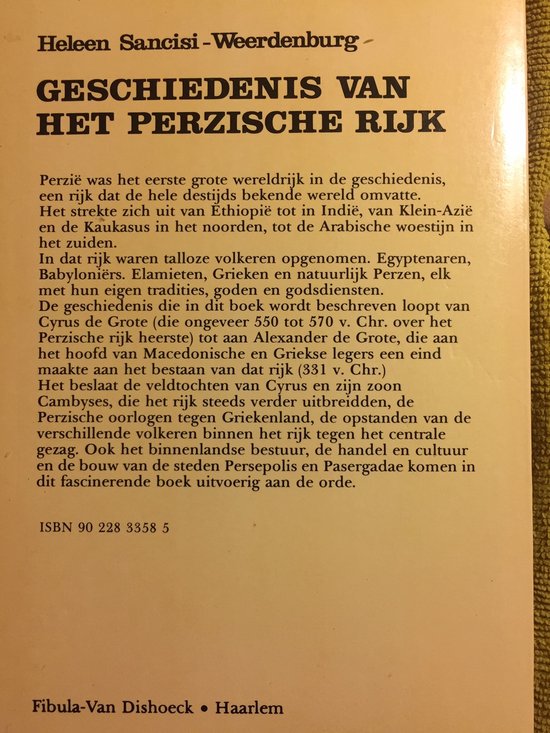

Only recently, at the end of the 20th c., leading Iranologists like Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg started criticizing the absolutely delusional History of Achaemenid Iran that modern Western scholars were producing without even understanding it by foolishly accepting Ancient Ionian myths, lies and propaganda against the Iranian Empire at face value. This grave problem had also two other parameters:

– first, there was an enormous gap of civilization and a tremendous cultural difference between the Iranian imperial world view, the spiritual valorization of the human being, and the Zoroastrian monotheism from one side and the chaotic, disorderly and profane elements of the western periphery of the Empire. The so-called Greek tribes in Western Anatolia and in the South Balkans were not only multi-divided and plunged in permanent conflict; they were also extremely verbose on common issues, they desecrated the divine world with their nonsensical myths and puerile narratives, and they defiled human spirituality with their love stories about their pseudo-gods. But, very arbitrarily and quite disastrously, the so-called Ancient Greek civilization had been erroneously taken as ‘classics’ by modern Europeans at a time they had no access to Ancient Oriental sources.

– second, the vertical differentiation between Imperial Iran as the blessed land of divine mission and the disunited and peripheral lands of conflict, discord and strife that were inhabited by the Greek tribes was reflected on the respective, impressively different types of historiography; to the Iranians, few words written by anonymous scribes were enough to describe the groundbreaking deeds of divinely appointed rulers. But for the Greeks, the useless rumors, the capricious hearsay, the intentional lie, the nefarious expression of their complex of inferiority, the vicious slander, and the deliberate ignominy ‘had’ to be recorded and written down.

The fact that Herodotus’ and Xenophon’s long narratives have long been taken as the basic source of information about Achaemenid Iran demonstrates how disoriented and misplaced modern Western scholarship is. But by preferring to rely mainly on the Ancient Greek lengthy and false narratives, and not on the succinct, true and chaste Old Achaemenid Iranian inscriptions, they totally misrepresent Ancient Iranian History, preposterously extrapolating later and corrupt standards to earlier and superior civilizations.

And whereas Ancient Roman authors, who wrote in Latin (Pliny the Elder, Seneca the Younger, etc.), and Jewish or Christian historians, who wrote in Alexandrine Koine, like Flavius Josephus and Eusebius of Caesarea Maritima, reproduced the style of lengthy narratives that turns History to mere gossip, the great Babylonian scholar Berossus was very reluctant to add personal comments to his original sources or to allow subjective considerations and thoughts to contaminate his text.

In any case, the vast issue of the multilayered damages caused by the untrustworthy Ancient Greek historiography to modern Western academics’ perception and interpretation of Achaemenid Iran is a topic that deserves an entirely independent seminar.

————–

To watch the video (with more than 110 pictures and maps), click the links below:

HISTORY OF ACHAEMENID IRAN – Achaemenid beginnings 1Α

By Prof. Muhammad Shamsaddin Megalommatis

https://vk.com/video429864789_456239757

https://ok.ru/video/5416043547224

https://www.brighteon.com/ca749192-7c1b-4a9d-901d-5f530611c965

————————

To listen to the audio, clink the links below:

HISTORY OF ACHAEMENID IRAN – Achaemenid beginnings 1 (a+b)

https://vk.com/megalommatis?w=wall429864789_8990%2Fall

https://megalommatis.podbean.com/e/history-of-achaemenid-iran-1a-course-i-achaemenid-beginnings-1a/

——————————

Download the course in PDF: