Pre-publication of chapter XXVI of my forthcoming book “Turkey is Iran and Iran is Turkey – 2500 Years of indivisible Turanian – Iranian Civilization distorted and estranged by Anglo-French Orientalists”; chapters XXIV, XXV and XXVI constitute the Part Ten {Fallacies about the Times of Turanian (Mongolian) Supremacy in terms of Sciences, Arts, Letters, Spirituality and Imperial Universalism} of the book, which is made of 12 parts and 33 chapters. Until now, 9 chapters have been uploaded as partly pre-publication of the book; the present chapter is therefore the 10th (out of 33). A list of the already pre-published chapters (with the related links) is made available at the end of this chapter.

———————————

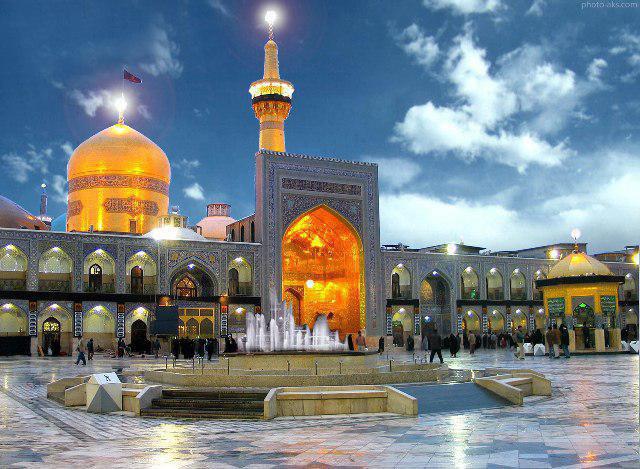

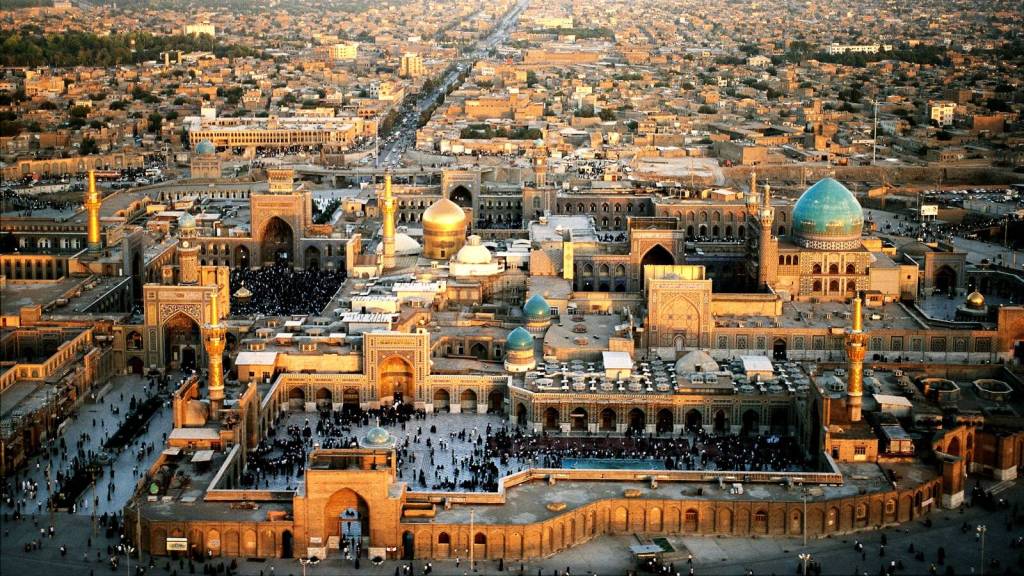

Imam Reza Mosque, Mashhad – NE Iran

Timur was not a monstrous murderer as the Western historiographers depicted him in their vicious and pernicious, and therefore absolutely worthless and totally untrustworthy, narratives. Historical texts written by Western European authors about Timur reflect only the impotency of the hypocritical, sacrilegious, pseudo-Christian, petty kings of Europe. Like Genghis Khan, Timur shared the traditional Eastern Turanian vision of Tengrist Universalism; sectarian, ethnic, and other divisions or divisive lines were meaningless, barbarian, and inhuman to him. As per his worldview, these divisions represented only the interference of Evil in the human world. Contrarily to most of the then world’s kings and to all of today’s criminal politicians and statesmen, Timur did not engage in battles and wars for his personal, tribal, ethnic or national material benefit, but for the overall, true progress of the faithful Mankind.

Beyond being a grandmaster in chess, Timur was a great mystic, a knowledgeable interlocutor, and an emperor who highly evaluated erudition, literature, philosophy, arts, architecture and sciences. If today people get confused about Timur’s religious views, this is not due to an eventual misinterpretation of historical sources, but to the present confusion between spirituality and religion. It is enough for someone to associate spirituality with religion in order to totally misperceive entire historical eras. Consequently, Western scholars have nowadays difficulty to define whether Timur was a Sunni or a Shia; this is only normal, because there are no Sunni or Shia. This forged division cannot apply in Timur’s life. In fact, like every spiritually alive man, Timur was a secular monarch. Historically, he continued the tradition of Harun al-Rashid’s Abbasid Caliphate, the practices of the Seljuk sultans, and the modus operandi of the Ilkhanate: his empire was an absolutely secular state.

Today, the term ‘secular state’ is confused with the paranoia of the post-WW II world, but in reality the ‘secular state’ has nothing to do with atheism, agnosticism, academic elitism, sacrilegious intellectualism, rationalism, materialism, hedonism, pan-sexism, and all the evil modern bogus-concepts (politics, democracy, multi-partite system, human rights, etc.), which have been associated with the supposedly ‘secular’ societies of today’s decayed and putrefied Western world. In honorable distinction from, and in total contrast with, other modern states, Kemal Ataturk’s Turkey (more specifically, the 1923 Constitution and the period until 1938) had nothing to do with today’s pseudo-secular Western societies, which in reality are strictly religious, yet scrupulously masqueraded, states with Satanism as secretively and tyrannically imposed dogma.

In Timur’s empire, there was sheer distinction between spirituality and religion, and every person was allowed to believe the religious dogma that he chose; religious authorities of all doctrines had the freedom to perform the rites and fulfill the cults of their faith; and there was no interference of the imperial administration in these activities. Many Western scholars attempted to tarnish Timur’s fame by holding him responsible for the gradual decline of Nestorian Christianity, Buddhism and Manichaeism in Central Asia, Siberia and Mongolia; that is totally misplaced.

Neither Genghis Khan nor Timur were ‘personally’ responsible for this fact. Timur did not tolerate any sectarian act of violence and discrimination. The reasons for which these three religions disappeared in the aforementioned regions have nothing to do with imperial decisions of any sort; they are totally unrelated to the Genghisid and Timurid empires. As a matter of fact, Buddhism was already present in the eastern provinces of Achaemenid Iran. Manichaeism and Nestorian Christianity appeared during the Sassanid times.

These three religions had followers among several nations that lived across the Iranian plateau, Central Asia, and the mountainous ranges between China, Indus River valley, and parts of Siberia (Aramaeans, Eastern Iranians, Sogdians, Turanians, Khotanese, etc.). However, the process of their disappearance was complex, gradual and slow, covering ca. 700 years (750-1450); first, the Islamic advance towards Central Asia and the Indus River valley (middle 7th c. to middle 8th c. CE) was detrimental to some nations, notably the Sogdians, who were terribly decimated.

Second, the proliferation of mystical orders, spiritual systems, dissident movements, eschatological-messianic concepts, theological schools, soteriological groups, and literary-poetical reassessments of the historical, pre-Islamic past produced an abundance of attractive alternatives for all the nations of the aforementioned diverse regions (over the period between the 8th c. and the 11th c.).

Third and more important, the overwhelming migrations that took place across Asia between the 11th c. and the 15th c. totally changed the landscape between Central Europe and Eastern Siberia; the newly arrived nomads usually accepted concepts of Islam that suited best their traditions of Tengrism and Shamanism. Then, Nestorians, Buddhists and Manichaeans proceeded to the East (i.e. China), since it was well known that settled communities of their coreligionists existed there too and they lived in peace.

Timur met many leading mystics, scholars, scientists, theologians, architects and poets of his times; his meeting with Hafez (Khwaja Shams-ud-Din Muhammad; 1315-1390), the great Iranian poet from Shiraz, was commemorated for centuries among Islamic rulers and erudite scholars, because their conversation bears witness to Timur’s ostensible ability to appreciate wit, intellect, self-sarcasm, and modesty.

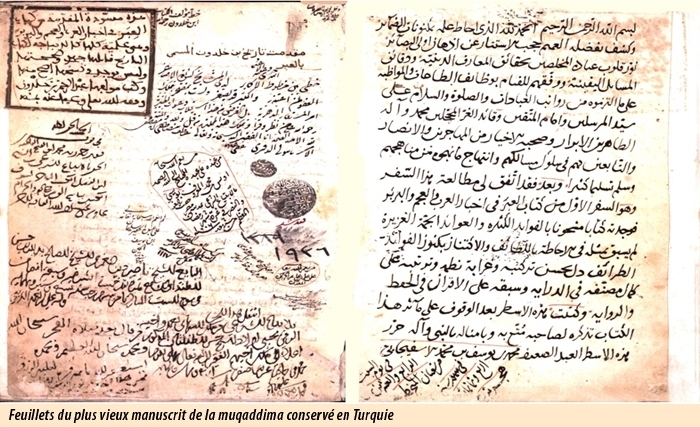

Manuscript miniature depicting the encounter between Timur and Ibn Khaldun

Two pages from a manuscript of Ibn Khaldun’s al Muqaddimah

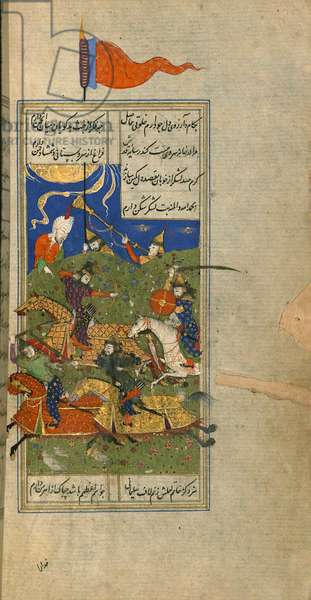

16th c. copy of Hafez’s Divan with fighting scene

Ceiling decoration of the tomb of Hafez in Shiraz

Hafez’s Mausoleum, Shiraz

Timur met Ahmad ibn Arabshah (1389-1450) during the siege of Damascus; he saved him (along with many other scholars) and then sent him to Samarqand; later, the Damascene author returned to Damascus and proceeded to Edirne / Adrianople, the Ottoman capital at the time; there he composed a voluminous historical description of Timur’s deeds and conquests (Aja’ib al-Maqdur fi Nawa’ib al-Taymur: The Wonders of Destiny of the Ravages of Timur).

One can however instantly understand why Ahmad ibn Arabshah presented a negative image of Timur, who had saved his life: writing while you are at the Ottoman payroll can never be a guarantee for objective description and impartial narrative. Had Ahmad ibn Arabshah written a true and unbiased ‘Tarikh’, the Ottoman sectarian theologians and the rancorous courtiers of Mehmed I and of Murat II would have burned the manuscripts. The Ottoman hatred of Timur and the Timurids lasted until the demise of the Caliphate – only to the detriment of the Ottoman family.

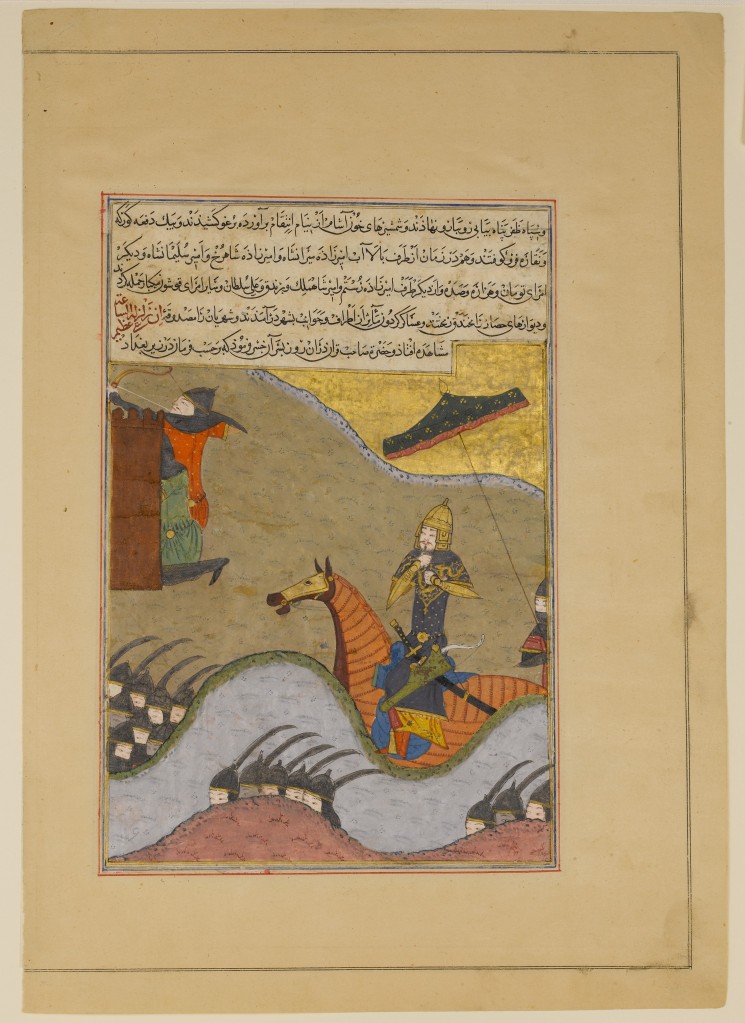

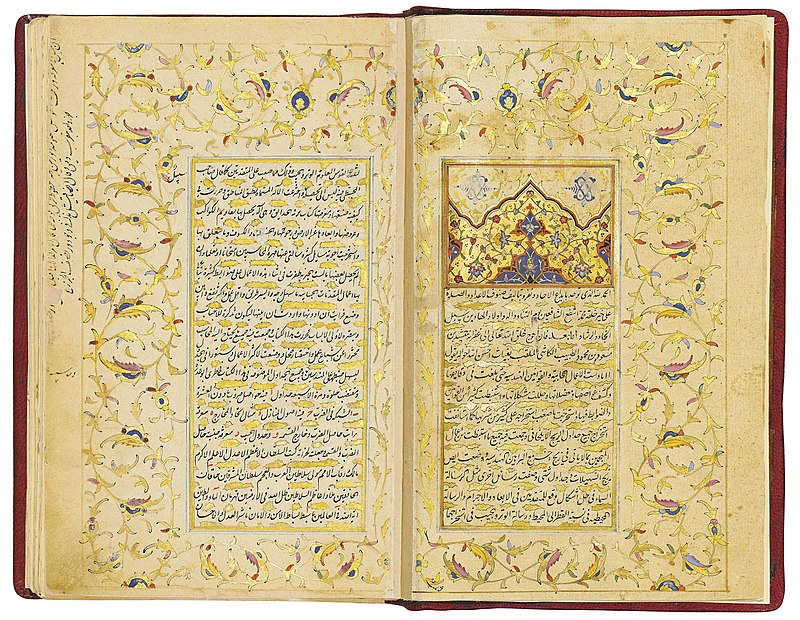

The major and most trustworthy historical biographies and sources for the life, the conquests, and the deeds of Timur are Nizam ad-Din Shami’s Zafar nameh (ظفرنامه, Book of Victory), Sharif al-Din Ali Yazdi’s Zafar nameh, and Abu Taleb Husayni’s Malfuzat-e Timuri and the associated appendix Tuzokat (which is basically the Persian translation of an earlier manuscript written in Chagatai Turkic and found in Yemen; Abu Taleb Husayni presented his work to the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan in 1637).

The conquest of Baghdad by Timur depicted on the miniature of a manuscript of in Sharif al-Din Ali Yazdi’s Zafar nameh

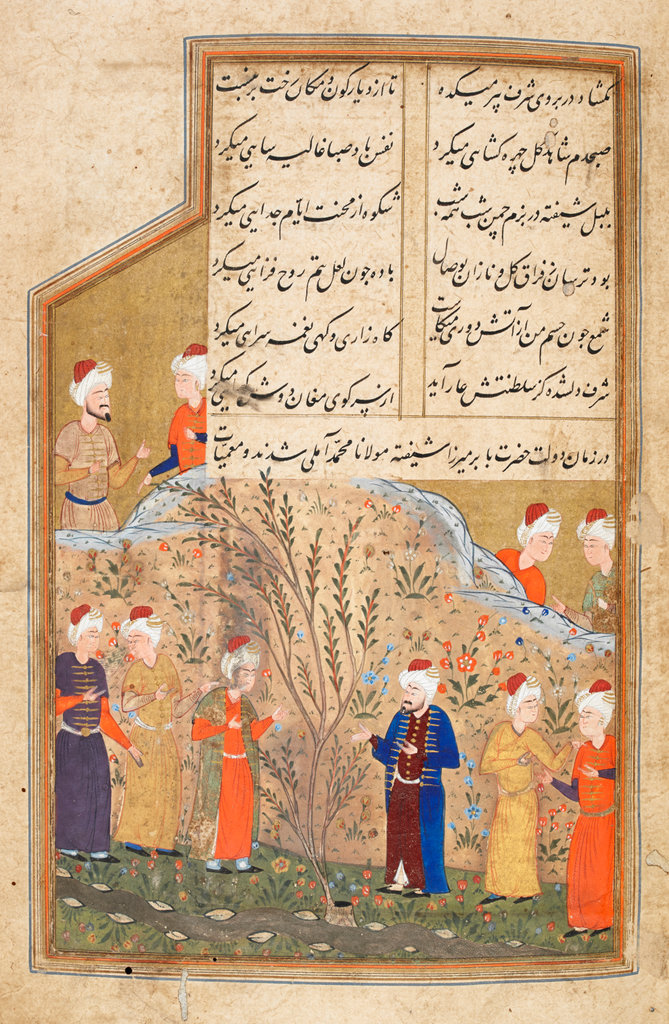

Sharaf al-Din Ali Yazdi with Muhammad Amuli; folio from the Majalis al-Ushaq of Kamal al-Din Gazurgahi, which was written and decorated in Shiraz around 1560

The phenomenon that Western scholars describe as Timurid ‘Renaissance’ consists in a serious misperception of the entire historical period; the irrelevant terminology was invented to project Western concepts onto the Islamic world. In general, the term ‘Renaissance’ cannot apply either in the case where there is uninterrupted continuity or in the manifestation of newly invented concepts, ideas, forms, styles or rhythms. Truly, the 2nd half of the 14th century and the entire 15th century were a period of fully-fledged spiritual, academic, scientific, literary, artistic, architectural, cultural, intellectual, and artisan creativity and dynamism across almost all Islamic lands.

However, this phenomenon does not have any trait of revival or rebirth of an earlier experience or condition. Quite contrarily, it consists in the culmination of the Islamic genius as manifested since the days of Abbasid Baghdad, Bayt al-Hikmah, Ferdowsi, Nizam al Mulk, and Nasir el-Din al Tusi. One may eventually express a rhetorical question like the following in order to fully demonstrate the inaccuracy of the Western neologism Timurid ‘Renaissance’:

– What was interrupted, terminated, dispersed, lost or forgotten as Islamic science, art, scholarship and craftsmanship in the days of Nasir al-Din al Tusi (1201-1274), only to restart, resume, and be rediscovered, revived and reborn at the time of Timur?

The answer is very simple: nothing!

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi’s works, explorations, studies, and astronomical tables and catalogues were continued in the works of Jamshid al-Kashi, Qadi Zadeh al Rumi (of Eastern Roman origin), and Ulugh Beg, Timur’s grandson, third successor, and astronomer emperor. There is an undisputed continuity from the Observatory of Maragheh to the Observatory of Samarqand, pretty much like there is an absolute continuity in Islamic science, academic life, and artistic creativity from Abbasid Baghdad to Timurid Samarqand.

Imam Reza shrine in Mashhad

Aerial view of Imam Reza shrine in 1976

The tomb of Imam Reza

And there was novelty! Timurid architecture, as manifested in Samarqand, Herat, Balkh, Turkistan {Kazakhstan; the Mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yasawi (1093-1166) which was commissioned by Timur himself}, Mashhad (Goharshad Mosque, built in honor of Empress Goharshad, Shah Rukh’s royal consort), and elsewhere, may have several traits that date back to Seljuk times, and may well represent the next stage of evolution from Ilkhanate architecture. However, in reality, Timurid architecture consists in an entirely different and totally new Islamic style of architecture. With their characteristically elevated, fluted domes, with their deep niches, with their impressively raised iwans (vaulted gateways), with their very typical shabestans (underground spaces), with their innovative muqarnas (also known as honeycomb vaulting), and with their inscriptions on mosaic tiles, all the Timurid mosques, madrasas and mausoleums are unique of style and known for their rule of axial symmetry.

Goharshad Mosque, Mashhad

Goharshad tomb, Herat

High place of Timurid architecture is by definition the Registan esplanade at Samarqand, a vast public square with three astoundingly monumental universities; ‘madrasa’ at the time did not mean only ‘theological school’, because theology was only one of the numerous -more than 20- academic topics taught in the madrasas. The first madrasa built in Registan was the Ulugh Beg Madrasah (construction: 1417–1420); two centuries later, the Sher-Dor Madrasah (1619–1636) and the Tilya-Kori Madrasah (1646–1660) were built at the times of the Janid dynasty (established by descendants of the Khanate of Astrakhan) in exactly the same architectural style. Subsequently, Timurid architecture influenced architectural styles in the Mughal, Safavid and Ottoman empires.

Registan Square, Samarqand

Ulugh Beg Madrasah: one of the three masterpieces of Timurid Architecture in Registan

Sher-Dor Madrasah, Registan

Tilya Kori Madrasah, Registan

Many irrelevant European scholars characterized the Turanian Timurid architecture as “Persian style”, but there is nothing ‘Persian’ in it. The enormous iwans may certainly be a reminiscence of the Parthian iwans, but Parthia was not ‘Persia’; quite contrarily, the Arsacid Empire of the Parthians was called ‘Iran’ and the Parthians were not ‘Persians’ but Turanians. Similar cases bear witness to the numerous colonial discriminatory abuses and to the academic, Indo-Europeanist racism.

Bibi-Khanym Mosque, Samarqand; it was built in 1399 by the Tamerlane’s favorite wife, Bibi-Khanym, in honor of his return from the war in India

Timur and Shah Rukh patronized the arts, improving the traditional Art of the Book, sponsoring scholars, scientists and artists, and demanding exquisite illustrations of manuscripts (miniatures). Manuscript illumination became then a highly revered art and several schools (styles) were distinguished in this regard; elements of Turanian, Central Asiatic, Iranian, and Chinese artistic traditions were then blended into a new style. The Timurids in general were remembered as benefactors of scholars, poets, artists, artisans, and architects. About:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timurid_Renaissance

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hafez

https://www.academia.edu/17427522/A_Note_on_the_Life_and_Works_of_Ibn_Arabshah

https://iranicaonline.org/articles/historiography-v

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zafarnama_(Shami_biography)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sharaf_ad-Din_Ali_Yazdi

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zafarnama_(Yazdi_biography)

https://iranicaonline.org/articles/abo-taleb-hosaym-arizi

https://www.academia.edu/2256806/The_Histories_of_Sharaf_al_Din_Ali_Yazdi_A_Formal_Analysis

https://iranicaonline.org/articles/kasi

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jamsh%C4%ABd_al-K%C4%81sh%C4%AB

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Q%C4%81%E1%B8%8D%C4%AB_Z%C4%81da_al-R%C5%ABm%C4%AB

https://www.maa.org/press/periodicals/convergence/mathematical-treasures-qadi-zada-al-rumis-geometry

https://www.academia.edu/398260/Timurid_Architecture_In_Samarkand

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mausoleum_of_Khoja_Ahmed_Yasawi

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Goharshad_Mosque

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muqarnas

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iwan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Registan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Persian_domes

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gur-e-Amir

Forensic facial reconstruction: Shah Rukh

Gur-i Emir Mausoleum, Samarqand, Shah Rukh’s headstone 3rd from the left

Tanka (silvr coin) of Shahrukh Mirza (Yazd mint)

Shah Rukh’s reign (1409-1447) is considered as the Golden Era of the Timurid Empire. He ruled over the largest part of Timur’s territory and only after his nephew Khalil Sultan (1405-1409) proved to be totally unable to reign. Timur’s western territories were lost because of the chaos caused by the conflicts between the Karakoyunlu and the Akkoyunlu and following the Karakoyunlu victory over Miran Shah and the Timurid army (1408). Shah Rukh preferred to rule in peace with his neighbors and this helped the scholarly, artistic, artisan and architectural activities that burgeoned in his empire. Shah Rukh created a solid base in Herat (today’s NW Afghanistan) where many Genghisid relatives of his royal consort Goharshad lived, as they were the local administrators.

Goharshad ranked below Shah Rukh’s other Genghisid wife, Malekat Aga. However, due to her family support, to her inclination for letters, arts and public works, and because of her sense of human relations, she became a considerable factor of her imperial husband’s success. As a matter of fact, Goharshad was the daughter of a notable Genghisid prince Giath al-Din Tarkan whose honorary title (Tarkan) was initially bestowed by Genghis Khan himself upon one of his ancestors. It is therefore only normal that, after Shah Rukh invaded Samarqand and was accepted as the final successor to his father by all, he transferred the imperial capital to Herat, leaving his son Ulugh Beg as governor of Samarqand.

Herat had been destroyed by Genghis Khan (1221) but rebuilt during the Ilkhanate; however, the magnificent edifices and architectural monuments erected there at the time of Shah Rukh and Goharshad made of the city one of the Islamic world’s most splendid capitals. The erection of the Musallah complex of Herat (1417), which involved mausoleums, madrasa, mosque and five minarets, is the most important among the many monuments patronized by Shah Rukh’s royal consort. The famous shrine of Gazur Gah (an 11th c. mystic who lived in Herat and is historically known as Khwaja Abd Allah) was also built (1425) under the imperial patronage of the Timurids. And the same is valid for Goharshad Mausoleum that was built (1438) as the tomb of Shah Rukh’s and Goharshad’s son, prince Baysunghur.

Perhaps the most impressive and most colorful monument commissioned by the imperial couple was the enormous Goharshad Mosque built in Mashhad (today’s NE Iran). With a 43 m high dome, with two 43 m high minarets, and with four iwans, the mosque was always considered as one of the most impressive and most beautiful monuments of Islamic architecture worldwide.

Patron of authors, explorers and erudite scholars, Shah Rukh benefitted from the great talent of Hafez Abru, who had first been one of Timur’s most favorite scholars and authors. Abdallah ben Lutfallah (as is the full name of Hafez Abru) accompanied Timur in several military campaigns and was present in all the imperial court feasts and symposia convened by Timur. After the death of the conqueror, he entered the service of Shah Rukh, who commissioned the elaboration of numerous historical and geographical opuses, notably

i. Dayl-e Zafar nameh ye-Shami (continuation of Nizam al-Din Shami’s biography of Timur for the period 1404-1405)

ii. Dayl-e Jame’ al-Tawarih (continuation of Rashid al-Din’s Universal History by an anonymous author who covered the period 1304-1335)

iii. Tarih-e Shah Rukh (History of the reign of Timur’s son until 1414; this text was later incorporated in other historical compilations by Hafez Abru)

iv. Tarih-e Hafez Abru, which is a Universal History and Geography commissioned by Shah Rukh in 1414 (originally it was scheduled to be the Farsi translation of selected geographical treatises earlier written in Arabic, but finally it became an original opus of historical geography); it also involved a map (British Library manuscript Ms. 1577) designed after the methods of the historical Balkh School of Cartography.

v. Majmu’a-ye Hafez-e Abru, i.e. a Universal History commissioned by Shah Rukh in 1418 in order to incorporate Bal’ami’s translation of Tabari’s Tarih to Farsi and Rashid al-Din’s Universal History, which was extended by Hafez Abru until 1393.

vi. Majma’ al Tawarih al Soltani, a Universal History until 1426, written for Shah Rukh’s son Baysunghur.

Shah Rukh established good diplomatic relations with Ming China by sending an imperial delegation to Beijing in 1419-1422. Member of the delegation was Ghiyath al-Din Naqqash, who was tasked to compose the official diary, which was not saved independently down to our times, but was largely incorporated in other historical opuses. As an official account, this text was highly evaluated and therefore translated to various Turkic languages in later periods. The Timurid delegation was received with imperial honor, traditional pomp, and great joy at the Ming court. Shah Rukh created an environment of stability and peace across Asia, systematically exchanging embassies and establishing good relations also with the Sultanate of Delhi (notably Khizr Khan), the Bengal Sultanate (and particularly with Shamsuddin Ahmad Shah), the Akkoyunlu, the Ottomans, the Turanian Ormuz kingdom in the Hormuz straits (then under Bahman Shah II), and even the Mamluks of Egypt.

As the Dravidian ruler (Samoothiri) of Calicut (in the presently occupied Deccan, in South ‘India’) encountered several Timurid officials who, while returning from the Sultanate of Bengal, anchored in his harbor, he decided to send an embassy to Herat. A Farsi-speaking Dravidian Muslim led the official delegation and impressed Shah Rukh, who subsequently dispatched a Timurid delegation to Calicut (Kozhikode; 1442-1443) under Abd al-Razzsaq Samarqandi (1413–1482); the scholar-diplomat wrote an extensive report of his mission that he later incorporated in his chronicle Maṭla’-e sa’dayn va maǰma’-e baḥrayn (the rise of the two auspicious constellations and the junction of the two seas). He thus offered insight into first, the small kingdom of Calicut and the local rulers (named Saamoothiri) and second, the Dravidian Vijayanagara kingdom, because the local king Deva Raya II invited Abd al-Razzsaq Samarqandi to his court.

Shah Rukh had however to fight several battles against the Karakoyunlu (in 1420, 1429 and 1434) and the Timurid army was victorious every time. However, since Shah Rukh did not inherit the brutality of his father, his victories did not solve the problem of the constantly rebellious Turkmen and the unstable situation in the western confines of the Iranian plateau, North Mesopotamia, South Caucasus and Eastern Anatolia continued during most of the 15th c. until the Akkoyunlu managed to achieve a decisive victory (1467) over the Karakoyunlu only to be later supplanted by the Safavid Empire (1501).

After Timur crushed the Hurufi rebellion in 1394, the secret Kabbalistic sect launched a subversive campaign of anti-Timurid hatred and evidently conspired against the empire by placing in the Timurid court several secret members who would be later mobilized against the imperial administration. In 1426, Shah Rukh risked his life in an assassination attempt; he survived and then undertook a great effort to uproot the evil secretive sect that promoted black magic practices by attributing numerical values to letters of the alphabet and then evoking spiritual potentates. Several modern scholars, who happen to be Kabbalists and Satanists, tried therefore to tarnish the fair name of Shah Rukh and to distort the truth by accusing him of ‘anti-intellectualism’, a nonexistent term coined by evil and inhuman gangsters in order to denigrate everyone who makes it impossible for them to conduct their perverse and evil operations. This is pathetic and ludicrous; the historical truth is that Shah Rukh was the patron of artists, scholars, erudite authors and architects. And in any case, an ‘intellectual’, who gets initiated in the secrets of a Kabbalist sect, already ceases to be a human.

When Shah Rukh died at the age of 70 (1447), his firstborn son Ulugh Beg (then at the age of 53; 1394-1449) succeeded him; he was also Goharshad’s favorite son and he had acquired a remarkable experience in travels, scholarly explorations, and imperial administration. He had been the governor of Samarqand and the entire Transoxiana (Mawarannahr) since 1409 (when he was just 15). And since the early 1420s, he was an accomplished scholar, mathematician and astronomer with his own madrasa and his own observatory – the best of his time. About:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shah_Rukh

https://iranicaonline.org/articles/gowhar-sad-aga

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6504717/

https://iranicaonline.org/articles/hafez-e-abru

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hafiz-i_Abru

https://pieterderideaux.jimdofree.com/7-contents-1401-1450/hafiz-i-abru-1420/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Musalla_Complex

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Musalla_Minarets_of_Herat

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shrine_of_Khwaja_Abd_Allah

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gawhar_Shad_Mausoleum

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Goharshad_Mosque

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghiy%C4%81th_al-d%C4%ABn_Naqq%C4%81sh

https://iranicaonline.org/articles/abd-al-razzaq-samarqandi-historian-and-scholar-1413-82

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abd-al-Razz%C4%81q_Samarqand%C4%AB

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zamorin_of_Calicut

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vijayanagara_Empire

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deva_Raya_II

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ormus

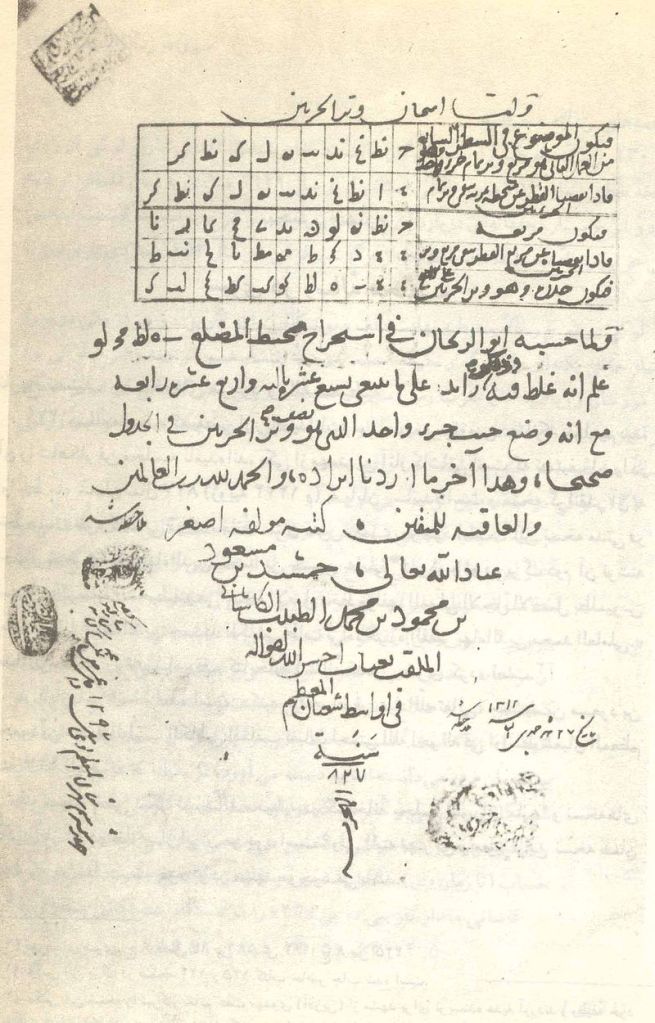

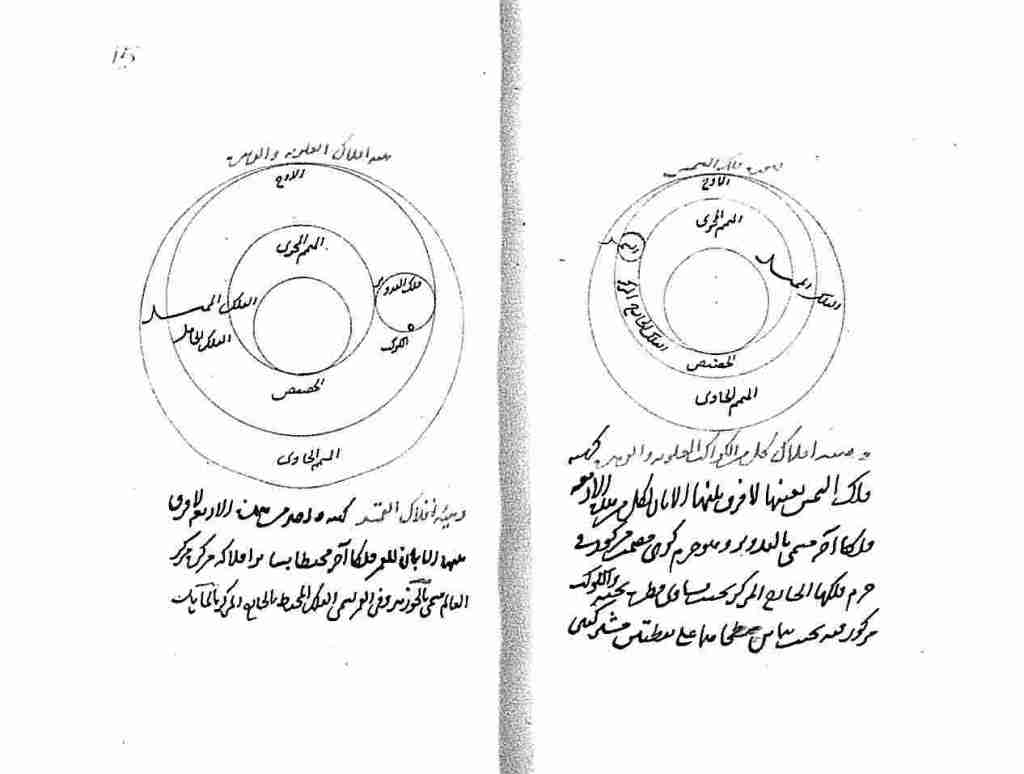

Mirza Muhammad Taraghay bin Shahrukh (mainly known as Ulugh Beg, i.e. ‘the great ruler’; 1394-1449) was the unique case of Turanian Muslim Emperor who was also a consummate scholar, a leading mathematician, and the then world’s foremost astronomer. He ruled for only two years and only after having delivered pioneering opuses, notably Zij-i Sultani (زیجِ سلطانی; the astronomical tables of the Sultan, i.e. of himself), which is a collective work of many leading astronomers working under his guidance to produce a list of no less than 1018 stars.

Ulugh Beg was an exceptional man in every sense; he had 13 wives, he spoke ca. 10 languages (Chagatai Turkic, Farsi, Arabic, Syriac Aramaic, Chinese, and several other Western and Eastern Turanian languages), and he seems to have been a prodigious young man, very knowledgeable since his adolescence; and thanks to his numerous travels, he saw great monuments, universities, libraries and centers of learning that impressed him. However, Nasir el-Din Tusi’s observatory in Maragheh seems to have impacted the young imperial traveler more than any other edifice, and this was the reason for which, after he was appointed governor of Samarqand by his father Shah Rukh in 2009, he started to turn the city into the world’s leading academic center.

Ulugh Beg, as depicted by an anonymous painter of the period 1425-50

Ulugh Beg coin; AH 852 (1448-9) Herat mint

Samarqand Observatory, constructed by Ulugh Beg in the 1420s and rediscovered by Russians archaeologists in 1908

Ulugh Beg Observatory; the trench accommodated the lower section of the meridian arc.

Mirzo Ulughbek and Ali Kushchi working in the Samarqand Observatory, as per the imagination of modern local artists

Ulugh Beg created therefore an inviting environment for scholars from various regions and countries, and that’s why many researchers, explorers, scientists and students gathered in Samarqand as early as the 1420s. Ulugh Beg Madrasa was built in the period 1417-1420, and its parts were decorated with tiles of blue, light blue and white colors that all have a great symbolism in Turanian Tengrism. Two years later, the Ulugh Beg Observatory was constructed, as we can deduce from the letters sent by Jamshid al Kashi to his own father; these valuable documents were recently (in the 1990s) found, published and translated. Jamshid al Kashi (1380-1429) was a leading astronomer who worked with Ulugh Beg in Samarqand’s imperial observatory.

Another leading scholar, who contributed to the academic works, scholarly studies, and astronomical tables and catalogues undertaken in the observatory, was Ali Qushji (1403-1474; full name: Ala al-Dīn Ali ibn Muhammad). Ali Qushji was not greatly important only because he participated in the elaboration of the Zij-i Sultani and he made many other contributions to sciences, writing numerous astronomical, mathematical, mechanical, linguistic, philological and theological treatises; he is also credited for having established a real bridge between Samarqand and Istanbul in terms of scientific-academic life, scholarly exploration, and intellectual endeavors.

As a matter of fact, Ali Qushji was one of the very few scholars of his times to have met personally with three powerful emperors, namely the Timurid Ulugh Beg, the Akkoyunlu Uzun Hasan (1423-1478), and the Ottoman Mehmed II (also known as Fatih; 1432-1481). Ali Qushji delivered personally a copy of Zij-i Sultani to Mehmed II, evidently making the Ottoman sultan envy the unequaled superiority of the great Timurid capital Samarqand in terms of science, exploration, scholarship and intellect.

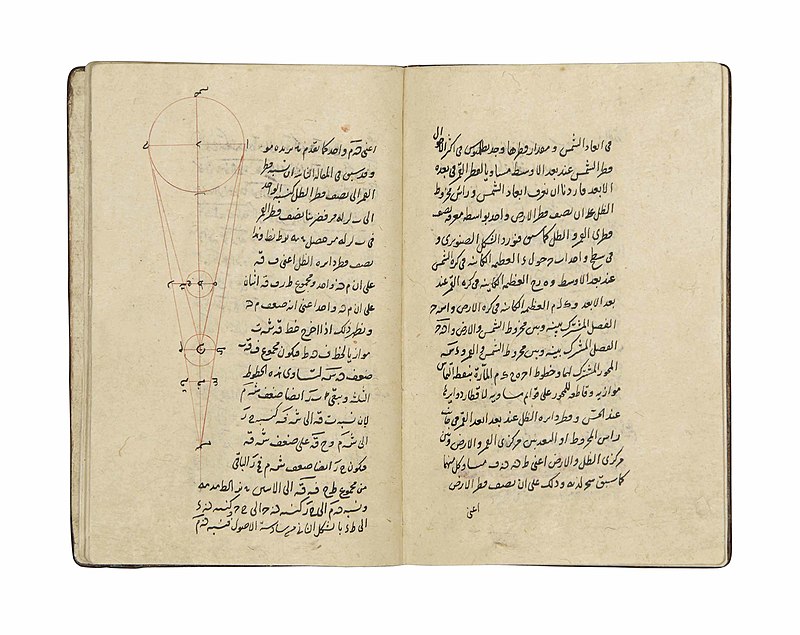

Jamshid al Kashi: opening bifolio of his major opus Miftah al-Hisab

Two pages from a manuscript of Jamshid al Kashi’s Sullam al-sama’

Jamshid al-Kashi’s The Key to Arithmetic; the last page of the manuscript

Pages of a manuscript with treatises elaborated by Ali al Qushji

Other remarkable scholars, who formed Ulugh Beg’s team, were Mu’in al-Din al-Kashi and Qadi Zadeh al-Rumi (1364-1436), a leading mathematician and astronomer of Eastern Roman descent, tutor and mentor of Ulugh Beg; Qadi Zadeh was greatly renowned for his pertinent commentaries on the works of earlier Turanian Islamic astronomers, like al-Jaghmini (full name: Mahmud ibn Muhammad ibn Umar al-Jaghmini; 13th – 14th c.), Shams al-Din al-Samarqandi (ca. 1250 – ca. 1310), and Nasir ad-Din al-Tusi. Students from Anatolia, Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Indus River valley, the Ganges River valley, China and parts of Siberia were flocking to Samarqand to benefit from this worldwide unique environment.

To these great scholars it took no less than 15 years to compose in Farsi the voluminous Zij-i Sultani (completed in 1437), which was the World History’s most accurate and most complete astronomical table and star catalogue up to its time. Zij is an Islamic astronomical book that presents in tabular form various parameters used for astronomical calculations of the positions of stars therein included; as it can be assumed, it takes a great deal of observation in order to establish this type of documentation.

Around 20 different Zij catalogues have been established during the Islamic times, either saved until our times or not. However, Zij-i Sultani surpasses in terms of scholarship all earlier astronomical tables, including the 2nd c. CE Ancient Egyptian astronomer Ptolemy’s Almagest (Μαθηματικὴ Σύνταξις – Mathematike Syntaxis; المجسطي – al-Majisti). Ulugh Beg’s outstanding masterpiece was later translated to Arabic, Ottoman Turkish, and several European languages.

In 1437, ten years before succeeding his father Shah Rukh on the throne of the Timurid Empire, Ulugh Beg specified the sidereal year as being 365d 6h 10m 8s long, which is an error of +58 s as per today’s calculations. Comparatively, Copernicus in 1525 reduced the margin of the error by 28 seconds, but the 9th c. CE Aramaean Sabian astronomer Thabit ibn Qurra (whose works, translated to Latin, were the primary sources of Copernicus) had determined the length of the sidereal year as 365 days, 6 hours, 9 minutes and 12 seconds (with an error of only 2 seconds as per today’s calculations).

After Shah Rukh’s death, Ulugh Beg had to fight in order to defend his right to succession; he won in the battle at Murghab (بالامرغاب; in today’s Afghanistan/not to be confused with Murgab in Eastern Tajikistan) over his nephew Ala al-Dawla (son of Ulugh Beg’s late brother Baysunghur/ بایسُنغُر) and advanced to Herat; there, in 1448, carried out a terrible massacre of the local population, taking revenge of their support to his nephew and demonstrating his Timurid originality. Ulugh Beg’s reign was brief and unhappy; his son Abd al-Latif Mirza (1420-1450) had an enormous psychological complex of inferiority toward his authoritatively intellectual and exceptionally erudite father, and he rebelled against him. After Abd al-Latif Mirza’s victory in a battle nearby Samarqand, Ulugh Beg had to surrender (1449), but the treacherous and evil son was not pleased with this, and he had his father assassinated, when the deposed Ulugh Beg was proceeding to Hejaz for Hajj.

The patricidal Abd al-Latif Mirza (in Farsi: padarkush; پدر کش) ruled for less than a year, having the support of evil, ignorant and rancorous theologians, who hated Ulugh Beg’s scholarly integrity, intellectual genius, scientific leadership, and secular rule. However, the outright majority of the population hated the ungrateful son for his two repugnant sacrileges; few days after having his father executed, Abd al-Latif Mirza killed also his brother Abd al-Aziz. So, in 1450 the patricidal and fratricidal ruler was murdered, and then came to power Ulugh Beg’s nephew Abdullah Mirza (son of Ibrahim Sultan, who was son of Shah Rukh and also a renowned artist and calligrapher); he rehabilitated his uncle’s imperial tradition and reputation. About:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ulugh_Beg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ulugh_Beg_Observatory

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Astronomy_in_the_medieval_Islamic_world#Observatories

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ulugh_Beg_Madrasa,_Samarkand

lea https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zij-i_Sultani

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zij

http://vlib.iue.it/carrie/texts/carrie_books/paksoy-2/cam6.html

https://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/cities/uz/samarkand/obser.html

https://www.academia.edu/39741365/Bibliography_about_Ulugh_Beg_and_Samarkand_Observatory

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234382647_Ulugh_Beg_Astronom_und_Herrscher_in_Samarkand

http://www.jphogendijk.nl/arabsci/kashi.html

https://www.orientalarchitecture.com/sid/1347/uzbekistan/samarkand/ulugh-beg-madrasa-of-samarkand

https://archnet.org/sites/2123

https://www.wdl.org/en/item/3864/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ali_Qushji

https://iranicaonline.org/articles/astrology-and-astronomy-in-iran-#pt3

Click to access Journal%20for%20the%20History%20of%20Astronomy%20November.pdf

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Кази-заде_ар-Руми

https://islamsci.mcgill.ca/RASI/BEA/Qadizade_al-Rumi_BEA.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Th%C4%81bit_ibn_Qurra

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abdal-Latif_Mirza

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ibrahim_Sultan_(Timurid)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abdullah_Mirza

After Ulugh Beg’s assassination, the Timurid Empire was in reality dissolved. The trends of imperial disintegration, tribal split, intra-family rivalry, and military localism prevailed at a time when Uzbek and Kazakh migrations were upsetting numerous settled populations in Central Asia. The Timurid Empire underwent a real fragmentation before totally disappearing. Abdullah Mirza was not able to rule for more than a year and only in Transoxiana (Mawarannahr); Timurid princes became independent in parts of Khorasan, Fars, and Iraq-e Ajami (Zagros Mountains).

Abu Sa’id Mirza (1424-1469; son of Muhammad Mirza, who was the son of Miran Shah, third son of Timur) was able to rule (1451-1469) and reunify the central parts of his great-grandfather’s empire. He allied with the Uzbeks (notably Abu’l-Khayr Khan: 1428-1468), but he faced many rebellions from Timurid princes of several provinces that he managed to suppress in terrible tribal massacres. He even executed Shah Rukh’s widow, the legendary dowager-empress Goharshad, accusing her of plotting against him by using her great-grandson. He arranged a temporary peace with the Karakoyunlu, but entered into an ill-fated war with the Akkoyunlu (who were former allies of the Timurids) and their powerful king Uzun Hasan. Finally, in February 1469, in the battle of Qarabagh, Abu Sa’id Mirza was defeated and held captive; Uzun Hasan handed him over to his Timurid allies, who remembering his monstrosity toward Goharshad executed him. Finally, Uzun Hasan sent Abu Sa’id Mirza’s decapitated head to the Mamluk ruler of Egypt Qaitbay, who arranged a proper burial.

Various Timurid princes ruled then in Khorasan, Kabul, Balkh, Fergana, Fars, and Iraq-e Ajami, whereas Transoxiana was first ruled by Sultan Ahmed Mirza from 1469 until 1494 and later divided into Samarqand, Bukhara and Hissar. Most of the northern part of the Timurid Empire was supplanted in 1488 by the Uzbeks, who set up their khanate under Muhammad Shaybani, a Genghisid prince. Soon afterwards, the Kazakh and the Sibir (Siberia) khanates were established, seceding from the Golden Horde. At the same time, Sultan Husayn Bayqara (a great-great grandson of Timur; 1438-1506) ruled (1469-1506) in Herat, continuing the Timurid tradition in terms of patronage of arts and sciences. He thus became a source of admiration for his nephew Babur, who was later the founder of the Mughal Empire of South Asia; but Babur was none else than the grandson of Abu Sa’id Mirza and therefore great-great-great-grandson of Timur.

Last, the southern parts of the Timurid Empire were most;y incorporated into the nomadic Akkoyunlu Empire that also controlled Eastern Anatolia and Mesopotamia; however, internal strives decomposed that empire too around the end of the 15th c. It was then that the mystical Safavid Order, instead of supporting or infiltrating a state, decided to launch its own empire: the Safavid Empire. They already had their own army ready however: the formidable and renowned Qizilbash. About:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timurid_dynasty

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timurid_family_tree

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Mirza

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abu_Sa%27id_Mirza

https://iranicaonline.org/articles/eraq-e-ajami

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abu%27l-Khayr_Khan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Qarabagh

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uzun_Hasan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sultan_Ahmed_Mirza

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Shaybani

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shaybanids

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uzbek_Khanate

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kazakh_Khanate

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sultan_Husayn_Bayqara

—————————————–

List of the already pre-published chapters of the book

Lines separate chapters that belong to different parts of the book.

CHAPTER XII: Parthian Turan: an Anti-Persian dynasty

https://www.academia.edu/52541355/Parthian_Turan_an_Anti_Persian_dynasty

———————————

CHAPTER XIV: Arsacid & Sassanid Iran, and the wars against the Mithraic – Christian Roman Empire

CHAPTER XV: Sassanid Iran – Turan, Kartir, Roman Empire, Christianity, Mani and Manichaeism

CHAPTER XVI: Iran – Turan, Manichaeism & Islam during the Migration Period and the Early Caliphates

—————————————

CHAPTER XXI: The fabrication of the fake divide ‘Sunni Islam vs. Shia Islam’

https://www.academia.edu/55139916/The_Fabrication_of_the_Fake_Divide_Sunni_Islam_vs_Shia_Islam_

——————————————

CHAPTER XXII: The fake Persianization of the Abbasid Caliphate

https://www.academia.edu/61193026/The_Fake_Persianization_of_the_Abbasid_Caliphate

——————————————–

CHAPTER XXIII: From Ferdowsi to the Seljuk Turks, Nizam al Mulk, Nizami Ganjavi, Jalal ad-Din Rumi and Haji Bektash

————————————————

CHAPTER XXIV: From Genghis Khan, Nasir al-Din al Tusi and Hulagu to Timur

CHAPTER XXV: Timur (Tamerlane) as a Turanian Muslim descendant of the Great Hero Manuchehr, his exploits and triumphs, and the slow rise of the Turanian Safavid Order

———————————————————————–

Download the chapter (text only) in PDF:

Download the chapter (with pictures and legends) in PDF: