Pre-publication of chapter XIX of my forthcoming book “Turkey is Iran and Iran is Turkey – 2500 Years of indivisible Turanian – Iranian Civilization distorted and estranged by Anglo-French Orientalists”; chapters XXVII to XXXII form Part Eleven (How and why the Ottomans, the Safavids and the Mughals failed) of the book, which is made of 12 parts and 33 chapters. Chapters XXVII and XXVIII have already been pre-published.

Until now, 21 chapters have been uploaded as partly pre-publication of the present book; this chapter is therefore the 22nd (out of 33) to be uploaded. At the end of the text, the entire Table of Contents is made available. Pre-published chapters are marked in blue color, and the present chapter is highlighted in gray color.

In addition, a list of all the already pre-published chapters (with the related links) is made available at the very end, after the Table of Contents.

The book is written for the general readership with the intention to briefly highlight numerous distortions made by the racist, colonial academics of Western Europe and North America only with the help of absurd conceptualization and preposterous contextualization.

References made to entries of the Wikipedia offer average readers a starting point for their research; they do not signify acceptance and approval of their contents.

———————–

Certainly, the Safavid Empire was not the first Islamic state established by a mystical order; but earlier states launched by mystical orders were either set up in small and remote territories as form of local resistance against the Islamic Caliphate like the Babakiyah (Khurramites) or organized as a secret subversive movement coordinated from mysterious, faraway, unreachable and impregnable headquarters, like those of the Hashashin Isma’ilis (known as Assassins in Western literature). In this regard, at the level of governance, the main difference between the Safavids and the Isma’ilis was the fact that the latter did not try or even plan to proclaim an empire, whereas the former, even before solemnly announcing their empire, felt that they had the task to entirely reshape the Islamic world.

Selim I

Ismail I Safavi

Babur

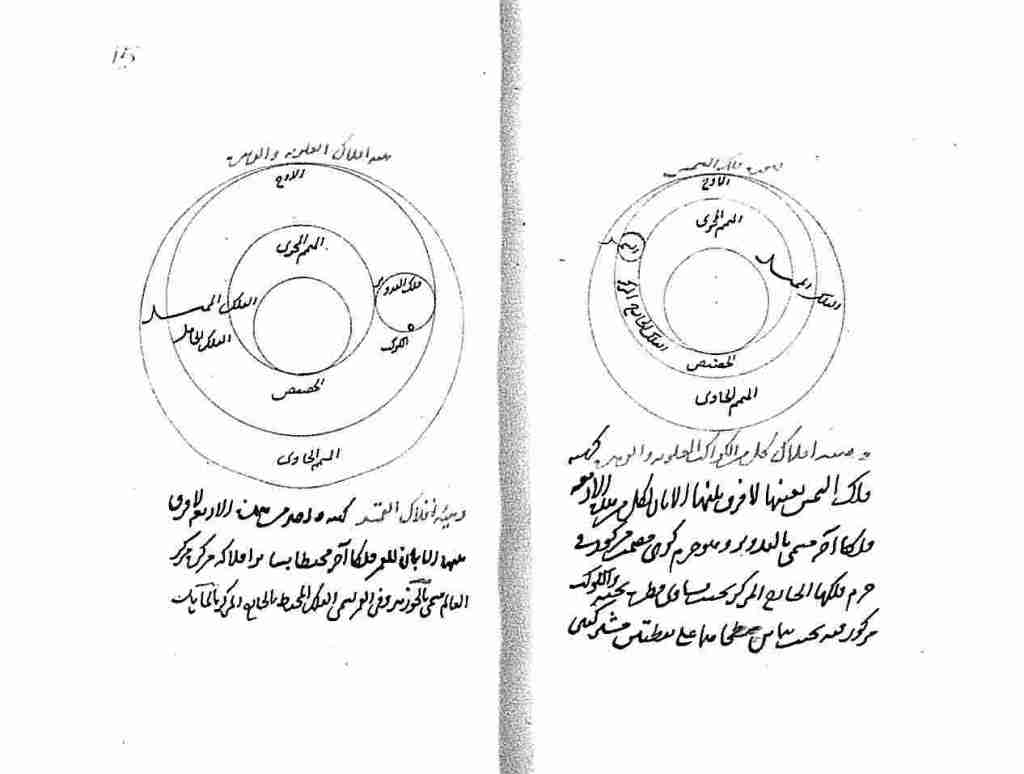

The Safavid Order had the apocalyptic, eschatological and messianic feeling that their task would be the only way to save the Islamic world; they felt that they had the divinely bestowed obligation to institute a secular empire across the Islamic world, which would be based on spiritual values, moral virtues, cultural traditions, and epic revival. The name of the empire was no lees imperial than the following expression: “the Realm of the Outspread Universe of Iran” (ملک وسیعالفضای ایران /Molk-e vasi-ye fezaye Eran); one understands automatically the importance of Ferdowsi’s epic narrative and the cosmological dimension that Safavid spirituality gave to the state that the venerable members of the Order launched. The term ‘Iran’ does not denote either the territory of a nation/ethnic group or the land controlled by a state; all these divisive, nonsensical, modern notions were nonexistent at the time. In the very beginning of the Safavid times, the term ‘Iran’ was not even used.

Prof. Ali Anooshahr, speaking at the symposium “The Idea of Iran: The Safavid Era” (https://www.soas.ac.uk/lmei-cis/events/idea-of-iran/27oct2018-the-idea-of-iran-the-safavid-era.html; Center for Iranian Studies, SOAS; 27 October 2018) about the topic “Historiographical perceptions of the transmission from Timurid to Safavid Iran”, explained how historians of the early 16th c. dealt with the transition from the Timurid to the Safavid period. His speech is available here (from 8:10 until 46:19): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gkvUfU2ruKM

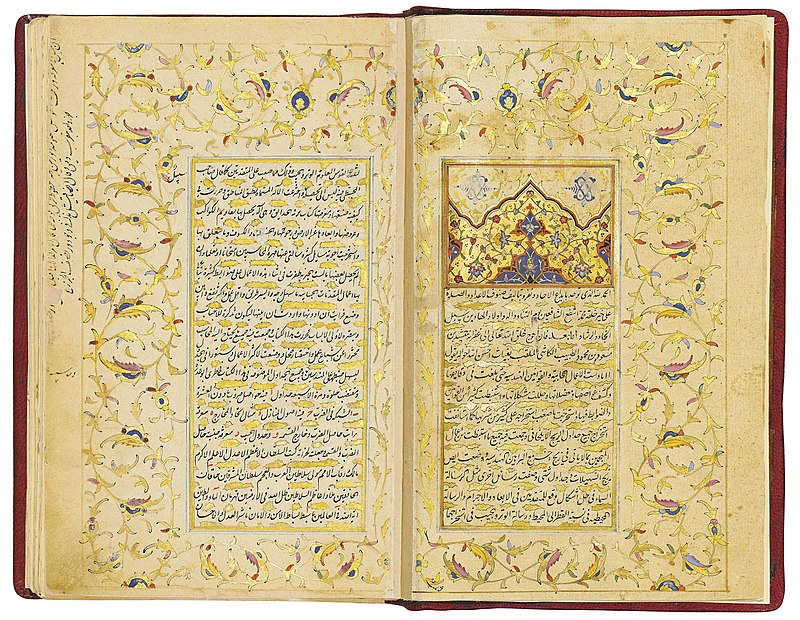

The most important historians of the early Safavid times were Ghiyath ad-Din Muhammad Khwandamir (Habib al-Siyar; Khulasatu-l Akhbar; Dasturu-l Wuzra), Abdallah Hatefi (Khamsa), Amini Haravi (Futuhat-e shahi), Fazli Khuzani Esfahani (Afzal al-tawarih), and Fazl-Allah Khonji Esfahani (Tarih-e alamara-ye amini).

It is interesting to herewith include selected excerpts from Prof. Anooshahr’s well-founded speech, notably (11:30 onwards/no editing involved):

“There was no idea of something called Iran in this transition period”.

“The word ‘Iran’ only shows in Amini’s book twice; once is paired with Turan; and then immediately afterward, when the Rumi (: Roman) envoy shows up on behalf of the Ottoman Emperors”.

“As far as the people of the time were concerned, the actual participants in these events, they had no idea of Iran, and this was not because they were alien or unpatriotic, in fact they were non-patriotic, because there is no patriotism; this was because they had a radically different idea of territory than we do today. So, in our modern conception, people are defined as a nation, they own the land that they live on, and this land has a particular characteristic that is shared between it and all the people”.

“When Amini writes about territory, he sublimates it by using the Quran and comparing it to heaven; he does not connect it to any kind of territorial identity at all”.

“The establishment of Twelver Shi’ism, based on this text, does not seem to be that important. And then the establishment of a kind of Ancient Persian Empire is actually not on their agenda”.

As a matter of fact, Safavid Iran was the entire universe for the members of the Safavid Order, and as such it had no ethnic/national dimension or character and no religious identity. Spirituality was all that mattered. Even more importantly, it was not proclaimed only to encompass the territories that the Safavid emperors finally controlled, as Western Iranologists perniciously suggest, perversely viewing the Safavid empire’s territory as simply a larger ‘version’ of the modern pseudo-state of Iran. For the members of the Safavid Order, “Molk-e vasi-ye fezaye Eran” had the divinely entrusted task to contain the entire circumference of the Islamic world.

Four major monarchs between Rome and China

Between Rome and China, four persons, who played a determinant role in the final formation of major empires and in the final delineation of their borders, were born between 1450 and 1487. In chronological order they are as per below:

i. Muhammad Shaybani (Muhammad Shaybani Khan or Abul-Fath Shaybani Khan; 1451-1510), grandson of Abu’l-Khayr Khan, and Genghisid founder of the Khanate of Bukhara (1500), one of the empires that were formed after the split of the Golden Horde and demise of the precarious Uzbek Khanate; he evidently did not make any distinction between a) Turanians and Iranians (which shows the extent of the completed ethnic Turanization of Iran) and b) those who are fallaciously called today ‘Shia’ and ‘Sunni’ by colonial Orientalists, diplomats or statesmen and Islamic terrorists and extremists alike.

Muhammad Shaybani; 16th c. portrait painted by the famous Iranian artist Kemaleddin Behzad

The fight between Shah Ismail I and Muhammad Shaybani (1510); from the manuscript Tarikh-i alam-aray-i Shah Ismail (the world adorning History of Shah Ismail)

Bukhara; Chor-Bakr burial place constructed under Muhammad Shaybani (1505-1510)

The state of Muhammad Shaybani

ii. Selim I (سليم اول / Yavuz Sultan Selim; 1470-1520), grandson of Mehmed II and son of Bayezid II; he ruled the Eastern Roman Empire only for eight years (1512-1520), but he was by far the most important sultan of the 600-year long dynasty for having expanded the Ottoman territories more than any other. Then, there was no ‘Ottoman Empire’; not one man used that term at the time. The term ‘State of the Ottoman family’ (دولت عليه عثمانیه / Devlet-i ‘Alīye-i Osmaniyeh) was introduced centuries later. Selim I was the Padishah (پادشاه), i.e. the ‘Great King’, thus bearing an Iranian title that goes back to the early Achaemenids who antedated him by two millennia. Selim I was also (βασιλεύς Ρωμαίων / Imperator Romanorum / قیصر روم / Qaysar-i Rum, lit. “Caesar of the Romans”) like his father and grandfather after 1453, because Mehmed II claimed the title after conquering Constantinople, George of Trebizond endorsed the claim, considering Mehmed II as emperor of the world, and Gennadius Scholarius, Patriarch of the Eastern Orthodox Church, fully recognized the title.

The state of Selim I was also viewed by others as the Roman Empire (in the sense of the Eastern Roman Empire, because the Western Roman Empire ceased to exist in 476 CE). From the aforementioned speech of Prof. Ali Anooshahr, I quote another excerpt here (exactly after 12:07 in the above mentioned video and link):

“I am referring to what we call ‘the Ottoman Empire’; but if the topic today is to look at how people perceived their own territoriality, then we shouldn’t call it ‘the Ottoman Empire’, because they didn’t call it that way; they called it ‘the Roman Empire’ (ruled by the Ottoman family)”.

Selim I was not styled “Commander of the Faithful” (أَمِير ٱلْمُؤْمِنِين / ‘Amir al-Mu’minin) for most of his reign, and when he could claim the title, the majority of his subjects rejected it for him. The same concerns the later and minor title “Servant of The Two Holy Cities” (خَادِمُ الْحَرَمَيْن / Hadimü’l-Haremeyn), which is somewhat a historical novelty introduced only as late as the 12th – 13th c. Last, it is only after 1517 that Selim I was accepted as ‘Caliph’ throughout his realm and dependencies.

Selim I (Yavuz Sultan Selim); portrait painted by the Ottoman artist Nakkaş Osman (16th c.)

The territorial expansion of the Ottoman Sultanate (focus on Anatolia and the Balkans)

Portrait (end of 18th-beginning of 19th c.) painted by the Christian Orthodox Eastern Roman artist Konstantin Kapıdağlı (Κωνσταντῖνος Κυζικηνός; Konstantinos Kyzikinos)

Ottoman Empire around 1520

Miniature from the 16th c. manuscript Hüner-nāme; I, Library of the Topkapi Palace Museum

The Ottoman Empire in 1875

Sultan Selim I and the Grand Vizier Piri Mehmed Paşa

Selim I portrait painted by Aşık Çelebi

Painting showing Selim I during the Egypt campaign, Army Museum, Istanbul

Portrait of Selim I painted by Paolo Veronese (Paolo Caliari); Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen – Staatsgalerie in der Residenz Würzburg

From the personal belongings of Shah Ismail that were captured by Selim during and after the Battle of Chaldiran. Topkapi Museum, Istanbul

iii. Babur (ظَهير اَلَدّين مُحَمَّد – Zahīr ud-Dīn Muhammad; 1483-1530) was the eldest son of Umar Sheikh Mirza, the Timurid governor of Ferghana who was the son of Abu Sa’id Mirza; consequently, Babur was the great grandson of Abu Sa’id Mirza’s father, Sultan Muhammad Mirza, governor of Samarqand for some time, whom due to an unknown reason Babur did not even mention in historical boon Babur-nameh. This implies that Babur was the great-great grandson of the father of Sultan Muhammad Mirza, Miran Shah, who was the third of Timur’s four sons. So, Babur was the great-great-great-grandson of Timur.

If he is basically known through his nickname (‘tiger’), this happens because he truly deserved it. Babur became the ruler of Ferghana at the age of 11 (in 1494), and he was an outstanding and exceptional adolescent in every sense. In his rather brief but most eventful life that had unprecedented ups and downs, Babur had to incessantly fight hard for long and in a most adventurous and often thunderous manner, undertaking campaigns, laying sieges, and winning battles, but also losing his capitals. He was defeated by Muhammad Shaybani, and he spent years in humiliation and poverty without a real shelter.

However, he managed to capture Kabul (1504) and to control parts of today’s Afghanistan; he then benefited from Ismail I’s victory over Muhammad Shaybani (1510), recaptured Samarqand, and prepared his army for the major campaign and the greatest success of his life, namely the invasion of the Indus River and the Ganges River valleys, the demolition of the Delhi Sultanate, and the foundation (1524-1526) of the Mughal Empire (1526-1858). So, triumph came at last to this intellectual soldier and philosopher-conqueror. By all means, Babur would have made -in a terrible historical irony- the perfect son to Timur himself!

iv. Ismail I Safavi (1487-1524) was none other than the son of Shaykh Haydar, the Grandmaster of the Safavid Order and the founder of the Qizilbash military order. It is noteworthy that his maternal grandmother was none other than Despina Hatun, i.e. Theodora Megale Komnene, of John IV of Trebizond, who became Muslim to get married (1458) with Uzun Hassan, the Aq Qoyunlu sultan, whose daughter Martha (mainly known as Alamshah Halime Begum) -in very young age- got married (1471) with Shaykh Haydar.

However, tribally and imperially, Ismail I’s lineage was not as important as the ancestry of Muhammad Shaybani, Selim I, and Babur, but his spiritual-mystical backing was incommensurately stronger; people of different origin, occupation and location could instantly rush to his support and give their lives personally for him. And his great military advantage was his unpredictability, which was due exactly to his spiritual-mystical backing. His opponents would never know from where his fighters would surface to protect him and defend his cause.

Contrarily to Muhammad Shaybani who had the youth of a regular soldier, and to Selim I who spent years in palatial intrigues as he was his father’s third son, Ismail I was an exceptional youngster like Babur; but his father’s spiritual potency made an enormous difference. This is difficult to assess properly today, but in the circle of the Anatolian-Caucasus-Iranian-Central Asiatic members of the Safavid Order and the Qizilbash fighters, Shaykh Haydar was believed to be God Incarnate (elah) – in the spiritual (not theological) connotation of the word. This meant nothing less than an absolute faith as per which the infant Ismail, long before establishing the Empire of the Safavid Order, was believed to be ‘ebn Allah’ (Son of God).

Western colonial historians and Orientalist forgers, in their incessant effort to distort the historical reality of the Safavid times, select deliberately anti-Safavid authors of those days, like Fazl-Allah Khonji Esfahani, take their premeditated narratives at face value, attach to them several fake, pseudo-Islamic theological concepts, such as the ‘ghulat’, and portray the Safavids as ‘Shia extremists’ or ‘antinomians’ (another fake term), which is absolutely absurd. As said in the previous chapter, there cannot be religious evaluation of spiritual matters; this means that every attempt of theological interpretation of a spiritual term or expression is a failure already before it is stated. In fact, there are no ‘ghulat’ at all.

This term is a neologism, which is attributed by modern scholars to various mystics and spiritual masters (of different Islamic periods), who were misunderstood in their times by their theological critics. The perverse colonial interest in promoting the ‘ghulat’ bogus-literature and in using the fake term for people, who were not called ‘ghulat’ in their times, is due first, to the Western academics’ distortive effort to generate the nonexistent ‘Sunni vs. Shia’ divide, and second, to the Western intellectuals’ vicious attempt to portray several Muslim mystics and spiritual grandmasters as ‘heretics’, whereas the difference between Islam and Christianity hinges exactly on this point, namely that there cannot be ‘heresy’ within Islam.

Ismail I was undoubtedly an extraordinary youngster who lived in strict mystical seclusion for five years (from 7 to 12), before appearing as almost the Islamic Messiah (Mahdi). It is necessary to straightforwardly clarify at this point that this term has a totally different meaning in spirituality and in religion (or theology). Meanwhile, the bright and exceptional apprentice was communicating with several members of the Safavid Order and the Qizilbash army though a sophisticated network of agents that was too difficult for others to identify, let alone put under control.

For Ismail I Safavi’s early stage of life (during those five years), there were certainly several parallels between his concealed existence and that of Muhammad ibn al-Askari, the Twelfth Imam (who was born in 869 and finally disappeared in his Major Occultation in 941). However, only theological misinterpretation of spiritual activities and narratives could lead to the wrong assumption about an eventual identification of Ismail I with Muhammad ibn al-Askari. Not one member of the Safavid Order was confused in this regard.

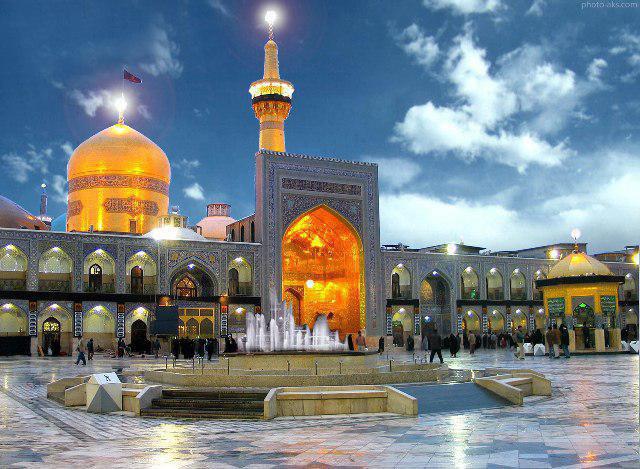

After having lived his childhood in the forests of Gilan, he appeared to his brethren and followers at 12 (in 1499), he achieved an unexpected, great victory over the Shirvanshah ruler Farrukh Yassar two years later (1501), and he was crowned king at 14. Thus, he was catapulted to power in the most exulting terms, whereas his merry, exuberant and legendary entry to Tabriz was followed by endless feasts, imperial banquets, endless consumption of wine, and fabulous erotic delights.

He who says that wine (or alcoholic drinks in general) is prohibited in Islam is either a conniving Westerner (diplomat, statesman, agent or academic) strongly motivated by his vicious hatred of the true, historical Islam or an idiotic puppet of the Western powers, i.e. an ignorant and idiotic, fanatic and extremist, Islamist sheikh, who – as per the Satanic orders of his Western masters – believes that “Islam is the Quran and the Hadith”. Quite contrarily to this fallacy, the extensively misinterpreted and calamitously misunderstood sacred texts of Islam do not represent even 0.001% of the existing voluminous literature (in classical Islamic languages, namely Arabic, Farsi, various Turkic languages, and Urdu), which has to be first studied, then correctly perceived and plainly comprehended before one attempts to read the Quran and the Hadith. No holy text exists without exact conceptualization and comprehensive contextualization.

The sacred texts of Islam (similarly with those of every other religion) cannot be accurately and succinctly understood per se except in the light of literary, spiritual, historical, theoretical and scientific texts of the Golden Era of Islam. The same occurs in Christianity; without the Patristic Literature (Patristics or Patrology, i.e. the texts written by the Fathers of the Christian Church) no one can possibly understand correctly the New Testament, the Old Testament, and the true, historical Christianity. The fallacy, as per which anyone today can understand the Gospels and the other sacred texts of Christianity without the Patristic Literature, is a deviate, Protestant – Evangelical distortion.

The aforementioned four Muslim emperors were all authors, poets and highly educated and cultured monarchs. Muhammad Shaybani composed his Bahr ul Huda, a theological, moral treatise, being widely known as a consummate polymath and an erudite scholar who highly valued books, manuscripts, epics and arts. Selim I wrote poetry in Farsi and Turkish under the penname Mahlas Selimi. Babur excelled in prose; he elaborated his own biography in Chagatai Turkic; the legendary Babur nameh (Book of Babur) is a major historical source for the History of Asia during the 15th and 16th c.

Ismail I Safavi composed spiritual poetry in Turkish and Farsi under the penname Khatai, i.e. ‘the one who makes mistakes’; in and by itself, this fact constitutes the complete confirmation of the aforementioned statement, namely that there cannot be religious evaluation of spiritual matters. Confessing one’s own mistakes -by selecting a name that makes this reality so explicitly known- is full indication of humanity; a perfect human accepts that he/she makes mistakes. By using this penname, Ismail I fully demonstrated that the term ‘ebn Allah’ (Son of God) attributed to him was not meant in a rationalistic theological way but in terms of spiritual symbolism, which is absolutely unfathomable to juristic, rationalistic and materialistic theologians.

In the existing manuscripts (preserved in Tashkent and Paris) of Ismail I Safavi’s poetry, there are ca. 260 qasidas and ghazals, quatrains, morabbas, mosaddas, and three mathnawis (different types of Islamic poetry); two of his mathnawis are quite lengthy, namely the Dah nameh and the Nasihat nameh. Bektashis in Anatolia and the Balkans, as well as the Shabaks in Mesopotamia, extensively recite Ismail I Safavi’s poetry in their spiritual sessions down to our days.

The interaction of those four great emperors was not trouble-free, peaceful and bloodless; at times, it even took a dimension of extreme monstrosity. During the period 1497-1504, Babur and Muhammad Shaybani were repeatedly engaged in battles against one another, particularly for the control of Samarqand. Muhammad Shaybani proved to be Babur’s real nemesis, but both of them captured, lost and recaptured Samarqand several times. As Babur had a small basis of support in Central Asia, he undertook a most adventurous campaign in 1504, and with few men he captured Kabul, making of the area his new base. He made an alliance with a distant relative, namely the ruler of Herat Sultan Husayn Mirza Bayqarah; but Muhammad Shaybani chased him from there too.

As Muhammad Shaybani was an ally of the Ottoman family and of Bayezid II, the father of Selim I, he concentrated his efforts in the East and Southeast, against the Hazara Turanian nomads in Khorasan (currently located in central Afghanistan) and the Kazakhs. In fact, his campaign against the Hazaras was a disaster, because first his cavalry had many casualties and second the war against the Hazaras produced a major reaction among the Qizilbash, because many members of the military order were of Hazara origin. Then, Ismail I Safavi, who had spent many years, invading and dismantling the Akkoyunlu state and its last remaining forces in Iran, Caucasus, Eastern Anatolia, and Mesopotamia, turned against Muhammad Shaybani. Then, in the Battle of Merv, the Qizilbash army, after devising a trick (i.e. a feigned retreat), ambushed and slaughtered an almost double Uzbek force.

The excesses after the Qizilbash victory were exorbitant; Muhammad Shaybani’s corpse was cut to pieces and parts were sent to be in public display in many cities; his skull ended up as a gold-plated cup for Ismail I. The cup was later sent to Babur himself, and the same occurred to one of Muhammad Shaybani’s wives, namely Khanzada Begum, who was Babur’s elder sister. These gestures started an era of cooperation between Ismail I, who had just risen to prominence, and Babur whose army and the Qizilbash fought side by side against the Uzbeks at the Battle of Ghazdewan (1512); however they were defeated there, and this event marked the end of Babur’s dream of recovering his father’s kingdom at Ferghana. For some time, Babur accepted Ismail I as his own emperor, while he was struggling to impose his rule in the mountains between Central Asia and the Indus River valley.

Opposing Ottoman allies at the Battle of Ghazdewan, Babur (today portrayed as a ‘Sunni’ by colonial Orientalists) became an ally of Ismail I Safavi (currently labeled as a ‘Shia’ by European and American historical forgers) and therefore an enemy of Selim I (nowadays described as a ‘Sunni’ by Western academics). The reality is totally different: Ismail I was a spiritual mystic, who became the ruler of a secular empire controlled by the army (Qizilbash) of his mystical order (Safavid), whereas Selim I was a palatial intrigue man controlled by evil theological circles and people who caused divisions, civil wars, internal strives and terrible bloodshed in the Eastern Roman Empire (of the Ottoman family). Then, in striking opposition with both, Babur was an intrepid, intelligent and opportunist, yet formidable, soldier entirely motivated by the dream to create an empire greater than his father’s and Timur’s.

The spread of Qizilbash force, movement, worldview, mentality, and lifestyle among Anatolian pastoralists was overwhelming in the 1500s. It triggered its own dynamics, which was not controlled anymore by the Safavid Order and the newly established Safavid Empire. The mystical order of Şahkulu was the perfect continuation of many long centuries of Anatolian Islamic spirituality and mysticism; it was energized by the introduction of the Qizilbash concept (an army for a mystical order that would establish a secular universal empire).

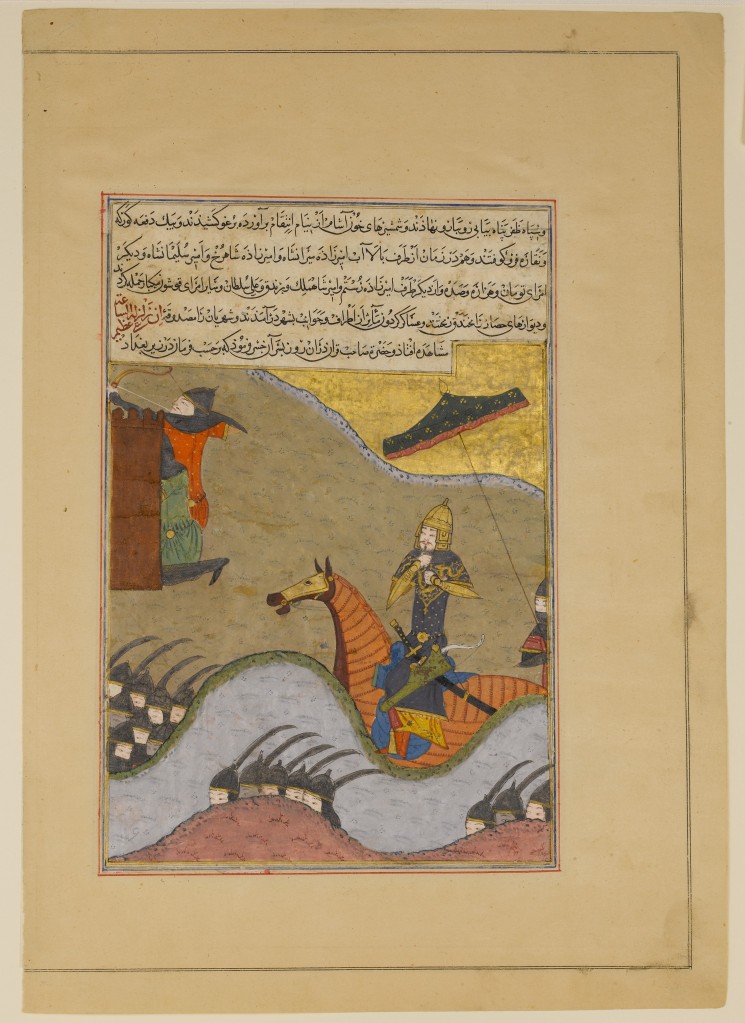

Ismail I Safavi in an incident from his campaign against Shirvan; he is charging down a mountain in pursuit of the King of Shirvan; miniature from the manuscript Shahnama-i-Ismail (Tabriz style), ca. 1540 (MS Add. 7784, f.46v. British Museum, London); his distinctive turban has twelve folds representing the twelve Imams of whom Ali ibn Abi Taleb was the first.

The Aq Qoyunlu tribal khanate (1378-1503) around 1475, i.e. 25-30 years before it was defeated and incorporated with the Safavid Empire

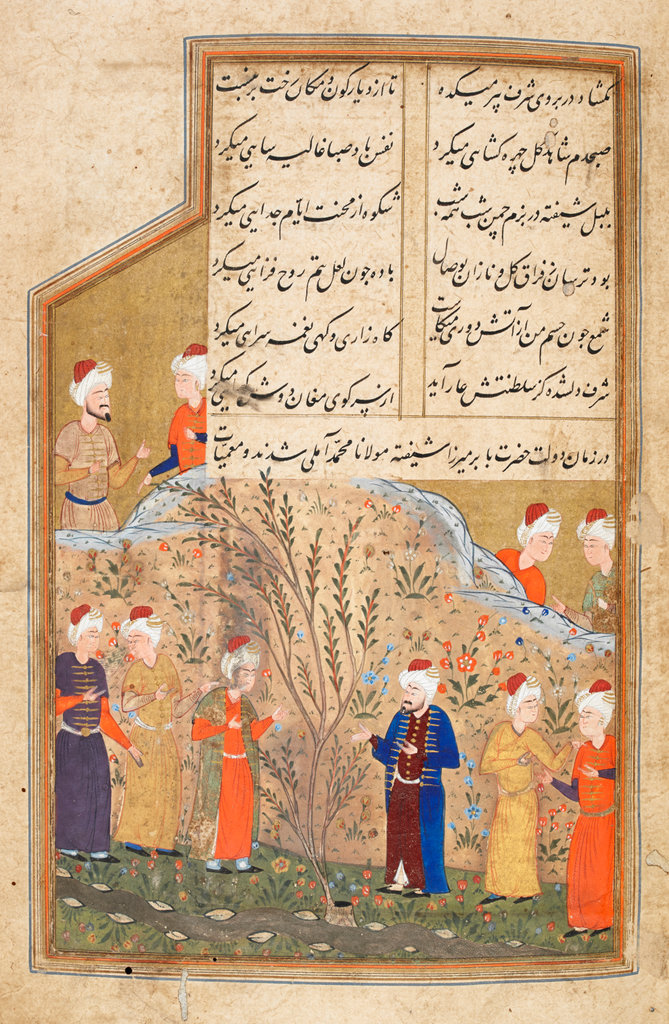

Miniature from a 17th c. manuscript with mystical representation of Sheikh Safi ad-din Ardabili (1252-1334) blessing the young Shah Ismail I; gouache heightened with gold on paper. The historic mystic is depicted at the top of a minbar in the mosque holding a Qur’an and blessing Shah Isma’il (identified in small brown script) who stands on a lower step of the same minbar, surrounded by courtiers and elders.

Ismail I Safavi offers an audience to the Qizilbash, after they have defeated his opponent Shirvanshah Farrukh in 1500; miniature from Bijan’s Tarikh-i Jahangusha-yi Khaqan Sahibqiran (A History of Shah Ismail I), which was written in Isfahan in the late 1680s. The painting was created by Muin Musawwir, a famous artist who also illustrated six editions of the Shahnameh.

Ismail I Safavi and his soldiers cross Kura River in the Caucasus region

Ismail I Safavi defeats Sultan Murad, the last ruler of the Aq Qoyunlu, near Hamadan in 1503.

Miniature from a manuscript of Bijan’s Tarikh-i Jahangusha-yi Khaqan Sahibqiran (A History of Shah Ismail I), which was written in Isfahan in the late 1680s. It was painted by or in the style of Mu’in Musavvir; gouache heightened with gold on paper. Ismail and his courtiers are depicted on horseback while hunting.

The fight of Ismail I Safavi against the Dulkadiroğulları in Southeastern Anatolia

Ismail I Safavi watches his soldiers defeat the Musha’sha (المشعشعية) messianic leader Sultan Fayyad in Khuzestan; from the miniature of a manuscript of the late 1680s.

Representation of the Battle of Merv between Shah Ismail and Shaybani Khan; fresco in the Chehel Sotun Palace in Isfahan

Ismail I Safavi’s envoy Ganbar Agha appears before the last Aq Qoyunlu ruler Sultan Murad; miniature from a manuscript of the 1670s

Representation of the Battle of Chaldiran (1514); fresco in the Chehel Sotun Palace in Isfahan

The helmet of Ismail I Safavi

The Şahkulu Spiritual Movement

However, the Anatolian mystical order was not stricto sensu created by the Safavid Qizilbash. Many Western Orientalists totally misinterpret the role, the scope, the targets and the motivations of the founder and grandmaster of the eponymous order; Şahkulu (also known as Shah Qoli Baba or Shah Kulu or Shah Quli or Karabıyıkoğlu, i.e. the son of the man with black moustache) was certainly not a Safavid puppet who attempted to subvert or infiltrate the Ottoman state; this misinterpretation is absurd. Şahkulu was an Anatolian original.

In this regard, colonial academics totally distort everything, even the real meaning of Şahkulu’s name! It is true that in Turkish, this word means ‘the servant of the Shah’; however, this is not meant in a theological and rationalist manner, but with a purely spiritual connotation. Şahkulu was indeed the ‘servant’ of the ‘Shah’, but according to the terminology of an Islamic mystical order, ‘Shah’ is God. In fact, even worse lies and incredible distortions are published by Western colonial historians as regards the bloodshed, the persecution and the oppression of the Anatolian Qizilbash by the usurper of the Ottoman throne Selim I. The reason for these lies is evident: on the misrepresentation of the historical events that took place in Anatolia during the dramatic period 1510-1512 hinge both, the entire falsification of the Ottoman History and the fallacious theory that “the Ottomans were Sunni and the Safavid Iranians were Shia”. In addition, Western historians tried systematically to obscure the fact that the Ottoman ruling class followed Maturidi theology, whereas the uncontrolled but intentionally tolerated majority of the madrasas and the imams were impacted by Ash’ari concepts.

As a matter of fact, the so-called Şahkulu İsyanı (rebellion), which was not an uprising but a messianic fervor, and the subsequent events, namely the battle of Chaldiran (1514) between Selim I and Ismail I, bear witness to the gradual rise of a pseudo-Islamic theological school at Istanbul (under the Hanafi madhhab coverage). Those indoctrinated and ignorant sheikhs progressively destroyed the Ottoman Empire with their absurd inhumanity and obdurate idiocy, which invariably took the form of nonsensical argumentation, strict anachronism, theological rigidity, verbal rationalism, worldly materialism, and nonsensical involvement in the governance of the expanding empire. Their worst and most catastrophic trait however was their explicit revilement and utmost hatred of Islamic spirituality (Batin/ باطن; Batiniyya/ باطنية; these terms literally means ‘inner’ and ‘esotericism’, but they have nothing to do with Western esotericism/mysticism).

These Istanbulite theological circles were not powerful at the time, but gradually, during the 16th c., they managed to prevail within the Ottoman court; their achievement was the destruction of Taqi ad-Din Muhammad ibn Ma’ruf’s Islamic Observatory of Istanbul in 1580 – an event that marks the irrevocable death of the Islamic Civilization. In 1510-1512, the same theological circles plunged Anatolia in terrible bloodshed; this was due to their determination to oppose the prevalence of Şahkulu Qizilbash spirituality. That’s why these pseudo-Muslim theological circles always represented the ‘enfant gâté’ of Western academics: they constituted indeed the perfect guarantee for the destruction and the disappearance of Islam, because they could be (and they were) easily induced by Western colonial agents to trigger interminable divisions and fratricidal wars among the Muslims.

Selim I was not predestined to become a sultan, as he was the fourth among the eight sons of Bayezid II. Şehzade Abdullah was the first among Bayezid II’s eight sons, but he died young in 1483; Şehzade Şehinşah was the Ottoman sultan’s fifth son and he was very well educated and militarily strong, but he never gained the support of the Ottoman bureaucracy, administration and theological nomenklatura. Although governor of big cities and loved by the people of Karaman, he died in 1511 for unknown reasons, possibly poisoned by some vicious Ottoman theologians. Born in 1465, Ahmet (known as Şehzade Ahmet; 1465-1513) was the second son of Bayezid II; born in 1467, Korkut (known as Şehzade Korkut; 1467-1513) was the third son of Bayezid II. Şehzade Mahmud (1475-1507), the younger brother of Şehzade Ahmet, died in 1507 for undefined reasons. Seventh son of Bayezid II was Şehzade Alemşah (1477-1502) who also died in 1502 or 1503 for unspecified reasons.

Compared to Şehzade Ahmet and to Şehzade Korkut, Selim I (born in 1470) was a far cry and an unimportant prince, even more so since Bayezid II’s favorite candidate to his succession was Ahmet. However, the Ottoman court had always been a matter of Istanbulite palatial intrigues, intra-family fights, and endless fratricides, pretty much like those occurred during the Eastern Roman times in God-damned Constantinople. Bayezid II (1447-1512; his reign started in 1481) had to fight to secure his succession, because Cem Sultan (1459-1495), his younger brother, laid claim to the throne. Selim I was an insubordinate, rebellious, idiotic and absolutely unworthy son, who was manipulated by the evil Istanbulite theologians as to how to plot, cheat and connive against his own father. This is what the pseudo-Islamic madhhab (jurisprudential schools) and theological schools were reduced to at those days – and ever since down to our days.

Selim I rebelled against his father not for any other reason, but because the vicious theological circles of Istanbul, which are nowadays mistakenly called ‘Sunni’, wanted to use him against the spread and the rise of the Şahkulu Anatolian spirituality. The succession to the throne of Bayezid II was only the pretext. In fact, Ahmet (Şehzade Ahmet) did not only have the right of primogeniture, but also his father’s consent and favor; that’s why the disloyal son and puppet of Istanbul’s evil theologians Selim I had to ceaselessly plot against his father.

In addition, there was a confusing and disastrous tradition in the Ottoman family, as per which among the dying sultan’s sons, whoever reached the dead monarch’s bed first would (or could eventually) become his father’s successor. A clear sign of the chaotic situation that prevailed in the Istanbulite palace of the disorderly, lawless and faithless family was the disastrous fact that, in order to make sure that the eventually insubordinate crown princes and the other princes would not fuel a rebellion against the sultan, the Ottoman rulers used to send their sons to faraway provinces in order to serve there as local governors – which in turn reduced their chances to successfully plot. This meant that distance mattered greatly at those days!

Ahmet was the governor of Amasya in Northern Cappadocia (675 km from Istanbul), Korkut was the governor of Antalya (then called Teke, in Pamphylia) in the southern coast (640 km from the capital), and Selim was the governor of Trabzon (1060 km from his father’s palace). In that ridiculous situation, everyone was preparing for the forthcoming confrontation; it was therefore normal that Ahmet rejected his father’s appointment of Suleyman (son of Selim I, who became later known as Suleyman the Magnificent) as governor of Bolu, because of the small distance that separated the tiny and insignificant city from the Ottoman capital (only 260 km). Suleyman was then sent to the Ottoman Crimea (Kefe or Kaffa or Caffa; today’s Feodosia).

Incessantly plotting, Selim asked his father to appoint him as governor in a sanjak in Rumeli (: Balkans). Bayezid II rejected this bizarre demand because the Ottoman sanjaks in the European territory of the empire were smaller, more recently acquired, and unfit for princes. This fact shows that Anatolia was always the central and most important part of the Ottoman state, as it was of the Eastern Roman Empire in earlier periods.

Involving foreigners in acts against his father’s decisions and affairs, Selim asked the help of the Tatar Khan of Crimea and he was finally appointed as governor of the pashalik of Belgrade (then named in Turkish as ‘Semendire Sancağı’, i.e. Sanjak of Smederevo), which is located at a distance of 900 km from Istanbul. However, instead of staying at the headquarters of his administrative province, the disloyal, immoral and faithless Selim approached Istanbul, and then Bayezid II had to fight against him and defeat him in August 1511. Selim escaped to his Tatar friends in Crimea, but at the same time, the Şahkulu spiritual movement and the ensuing messianic fervor took disproportionate eschatological dimensions in Anatolia, and the sultan tasked Ahmed to impose order and discipline through the Ottoman Empire’s eastern provinces.

As a matter of fact, there was never a Şahkulu rebellion, contrarily to what most of the historians claim nowadays. There was instead a passionate messianic fervor and the Ottoman attempt to suppress the spiritual movement was met with resistance. This situation cannot be termed as ‘rebellion’, because there was no intention for rebellion among the members and the followers of the Şahkulu mystical order. They did not want to overthrow any authority or to impose themselves as the rulers. As every spiritual movement brings forth liberation and salvation, a large number of people across Anatolia viewed in the Şahkulu movement and in their Qizilbash army the promise and the perspective of a better life free from the Ottoman family’s incompetence and incessant butchery and bloodletting; but this was not tantamount to public disobedience or disorder.

As spirituality enables the faithful to understand the real purpose of this life and of the Hereafter, the Şahkulu members, followers and army knew quite well that the Ottoman princes had absolutely no legitimacy to possess the wealth they garnered and to hold the positions they had. In terms of spirituality, states do not exist or are not needed; these evil social structures have absolutely no value and no authority for any spiritual mystic and any spiritually-awakened person.

Şahkulu Qizilbash army raids on cities, on Ottoman treasures, on imperial caravans, and on regional administration centers started therefore becoming very frequent around 1510. It is essential for both, experienced historians and erudite readership, not to evaluate those developments with today’s average Western mentality and approach; there was nothing illegal in those acts. They were absolutely just, moral and lawful; even more importantly, they were viewed as such by the outright majority of the Anatolian populations. In any case, ‘lawful’ is only the ‘just’ and the ‘moral’, in striking contrast to the modern Western societies and their lawless laws, criminal nature, and evil states that are all doomed to perish.

The historical reality was as simple as that: the Qizilbash soldiers were not thieves; quite contrarily, the Ottoman princes, administrators and theologians were crooks. Şehzade Korkut’s caravan was attacked once, whereas the beylerbey of Anatolia (Anadolu) was defeated, when he tried to engage the Şahkulu forces in battle. Then, Bayezid II realized that his empire was about to crumble in Anatolia; he therefore sent Şehzade Ahmet (1511) and the Grand Vizier Hadım (: eunuch) Ali Pasha in order to protect his, his family’s, and his gang’s lawless interests. I severely criticize the Ottoman sultan because he was ruling his realm as a disgrace; when a ruler is not just, moral and lawful, it is the plain right and duty of every person to take justice in his hands.

The dispatch of Şehzade Ahmet happened at the same time, when Bayezid II was fighting against his lawless, faithless and rebel son Selim; this was a development Şehzade Ahmet had to keep a close eye on. During the battle against the Şahkulu forces (near Kütahya), Şehzade Ahmet tried therefore to close a personal deal and an alliance with Şahkulu Karabıyıkoğlu himself; in other words, he attempted to gain his support, as well as that of his movement and of the Qizilbash army for the succession to the Ottoman throne. This would be an excellent solution for all, namely the local populations, the Anatolian Qizilbash, the messianic mystic, and the heir of the Ottoman throne.

Şehzade Ahmet’s attempt to ascend to power with the support of the Şahkulu movement, if it brought forth great results, would make of the Ottoman Sultanate {then still called ‘(Eastern) Roman Empire’} a perfect copy of the Safavid Empire: a Turanian Empire ruled by a spiritual order. This would trigger exceptionally positive and truly propitious changes across the Islamic world, entirely revivifying Islamic spirituality and terminating the catastrophic theological indoctrination, which finally prevailed and gradually destroyed the Islamic World totally.

Of course, Şehzade Ahmet was not a mystic and he acted only out of his personal interest. Şahkulu Karabıyıkoğlu tried then to gain him to his own cause; however, the affair was very risky, and unfortunately the news leaked. Then, Şehzade Ahmet had to persuade Hadım Ali Pasha that the scope of the negotiations was other, ask him to continue the battle against the Qizilbash army, and run to major Anatolian cities to gain wider regional support for his ascension to the Ottoman throne. The correct place for this was Konya, the leading center of Anatolian spirituality.

The forces of Hadım Ali Pasha pursued the Şahkulu Qizilbash army and after several minor engagements, in the battle of Çubukova (Eastern Cappadocia), both Şahkulu Karabıyıkoğlu and Hadım Ali Pasha were killed (July 1511). However, the Qizilbash force was not dispersed and remained actively powerful. Having prevailed over his rebellious son Selim in August 1511, the embattled Bayezid II had to deal with the chaotic situation of his empire in Anatolia. As Şehzade Ahmet controlled Konya and disobeyed his father’s order to return to his position, Bayezid II believed that the true reason for the spread of the Şahkulu movement was Ismail I; this was a very wrong conclusion, because the Anatolian Qizilbash force was totally independent from the Safavid state. Actually, in the ensuing exchange of royal correspondence, Ismail I totally rejected any involvement in the Şahkulu events in Anatolia; he even went on to explicitly condemn the Anatolian Qizilbash attitude and practices.

Meanwhile, Şehzade Ahmet attempted to advance to Istanbul and dethrone his father, while Selim was in Crimea; however, he failed to advance, as he was blocked by the imperial guard before Bursa. At the same time, Selim gathered a Tatar force and, relying on the Istanbulite theologians’ and bureaucrats’ timely messages and direct support, returned to Istanbul in April 1512 and dethroned his father; no less than a month later (26 May 1512) Bayezid II died dishonored in shameful exile (in Dimetoka, today’s Didymoteicho/Διδυμότειχο on the Turkish-Greek border).

The confrontation between Şehzade Ahmet, who had gathered Qizilbash support in the meantime, and Selim I took place in April 1513 near Bursa, and after an initially indecisive clash, Şehzade Ahmet was defeated and killed. Although Şehzade Korkut had accepted his younger brother’s reign in 1512, Selim I had him killed too, in 1513. An extraordinary purgatory took then place against all the remaining nephews of Selim I, so that the bloody reign of the Ottoman butcher may not be endangered in any way; this would also concern particularly Şehzade Murad, the son of Şehzade Ahmet, who was viewed by the outright majority of the Anatolian population as the rightful heir to the Ottoman throne. However, Şehzade Murad was clever enough to escape to Eastern Anatolia, which was totally out of Ottoman control, communicate with Ismail I, get his support, and coordinate with other Turkmen and Qizilbash forces in order to oppose and eventually overthrow Selim I.

The terrain of the Şahkulu movement

Full of hatred, rancor and hysteria, Selim I carried out an unprecedented ‘white terror campaign’, killing dozens of thousands of civilians under the fake pretext of supporting the Qizilbash army; numbers vary in several historical sources, but an estimate of 50000 people would not be far from truth. This extraordinary bloodshed took place in only one third of today’s Turkey’s territory, namely Western Anatolia. Subsequently, a great number of captives were sent to Rumeli (European provinces of the Ottoman state) and finally settled in Mora Eyalet (ایالت موره; Eyalet-i Mora, today’s Peloponnese in southern Greece).

After the previous description, it becomes clear why, in today’s absurd, disastrous, anti-Turkish and pseudo-Islamic regime of Turkey, one can find journalists who still remember the illustrious Şahkulu movement, having however shaped a disastrously mistaken opinion about it. The so-called ‘political islam’ was indeed fabricated by the French, English and American Orientalists in order to entirely replace the traditional knowledge of the Muslims about the true historical Islam; for this project, an entirely fake History of the Islamic World was scrupulously written, taught and propagated by thousands of Western Orientalist forgers over the last 200 years.

The Islamic forgery of the Western academics did indeed match the ideological forgery that is known as ‘political islam’: they proved to be the two sides of the same coin. The scope of Western Islamology (or ‘Islamic Studies’) was exactly to come up with narratives, which would offer venues to all the Islamists and to the stupid Muslim followers of ‘political islam’ to misperceive the Şahkulu movement (and generally, the entire History of the Islamic World) and to thus shape a totally distorted idea about this topic (and about thousands of other topics). This was done in order to engulf all the Muslims in a totally false perception of the History of the Islamic World, and in an absolutely compact ignorance of their past and heritage.

The fallacious contextualization of the history of the Şahkulu movement had therefore started long before the English secret services selected the ignorant street seller Erdogan for the position to which they raised him, duly fooling the Turkish military, academics, politicians, and businessmen. As he functioned as the prefab puppet of the worst enemies of the Muslims, a false reading of the History of Islam spread throughout Turkey (as it had already been the case in all the other Muslim countries which, contrarily to Turkey, were colonized). As a matter of fact, nowadays all the worthless theologians and disreputable sheikhs of Diyanet (Turkey’s so-called ‘Directorate of Religious Affairs’) are the equivalent of the uneducated, idiotic and evil theologians of the times of Selim I.

A typical example of historical distortion concerning the Şahkulu movement in today’s Turkey is offered by the shameless villain and crook Murat Çolak who published a ridiculous article in the local newspaper of Kahramanmaraş (formerly Germanikeia) ‘Maraş Gündem’ on the 16th July 2018 under the nonsensical title “FETÖ’nun Tarihsel Kökleri Şahkulu İsyanı ve 15 Temmuz” (The historical roots of FETO organization, the Şahkulu Rebellion, and July 15), which is an allusion to the failed coup of the 15th July 2016. Useless to add that there is no connection at all between the Şahkulu movement (not rebellion) and Fethullah Gülen, the notorious leader of the said organization; https://www.marasgundem.com.tr/makale/fetonun-tarihsel-kokleri-sahkulu-isyani-ve-15-temmuz-16277

The war between the Ottoman state and the Safavid Empire had become inevitable, because the unprecedented killings and the Istanbulite anti-Anatolian malignancy caused an even greater reaction among all the populations of Anatolia, Turanian or not. Selim I and Ismail I exchanged several insulting letters prior to the historic Battle of Chaldiran (August 1514) and some of them have been preserved down to our times. They only bear witness to their reciprocal rejection, without however using the colonially-imposed (starting with the 19th c.) false terms ‘Sunni’ and ‘Shia’. About:

Rıza Yıldırım, Turkomans between two empires: the origins of the Qızılbash identity in Anatolia (1447-1514).

Yasin Arslantaş, Depicting the other: Qizilbash image in the 16th century Ottoman historiography

Yusuf Küçükdağ, Measures Taken by the Ottoman State against Shah İsmail’s Attempts to Convert Anatolia to Shia

University of Gaziantep Journal of Social Sciences 7(1):1-17 (2008)

https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/223506

https://www fas nus edu sg/hist/eia/documents_archive/selim.php

Click to access 02selimismail.pdf

https://iranicaonline.org/articles/calderan-battle

https://iranicaonline.org/articles/esmail-i-safawi

https://iranicaonline.org/articles/abul-khayrids-dynasty

https://iranicaonline.org/articles/babor-zahir-al-din

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Shaybani

https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Таварих-и_гузида-йи_нусрат-наме

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shaybanids

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uzbek_Khanate

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khanate_of_Bukhara

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Selim_I

https://tr.wikipedia.org/wiki/I._Selim

https://www.academia.edu/79310004/Masters_of_the_Pen_The_Divans_of_Selimi_and_Muhibbi

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ottoman_dynasty

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ottoman_Empire

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babur

https://tr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babür

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baburnama

https://fa.wikipedia.org/wiki/بابر

https://ar.wikipedia.org/wiki/ظهير_الدين_بابر

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Umar_Shaikh_Mirza_II

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abu_Sa%27id_Mirza

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Mirza

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Miran_Shah

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mughal-Mongol_genealogy

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khanzada_Begum

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Ghazdewan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ismail_I

https://tr.wikipedia.org/wiki/I._İsmail

https://fa.wikipedia.org/wiki/شاه_اسماعیل_یکم

Darius the Great’s Suez Inscriptions: Birth Certificate of the Silk Roads

https://silkroadtexts.wordpress.com/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Marv

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Ghazdewan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khanzada_Begum

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C5%9Eahkulu_rebellion

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C5%9Eahkulu

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schools_of_Islamic_theology#Sh%C4%AB%CA%BFa_schools_of_theology

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Batin_(Islam)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Batiniyya

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Esoteric_interpretation_of_the_Quran

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sufi_cosmology

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sufism

https://ottoman.ahya.net/node/100

https://tr.wikipedia.org/wiki/II._Bayezid

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bayezid_II

https://www.konyapedia.com/makale/3308/sehzade-abdullah-abdullah-bin-bayezit-ii

https://tr.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C5%9Eehzade_%C5%9Eehin%C5%9Fah

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C5%9Eehzade_Ahmet

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C5%9Eehzade_Korkut

https://tr.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C5%9Eehzade_Korkut

https://tr.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C5%9Eehzade_Mahmud_(II._Bayezid%27in_o%C4%9Flu)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Constantinople_Observatory_of_Taqi_ad-Din

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Chaldiran

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C5%9Eehzade_Murad

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Padishah

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caesar_(title)#Ottoman_Empire

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mehmed_the_Conqueror#Conquest_of_Constantinople

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_sultans_of_the_Ottoman_Empire#Names

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amir_al-Mu%27minin

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Custodian_of_the_Two_Holy_Mosques

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ottoman_Caliphate

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caliphate

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taqi_ad-Din_Muhammad_ibn_Ma%27ruf

https://iranicaonline.org/articles/historiography-vi

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Khwandamir

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Habib_al-Siyar

https://www.sid.ir/en/Journal/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=709213

Click to access jaas072001.pdf

https://journals.openedition.org/asiecentrale/2866

https://journals.openedition.org/asiecentrale/499?lang=en

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hatefi

https://iranicaonline.org/articles/golat

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghulat

Comparative evaluation

An objective assessment of the four Turanian rulers whose Iranian education and culture was evident may lead us to devastating conclusions. Finding themselves in different environments, they failed to go beyond the limits of their ‘worlds’. Still, this was imperative for the survival of their respective realms, taking into account what was happening in the Western confines of Asia, namely the pseudo-continent of Europe, which is Asia’s most worthless, most troublesome, and most barbarian peninsula. Consequently, we have to consider them as the initial reason for the collapse of their states, despite the fact that these empires lasted long and fell after 350-400 years. The sole exception is certainly Babur; but he also failed to effectively convey to his offspring and successors the mindset, the predisposition, the attitude, and the ensuing behavior which undeniably helped him transform his Central Asiatic failure into an Indian triumph.

The really embarrassing part of the conclusion is the ascertainment that all four rulers were very civilized, highly cultured, and impressively educated; it goes without saying that I use these terms with the connotation they had at the time, and not the meaning that they have in our fallen, corrupt and putrefied world. They all failed to assess the serious problems that existed in the Islamic World during their lifetime and they proved to be unable to detect the lethal threats that were mounted against their empires and more generally the entire Muslim World. Again, the only exception is Babur, because the time between his conquest of the Sultanate of Delhi and his death is truly brief.

With the exception of Ismail I Safavi (1501-1524), all the rest experienced a rather brief period of reign. Muhammad Shaybani ruled for 10 years (1500-1510); Selim I reigned for only 8 years (1512-1520). And Babur was the sovereign of an empire only for 4.5 years (April 1526-1530). One can truly be astounded with their narrow horizons, naïve approaches to governance, profane understanding of reign, and simplicity in worldview.

Muhammad Shaybani was the living intersection of all things Iranian and Turanian; from his paternal side, he belonged to the lineage of Shayban (also written as Shiban) who was the fifth son of Jochi, the eldest son of Genghis Khan; Jochi was the ancestor of all rulers of the Golden Horde. This means that Muhammad Shaybani was indeed associated and concerned, one way or another, with all the states that came out of the split of the Ulus Jochi (as the Great Empire of the Golden Horde was named at the time), namely the Kazan khanate, the Crimean Khanate, the Qassim Khanate, the Astrakhan khanate and the Nogais.

Muhammad Shaybani was almost 30 years old at the time of the renowned Ugra standoff (1480), when the emperor of the ailing Great Horde failed to impose his dictates on the formerly tributary statelet of Muscovy; Akhmat Khan of the Great Horde and Ivan III of Muscovy, facing one another from the opposite banks of Ugra River, hesitated to cross the river and start fighting, This rather bizarre event is generally considered as the beginning of Muscovy’s independence from the Golden Horde.

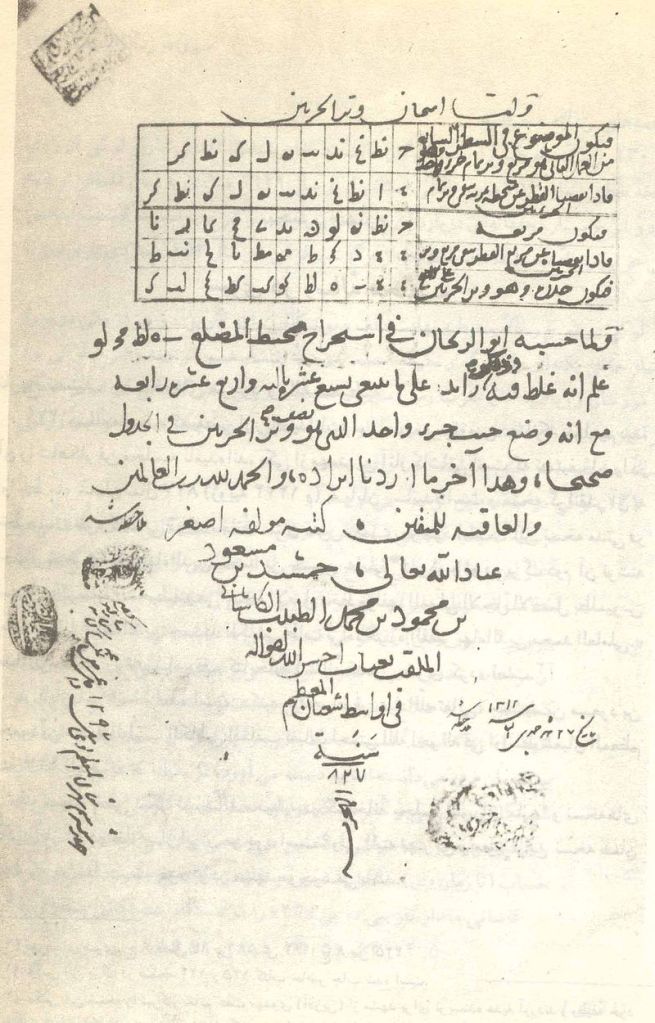

From his maternal side, Muhammad Shaybani was the cousin of Janibek’s son Kasym Khan (reign: 1511-1521), the great Kazakh ruler, who expanded his khanate at the detriment of the Bukhara Khanate. Furthermore, according to the historical treatise “Tavarikh-i guzida-yi nusrat-namah” (Chagatai: تواریخ گزیده نصرتنامه ; Таварих-и гузида-йи нусрат-наме), which was elaborated by Alla Murad Annaboyoglu in the early 16th c. (ed. V. P. Yudin/В. П. Юдин, Alma Ata 1969), Munk Timur, i.e. Muhammad Shaybani’s great-great-great-great grandfather, was married to the daughter of a Turanian descendant of Ismail Samani (849-907; reigned after 892), the founder and first ruler of the Samanid dynasty of Eastern Iran, one of the states that seceded from the Abbasid Caliphate while also recognizing the caliph as the head of all Muslims.

In spite of the aforementioned, briefly presented, background, Muhammad Shaybani remained always a sectarian and tribal ruler. Despite the fact that he was unbiased in his approach to people, although he did not discriminate among Iranians and Turanians (therefore viewing them as one nation), and in spite of the fact that he was truly tolerant in his stance towards Muslim mystics, theologians, members of various tariqas, and followers of different madhhab, he clearly proved to be a treacherous subordinate (to Sultan Ahmed Mirza, a Timurid), a cruel oppressor of the Kazakhs, a disastrous ally to khanate of Moghulistan, a distant and useless friend to Bayezid II, and a consummate plunderer. His poor judgment relied on tribal lineage, family affairs, and petty calculations; this resulted in vindictive deeds, sheer opportunism, and day-to-day governance. He would not be a match for any strong strategist who intended to create an empire. Hating all the Timurids, he defeated Babur several times, but he did not prevent him from establishing one of the world’s greatest empires of all times.

Muhammad Shaybani’s silly head had a well-deserved end; the skull served as a lovely drinking goblet in the hands of Ismail I Safavi. One can even assume that, although it was graciously bejeweled, the goblet was thrown to the ground many times, during those fabulous feasts and banquets of Tabriz – just for fun!

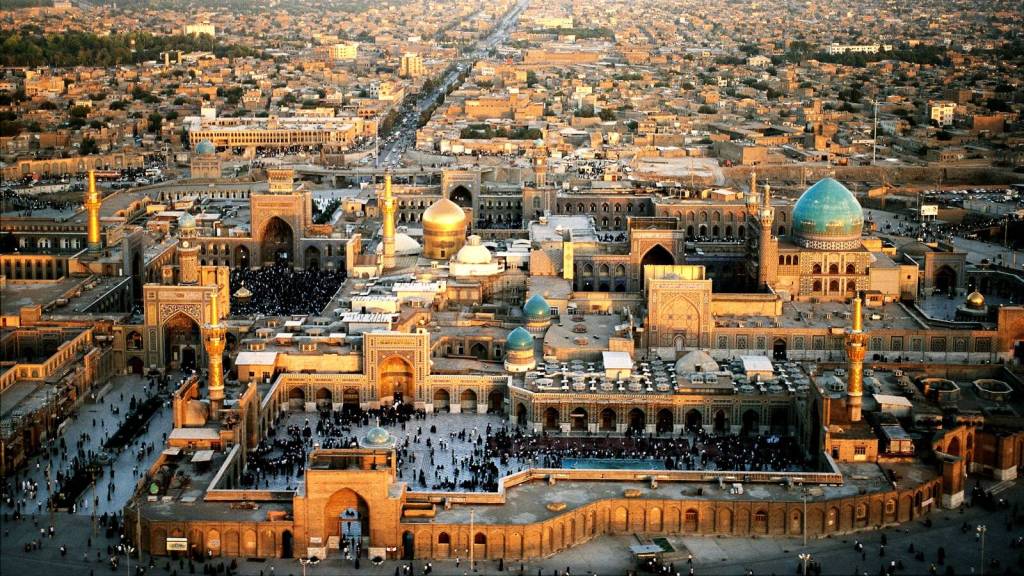

Among these four monarchs, Ismail I Safavi was certainly the best prepared to reign; but he was still acting as a semi-nomad pleased with what was available in nature around him. During his early years in the throne of Tabriz, he used to spend time, camping in the mountains and hunting for several months; there was no urgency to conquer lands and territories. The expansion of his empire was slow and it took the form of a joyful endeavor instead of a serious state affair, scrupulous programming or a major expansion stratagem. There were certainly many wars, notably against the Shirvan kingdom (in part of today’s Azerbaijan), the Kartli and Kakheti kingdoms of Georgia that became vassal states, and the Aq-Qoyunlu nomadic sultanate that was entirely eclipsed, but there was no methodical undertaking in this regard. Not a care in the world!

Within few years, the empire of Ismail I Safavi replaced the Aq-Qoyunlu tribal confederacy, but there were no second thoughts, no back thoughts, and no serious observations, let alone monitoring, of developments, state affairs, and relations among neighboring states. To offer an example, not one Iranian magistrate in the court of Ismail I Safavi took note that two Kakheti Georgian embassies had been dispatched by Alexander I to Ivan III of Muscovy (in 1483 and 1491) as soon as the tiny statelet stopped paying tribute to the Golden Horde.

Ismail I Safavi and his spiritual brethren, namely the members of the most ancient and most venerable Safavid Order and the combatants of the Qizilbash contingent, acted out of free will and spiritual illumination. They did not need to even name their empire; at the beginning; the structures of state were rudimentary, and there was no bureaucracy at all. Ismail I Safavid was indeed closer to Cyrus the Great than Shapur I was. Living the epic moments superbly narrated by Ferdowsi, Nezami Ganjavi and others, performing the spiritual exercises of Saif ad-Din Ardabili, and staying in cities only during the cold winter months of the Iranian plateau, they gave the impression that wars consisted merely in short break times of a peaceful eternity that they enjoyed. Fearless to die in battle, knowledgeable about the Hereafter, and devoted in their vow, they were less envious, possessive and worldly than most of the soldiers of their time. There was no need for a rational plan for war, because this is genuinely evil; there was impulse for war instead – which is genuinely human.

This situation may perhaps appear as confusing and unpromising to many people, but it is not. Of course, it is normal for a mystical fighter to believe that due to the synergy between his soul and body, he is indomitable and invincible; this conviction is basically correct and true. However, it takes a very high degree of moral discipline and of self-restraint for the spiritual potency and the inherent impulse of the fighter to be exacted and exerted. Quite unfortunately, Ismail I Safavi’s spiritual master and mentor, Hossein Beg Laleh Shamlu, tolerated a great degree of self-gratification, self-complacency, and even exuberance; he was lenient with the rising emperor, his brethren, and his guards. This did not bode well for the ruler, his army, and his empire. Compromised moral is tantamount to weakened spirituality and emollient attitude conditions human integrity.

This explains perfectly well why, after his defeat in Chaldiran (1514), Ismail I Safavi collapsed and lived the rest of his life ashamed, in sadness, despair, lamentation and uncontrollable alcoholism; in reality, there was nothing to be sad for. During the battle, the Iranians were about to mark a thunderous victory, being provenly better trained to fight; the Ottomans won only because they started using gunpowder artillery that the Iranians did not have. Even worse, the Ottoman army was about to be cut to two pieces, because the Janissaries did not accept to fight against and kill their Muslim brethren. Actually, the Ottoman soldiers who used the cannons that they had transported with greatly difficulty also murdered Ottoman Janissaries. However, a mystical fighter with compromised moral and self-indulgent attitude certainly collapses after a defeat; quite contrarily, a mystic strongly experienced in ascetic self-denial never feels sorrow, frustration and depression – ever after an extreme adversity.

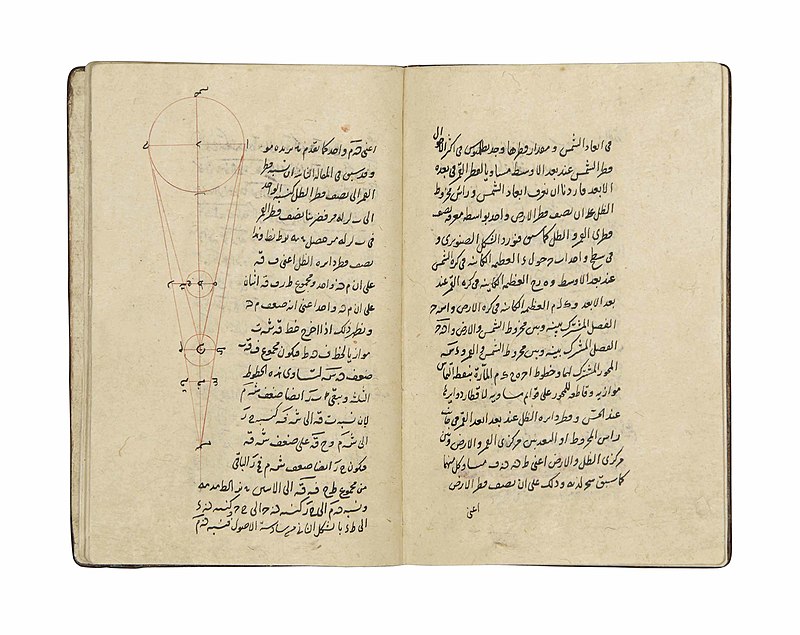

Having to fight against monstrous criminals, rancorous establishments, bloodthirsty rulers, rancorous enemies, inhumanely cruel soldiers, professional serial killers, and greedy armies that sailed off to intentionally perpetrate genocide in Mexico and to circumvent Africa by sailing around the Cape of Good Hope, the Safavid elite was rather living in a dream that turned out to become a nightmare for Iran and for the almost the entire world. Iran had always been a major empire with long maritime tradition; Achaemenid Iran is credited with the merge of several earlier regional trade routes that had existed for millennia; this was due to the unmatched, royal administrative genius of Darius I the Great (522-486 BCE).

Darius the Great’s contribution to the emergence of the east-west trade network was twofold: a) the establishment of the Royal Iranian Road and b) the circumnavigation of the Arabian Peninsula and the direct maritime connection of the Mediterranean and the Red Sea with the Persian Gulf. Oman was always an Iranian satrapy; and during the Sassanid times, Iran invaded also Yemen, which was a focal land for the world trade between East and West. However, this background was entirely lost and the Safavid elite did not care at all about the maritime presence and strength of their empire despite the fact that in the beginning of the 16th c., Iranians still controlled an important part of the commerce between East and West, having always been an important constituent of the Islamic times’ navigation and trade. But for all the people around Ismail I Safavi, treasures were to be mainly collected from lands conquered and cities pillaged.

For the case of Ismail I Safavi, one is however tempted to think that the historical heritage itself rather than the various individuals and the ruling elite resurrected the Iranian Empire under the Safavid dynasty. The spiritual exercises of the Safavid Order, their ruminations, their cordial illuminations, and their angelic invocations seem to have electrified the Soul of Iran as incantated by Ferdowsi; but their impious self-indulgence confused the serenity of their souls and made it sure that their pledge was predestined to doom.

Selim I shared the same ideas as Ismail I Safavi and Muhammad Shaybani about a state’s chances to acquire wealth; this was not due to cultural tradition (as in Iran) or to geomorphological impact (as in Central Asia). The state that Selim I -through plots, family disloyalty, treason, and shameful banditry- managed to put under control stretched from Central Anatolia to Belgrade; this had been the usual, typical domain of the Constantinopolitan βασιλείς (basileis; emperors) from the 7th to the 12th c. The official name of the state was invariably ‘Eastern Roman Empire’, and this was the will of all the successors of Mehmet II. But quite unfortunately, the ill-fated Ottoman Sultanate was controlled by a criminal, pseudo-Muslim family, which was manipulated by idiotic theologians, sectarian sheikhs, and a bogus-Islamic authority, the sheikh-ul-Islam (also written as Shaykh al-Islam). The sultans wanted, quite absurdly, to represent the Eastern Roman imperial tradition, while remaining the petty warriors (غازى; ghazi), who relied on worthless and unnecessary razzias (غزية), i.e. military expeditions of greedy barbarians; this meant that they were a 14th c. state in a 16th c. world; this situation could not possibly have a successful exit.

The immediate descendants of Mehmet II continued ruling their realm in a most ineffective manner that included very contradictory elements, practices, concepts and procedures, which produced endless tensions. On one side, the devshirme (دوشیرمه; devshirme; lit. ‘collecting’), i.e. child levy, and the janissary infantry elite (یڭیچری; yeniçeri) gave the Ottoman sultan (and, after 1453, emperor) the real tools to create a formidable empire similar to that of Justinian I. But on the other side, the obscure, nefarious and ominous presence of a body of execrable theologians and their increasing, onerous and catastrophic impact on the sultan gradually turned the Ottoman sultanate to a sort of Papo-Caesarist realm, whereas for the Eastern Roman Empire (of which the Ottomans wanted to make their state the living continuity) the Caesaropapist model of rule had to be the sole, paramount and permanent concept of imperial order.

The existing anachronistic elements, the tensions ensued from the contradictory dynamics, the ruinous hatred unleashed by the blind, dogmatic and cruel sheikhs and sheikh-ul-islams, and the vindictive stance of many sultans (as well as of other members of the Ottoman family) triggered unprecedented reactions. In their outright majority, the populations, either Christian or Muslim, reviled the cursed state of the Ottoman family (دولت عليه عثمانیه; Devlet-i Aliye-i Osmaniye), whereas the wretched family in a vicious and most anti-Islamic manner disrespected the humans that God had entrusted to them. This situation led to real worsening of the living conditions, sheer deterioration of the state structures, and grave decrease of government effectiveness.

The Ottoman Sultanate never managed to acquire a well-structured administration; that’s why it was never a strong empire that could methodically elaborate a program of expansion or Reconquista. Islamic spirituality was besmirched, attacked and later prohibited; the worthless Ottoman bureaucracy was a burden; the wars declared against neighboring empires were due to sectarian or arbitrary motives; and the only sound element in the empire was the janissary elite.

A mere comparison of the Roman and the Ottoman possessions in Africa helps everyone realize how absurd, precarious and inconsequential the rule of the Ottoman sultans was. On the Black Continent, the Ottomans controlled an area more sizeable than the largest Roman dominions there. The Romans never managed to advance successfully south of Egypt and to conquer the Cushitic (i.e. Ancient Ethiopian) Kingdom of Meroe in today’s Sudan; but they controlled the African North up to the coasts of today’s Morocco.

The Ottomans invaded Egypt (1516-1517) to disband the Mamluk state, and then they progressively extended their rule over the entire coast of North Africa, thus including Algiers (1518), Benghazi (1521), Tripoli (1551) and Tunis (1574) in their domain; the Ottomans were invited and acclaimed by the indigenous populations that were mostly Muslim (only according to Western colonial propaganda, the Ottomans ‘colonized’ North Africa), and until the time these lands were incorporated into the Caliphate, the Ottoman Emperor was acknowledged as the caliph – which already made of these lands real dependencies of the Constantinopolitan Muslim ruler. Under Suleiman the Magnificent (1554) and Murat III (1576), two Ottoman military expeditions were undertaken in Morocco, ending with the capture of Fez.

In Eastern Africa, the Ottomans sent detachments and corsairs to defend the Somalis against the Portuguese (in the 1520s-1540s), having excellent relations with all the Somali sultanates, notably Adal and the Ajuuraan Empire. In fact, by recognizing the caliph at Constantinople and by mentioning his name first in the Friday prayer, all Muslim African sultanates and emirates recognized the Ottoman Caliphate, thus becoming effectively mere dependencies of the Caliphate. That’s why there was no real need for an Ottoman invasion of the Western Africa, Sahara (the Songhai, Mali, Hausa-Zaria, Kanem-Bornu, Wadai, Funj, Darfur, and other realms), and Eastern Africa. Located south of the Mısır eyaleti (as the province of Egypt was named in Ottoman Turkish), the Habeş eyaleti (i.e. the province of Abyssinia) comprised the coastal lands of today’s Sudan, Eritrea, Djibouti, and parts of today’s Somalia and Ethiopia). The Adal Somali sultanate shared therefore borders with the Ottoman Empire.

But exactly because of the highly de-centralized condition of the Muslim African world, it was totally impossible for them to establish a major, functional force ready to repel colonial attacks. Even worse, the Ottoman dominions in North Africa never became a serious matter of governmental concern and there was never a real effort to organize, systematize and standardize the integration of the African vilayets into the Ottoman state. Certainly, the Ottoman Empire controlled vast territories in Africa; but because of the aforementioned problems, these lands were a burden rather than an advantage and an asset. In this regard, Selim I’s attack against the Mamluk state and his subsequent invasion of Syria, Palestine, Arabia and Egypt, after the victory he marked over Ismail I Safavi in Chaldiran, proved to be a complete waste of the Ottoman military resources.

Bayezid II’s disloyal son was not prepared to become an emperor and that’s why he was a miserable opportunist without a clue of strategy; he could not understand what truly makes an empire strong, wealthy and sustainable. With respect to the expansion of a state, he did not know which lands are necessary and which are not; even worse, he did not observe -let alone study- patterns and models of expansion from the History of the Islamic Caliphates and Empires.

Selim I was a blind, indoctrinated idiot, who -after his victory in Chaldiran- lost the unique opportunity to promptly invade Iran, merge the two Turanian and Iranian empires, and then attack the Sultanate of Delhi. I have however to admit that he did not have the correct education, the shrewd mindset, and the accurate perception of the reality to possibly think strategically and act accordingly. The Iranian plateau and the valleys of Hindustan (India) and Bengal were far more important than the sands of Arabia and the waters of the Nile.

Had he attempted to establish one empire from Danube to Ganges, he would have followed the example of Timur (Tamerlane); at the same time, he would have created a uniquely wealthy empire able to possess the inexorable resources and the technical infrastructure needed to oppose and defeat the Western colonial kingdoms.

Babur makes Humayun his successor (1530); miniature from a manuscript of the Akbarnameh (created ca. 1602-3)

Babur treated by doctors during a serious illness, in 1498; while recuperating, Babur had a relapse and his condition became critical; for four days he could only take water dribbled into his mouth from a piece of cotton, and for several days he could barely speak.

In his Baburnama (Book of Babur), the founder of the Mughal Empire describes his struggle first to assert and defend his claim to the throne of Samarkand and the region of the Fergana Valley. After being driven out of Samarkand in 1501, he sought to create his headquarters in Kabul and then in northern India in Delhi. In this miniature from a manuscript of the Baburnama, Babur meets Sultan Ali Mirza near Samarqand.

Scene from Babur’s wars; from a miniature of the Farsi edition of Baburnama (translation by the Mughal courtier Abdul Rahīm in AH 998, i.e. 1589-90)

Babur from the miniature of manuscript of Baburnama currently in the Museum of Oriental Art (Государственный музей Востока), Moscow

Vasily III, ruler of Muscovy (1479-1533; reigned after 1505), son of Ivan III and Sophia Palaiologina, receives the ambassador from Babur; miniature from the 19th volume of the Illustrated Chronicle of Ivan the Terrible (Лицевой летописный свод Ивана Грозного)

The Mausoleum of Babur (Bagh-e Babur, i.e. Babur Gardens) in Kabul

Khusrau shah swearing loyalty to Babur; miniature from the Baburnama copy in Moscow

Babur receiving Baqi Beg Chaghaniyani, a Turkistani Qipchaq, in his encampment on the banks of the Amu Darya (Oxus); Baqi was a loyal supporter of Babur contrarily to his brother Khusraw shah, whom Baqi brought to pledge allegiance; however, at a later moment, Khusraw shah proved to be a traitor once more. Miniature from a manuscript now in the British Library (Or. 3714, f. 35v); it was painted by the Mughal artist Bhem Gujarati.

Miniature from a Baburnama manuscript now in the National Museum, New Delhi; squirrels, a peacock and peahen, demoiselle cranes and fishes

Babur was exempt of sectarian ideas, tribal mentality, and worthless theological prescriptions; of the Western colonial powers he had minimal knowledge, if any. Deep in his heart and mind he had apparently the wish and the dream to prove himself worthy of his glorious past; for this reason, he needed to establish himself somewhere, i.e. to set up the headquarters of his forthcoming empire. Samarqand was an ideal location; but there he failed repeatedly. Babur’s life was not that of a great emperor, because prior to the invasion of the Delhi Sultanate, his realm was always small and constantly under attack.

Continuously moving from place to place with his few but loyal and devout soldiers, Babur was however an indomitable adventurer, an indefatigable soldier, an excellent tactician, and a great strategist. The greatness of the Mughal Empire, which was far wealthier than the Ottoman Empire, Iran, Russia, Holland, England and even Louis XIV’s France, was basically due to its founder Babur. As it is known, he died rather young (at 47). If he had lived as long as his great ancestor Tamerlane (69), the History of Asia would have certainly been markedly different.

Great rulers are those who prepare well their successors; to do so, they have to endlessly convey to their heirs their way of thinking, their approach to facts, their reaction to developments, their world perception and worldview, and -last but not the least- their method of governance. This is often a long enduring process; it is not always sure that the elder son of a ruler is fit to it. For this reason, we often observe a ruler’s predilection for his second or third son. For Babur this dilemma did not exist; Humayun (همایون/lit. ‘auspicious’ in Farsi; born as Mirza Nasir-ud-Din Muhammad; 1508-1556) was his firstborn (being also son to Babur’s favorite wife Maham Begum), and he proved to be a loyal, shrewd and very knowledgeable heir.

Babur apparently imparted his first son with many of his crucial personal traits and great abilities, notably his mobility, agility, flexibility and adaptability. That’s why Humayun managed to survive, although he was inexperienced at the beginning of his reign, when he faced many challenges, particularly from his half-brother Kamran Mirza and from Sher Shah Suri, a villainous and heinous scoundrel who set up a divisive but temporary rule. All the same, Humayun recaptured his empire with the help of Ismail I Safavi’s son Shah Tahmasp I (طهماسب; 1514-1576), and later consolidated and even expanded his realm. About:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Humayun

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kamran_Mirza

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tahmasp_I

However, Babur did not achieve to pass onto his son and successor a superb quality that was the top trait of Timur’s and Genghis Khan’s idiosyncrasy; this consists in a rare moral expertise and spiritual dexterity to invariably disdain and undervalue material achievements of one’s own and to thus infallibly maintain the original impulse toward a great vision permanently alive. Genghis Khan and Timur were indelibly motivated by their vision to unite the world; Babur was stimulated by his first target to re-establish the great empire of his ancestors, but he did not stay long on the throne of Agra (1526-1530).

With him died the vision of a universal empire. Humayun had to fight all his life long to eliminate threats and challenges and, when everything was put under control, he did not enjoy his throne more than few months before dying at 48, due to an accident. When Akbar I (أكبر; born Abu’l-Fath Jalal-ud-din Muhammad; 1542-1605; reigned after 1556) was crowned, very little was left from the original vision of his grandfather, Babur. Akbar I expanded greatly his realm and, after a certain moment, he shifted his interest to the North with the intention to extend his borders up to the ancestral lands in Central Asia; but by the end of the 16th c., it had become very clear to Akbar I that it was impossible to incorporate Samarqand and the Ferghana Valley to his empire.

To the early instability of the Mughal Empire and to Akbar I’s effort to expand in Central Asia testify the incessant changes of the Mughal capital: Agra 1526-1540, Agra 1555-1571, Fatehpur Sikri 1571-1585, Lahore 1586-1598 (reflecting Akbar I’s move to the North), Agra 1598-1648 and Delhi 1648-1857. In fact, Akbar’s death marks the end of every Central Asiatic venture of the Mughal rulers.

The Mughal Empire expanded greatly across the Asiatic South, notably the Deccan; it impacted considerably the formation of Muslim sultanates in Southeastern Asia and the islands of today’s Indonesia. All the same, the Gurkanian (گورکانیان; lit. ‘the sons-in law’), as the Iranians called the Mughal emperors due to an old Turanian tradition, only corroborated the unchangeable verdict of History, namely that from Central Asia, Iran, Mesopotamia and Anatolia great military expeditions to faraway lands have often been and can actually be undertaken successfully; but no ruler has ever launched a campaign and a conquest of major parts of Asia, starting from the Valley of Indus and the Valley of Ganges. (The same is also valid for the Yellow River and the Yangtze River valleys.)