By Prof. Muhammet Şemsettin Gözübüyükoğlu (Muhammad Shamsaddin Megalommatis)

Pre-publication of chapter XXIII of my forthcoming book “Turkey is Iran and Iran is Turkey – 2500 Years of indivisible Turanian – Iranian Civilization distorted and estranged by Anglo-French Orientalists”; chapter XXIII constitutes the Part Nine (Fallacies about the Golden Era of the Islamic Civilization). The book is made of 12 parts and 33 chapters.

—————————————————-

Known rather through his cognomen (‘Paradisiacal’) and his kunya (teknonym: Abu’l Qassem, i.e. ‘father of Qassem’), Ferdowsi was born (ca. 940) in Tus (Khorasan, NE Iran) around the time Muhammad ibn al-Askari, son of Hasan al-Askari and 12th Imam, went into his Major Occultation (941). The apocalyptic eschatological fascination of those days is explicitly shown in Ferdowsi’s own name, because the quest for the Paradise is the epitome of every reliable Messianism (: Soteriology) and Eschatology.

Ferdowsi is a worldwide unique case of highly venerated poet whose work is absolutely immense and whose known details of life are incredibly minimal; although he was historically referred to as the leading epic poet, erudite sage, and unsurpassed master of Farsi (and there have been several historical biographies of him), we don’t know even his real name. Judging from his son’s name, Ferdowsi (940-1020) was a Muslim, but there stop all the important biographical details that we know. In fact, Ferdowsi’s life is enveloped in mystery and legend similarly with the contents of his monumental and sublime epic; we know however that he had a great Turanian sponsor: the formidable Conqueror and Emperor Mahmud Ghaznavi (971-1030; the founder of the Ghaznavid dynasty), who invaded the Indus Valley, Punjab and the Ganges Valley, unifying territories that stretched between the Caspian Sea and today’s Bangladesh.

Ferdowsi mausoleum, Tus – Iran

Ferdowsi’s unsurpassed masterpiece, the Shahnameh (: the Book of the Kings) is the world’s largest epic totaling more than 100000 (one hundred thousand) verses. In terms of Iranian Literature, it was not the first epic composed under this title. Thanks to his historical biographies, we know that Ferdowsi started the composition of the enormous opus in 977, initially viewing it as the completion of a similar effort earlier undertaken by another Iranian poet, Abu Mansur Daqiqi, who did not have the chance to advance his Shahnameh much before being assassinated. However, Ferdowsi’s epic differs greatly from all the other Shahnameh epic poems or prose compositions in many ways; although similar narratives have been attested in other Iranian and Islamic epics, Ferdowsi places his heroes in an atemporal field of semiotics whereby they function as symbols of spiritual ideas, moral principles, and eternal values.

Was Ferdowsi a ‘Sunni’ or a ‘Shia’? The question sounds irrelevant; although it is evident that he was a Muslim and a strong monotheist (which also applies to several forms of pre-Islamic Iranian religions), Ferdowsi does not contain the slightest portion of reference to the Early Islamic History into his legendary opus.

Is pre-Islamic Iranian-Turanian History reflected in Ferdowsi’s epic? In a way, yes! But it is an ahistorical reference to a series of dynasties that modern Iranologists, philologists, specialists in Comparative Literature, historians and historians of religions, experts in Mysticism Studies and Symbolism try in vain to accommodate within the scholarly known frame of the Achaemenid, Arsacid and Sassanid dynasties. This is however quite impossible a task to carry out; and Ferdowsi is the only reason for this. Although there is not a single indication that Ferdowsi divided his masterpiece into ‘periods’, the entire Shahnameh is divided, on the basis of typical literary analysis, into three sections: mythical age, heroic age, and historical age.

As per this – absolutely wrong – categorization, all the aforementioned pre-Islamic Iranian dynasties belong to the third section (historical age). But more than two thirds of the enormous epic’s verses are dedicated to the narration of episodes of the so-called ‘heroic age’. An analysis of Shahnameh goes beyond the scope of the present book, but with the above brief description I wanted to point out that Ferdowsi mainly focused on pre-Achaemenid eras and that his intention was to illuminate the spiritual ideas and the human valor that predestined historical Iran-Turan to be what we know through regular historical documentation that it was. Despite the numerous distortive presentations and worthless analyses, if one stays close to Ferdowsi’s verses, one concludes easily that, as per the illustrious poet and mystic, Iran-Turan constitutes an indivisible world.

Was Ferdowsi a Persian or a Turanian? This question in and by itself reveals total ignorance of Iranian and Turanian History, Culture and Civilization. The undisputed and definitely unequaled mastership of Farsi to which the majestic composition of Shahnameh bears witness does not make of Ferdowsi a Persian. Across the ages, many Turanians excelled in Persian poetry. Ferdowsi’s origin from Khorasan (a region traditionally inhabited by Turanians and Persians alike) and his close relationship with the great Turanian Emperor Mahmud Ghaznavi show that it is quite plausible that Ferdowsi was a Turanian. Mahmud Ghaznavi vanquished the Samanid state (995-999) pretty much like the Seljuk Turks had destroyed the Buyids half a century later. Consequently, we can conclude that Ferdowsi ostensibly sided with Turanian institutions and rulers against Persian states and kings.

There are also some other indicators that must be taken into consideration, as regards Ferdowsi’s identity: although his legendary narratives reflect the foremost values of the Achaemenid Civilization and represent the Zoroastrian conceptualization of the Universe, the contents of Shahnameh do not stringently correspond to the world of Parsis, namely those among the Sassanid times’ Persians who managed to escape the Islamic onslaught and survived in Iran and in India, preserving a posterior form of Mazdeism (and Zoroastrianism) that we presently call ‘Parsism’. Several PhD-level dissertations can be elaborated to properly demonstrate that on many critical issues Ferdowsi’s viewpoint on the pre-Islamic Iran and the Parsis’ traditions pertaining to the Sassanid (and earlier) past differ greatly.

In Shahnameh, one cannot find the slightest support for the Parsi faith, let alone of the Parsis’ anti-Islamic feelings. There is not a single sign that Ferdowsi saw his grand opus as an Iranian ‘comeback’ (let alone ‘revenge’), as an instigation of pre-Islamic Iranian ‘patriotism’ among Iranian Muslims or as anti-Islamic fascination and mobilization. On the contrary, throughout Shahnameh, there are incessant references to Turanian gallantry and passion, bravery and confusion, unity and division, crime and punishment, discipline and order, mysticism and divination, honesty and treachery, clarity and confusion.

The Iranian – Turanian epic presents a magnificent equilibrium among all tendencies and characters, trends and exploits, attempts and regrets. Shahnameh attains a spherical perfection, contains no pointless element, locates all elements in their correct place whereby everything meets its reverse reflection and all spirits are accompanied by their opposites. All this is put in perfect Farsi, in lines of 22 syllables, in rhyming couplets (masnaviyat), and in metre 1.1.11.

Where does Ferdowsi stand among his time’s mystics, orders, kings and warriors, erudite scholars and theological jurists?

Was he close to late Sassanid Zervanism? Certainly not as much as Tabari, a fully accredited Islamic exegete and theologian, founder of a major madhhab, and the Islamic world’s supreme historian! Tabari dedicated the introductory chapter of his voluminous History to a theoretical analysis of the Time (: Zervan or Zurvan, a late Mithraic figure that was the central god of a late branch of Mithraists). But Ferdowsi started his epic with Keyumars (Gayomard of the late Zoroastrian texts), the first man and first king (Pishdad dynasty); this approach makes of royalty the first human virtue.

Was Ferdowsi close to the late Sassanid followers of Gayomard? Not quite! His focus on the recapitulation of themes related to heroic combats gives us the impression that Ferdowsi envisioned a dynamic universe in which Cosmogony and Eschatology consisted in an indivisible entity of spiritual and material order based on a permanent movement back and forth between Being and Becoming.

From all the major groups of early Muslims and from all the followers of then extant Iranian religions, the Khurramites, the Parsis, the Manichaeans, the Mazdakists, the so-called Twelver Shia, the Isma’ilis, between the Mazdeists and all the rest, Ferdowsi seems to be equidistant.

The same attitude appears in the Shahnameh; between the Turanian Afrasiab and the Iranians Siyavash and Kay Khosrow, Ferdowsi pursues a narrative that does not favor any of the combatants, while presenting brave deeds and mythical facts as the straight result of the great legendary heroes’ spiritual choices and divine providence.

In fact, Ferdowsi is to be found at cosmic distance from all his contemporaneous mystics, poets, erudite polymaths, historians, scholars and theologians. Next to him, all the rest appear infinitesimal. That’s why we can safely claim that within the wider context of Islamic Civilization across Eurasia only Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh proved to be as influential a book as the Quran. The great epic impacted all the Islamic nations, ethno-linguistic groups, mystical orders, intellectuals, poets, authors, and artists so irrevocably that, from the beginning of the 11th c. onwards, it would perhaps be more accurate, instead of speaking of Iranians and Turanians, to start referring to them as Ferdowsians. About:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferdowsi

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shahnameh

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Persian_metres

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahmud_of_Ghazni

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghaznavids

http://materiaislamica.com/index.php/The_Great_Ghaznavid_Dynasty_(c._962%E2%80%94c._1186)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Keyumars

https://iranicaonline.org/articles/gayomard

https://karakalpak-karakalpakstan.blogspot.com/2015/05/the-zoroastrian-creation-story-mizdakhan.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pishdadian_dynasty

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kayanian_dynasty

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Afrasiab

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siy%C3%A2vash

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kay_Khosrow

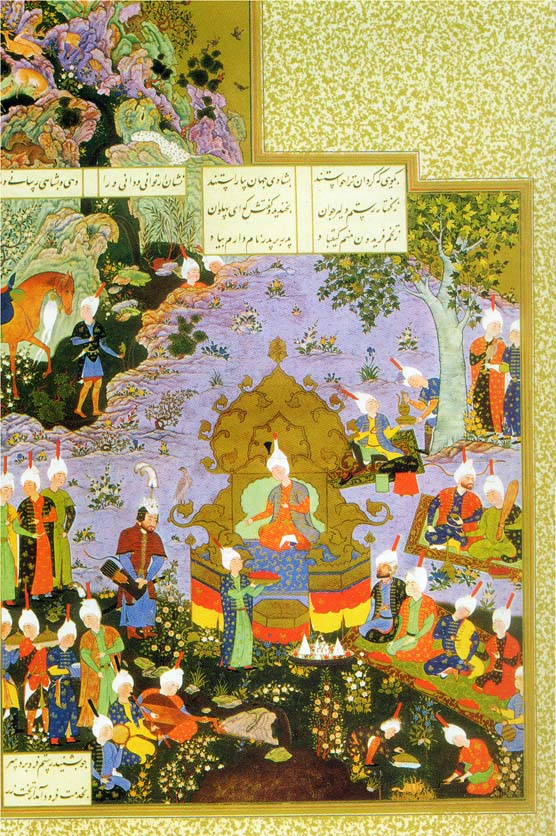

Kay Qobad (Kay Kawad) on his throne; a leading figure of the Kayanid dynasty that was transcendentally constructed by Ferdowsi

In fact, one cannot speak about the Seljuk Turks, before briefly presenting Ferdowsi’s Cosmogony within the Islamic world. This is so because the Seljuk dynasty, along with the Ghaznavids, proved to be the first and the most enthusiastic adepts and supporters of the heroic worldview narrated by Ferdowsi, of the spiritual ideas revealed in Shahnameh, and of the moral values respected by the great heroes of the legendary, atemporal and apocalyptic Pishdadian and Kayanian dynasties. In fact, only this phenomenon, i.e. the Ghaznavids’ and the Seljuk Turks’ wholehearted acceptance and overwhelming promotion of the Universe as reassessed by Ferdowsi, makes of the grand master of Farsi Literature the national poet of all Turanians.

Quite contrarily to the historical facts, the criminal Western Orientalists depict a terribly tarnished and viciously distorted image of this reality; as per their false and nonsensical interpretations, the Seljuk Turks accepted Islam through Persian culture. This is as idiotic as an eventual, irrelevant assumption according to which a (fully hypothetical) educational jury was supposedly awaiting at the northeastern Iranian borders for the Seljuk Turks to come, and then upon their arrival, they told them: “pass your Ferdowsi exam, and come-in”! So pathetic and ludicrous is the Western Orientalist approach to the topic! Things did not happen that way, and this reality shows that it is absolutely absurd and utterly calamitous for any Turkic and Iranian nation to accept the presence of Anglo-American institutions in their territories or to allow their nationals to study in Western universities or even to visit West European, North American, and Oceanian countries.

The heroic, legendary, cosmological and eschatological order revealed by Ferdowsi in his Shahnameh was the basic oral culture of all Turanians and Iranians, Persians included, for millennia. Simply, this cultural background was not (and could not be) the religious dogma of Zoroastrianism (and of its subsequent forms, i.e. Arsacid Zendism and Sassanid Mazdeism) as attested in the holy texts of that religion and in the imperial inscriptions of the faithful Kings of Kings.

The fallacy of Modern Western Humanities, as developed in the racist, colonial, criminal pseudo-universities of Western Europe and North America, is due to the paranoid (but intentionally implemented) method of compartmentalizing the historical truth and the exploration thereof; this occurs in total contradiction to the universal, comprehensive and holistic approach and method (of viewing and examining the historical truth) that prevailed among all the great historical civilizations (whereby there was no compartmentalization). This vicious method leads colonial historiographers to the distortive division of topics into separate ‘academic fields’: history, archaeology, philology (‘literature’), linguistics, history of religions, ethnography and social anthropology, philosophy, history of arts, history of sciences, architecture, and so on. Consequently, this makes researchers separate their various study topics between “written cultures” and “oral cultures”; but by so doing, they totally misperceive and misrepresent entire historical periods.

As a matter of fact, Ferdowsi did not ‘invent’ (or ‘envision’ or ‘conceive’ or ‘devise’ or ‘create’) his narratives; he only managed to compose them in an incomparably genuine and superior poetic manner. All the terms, names and ideas of Shahnameh’s stories antedate Ferdowsi for about 1500 years – to say the least; this is something that all Orientalists accept. But they fail to see that these terms, names, ideas and stories constituted the oral culture of all the Iranians and the Turanians long before the heliocentric fallacy of Mithras was first propagated among them in the first half of the first pre-Christian millennium. Ferdowsi wrote down this millennia-long Turanian and Iranian oral anti-Mithraic cultural tradition in a literarily majestic manner. And by doing so, he did not ‘give’ the Seljuk Turks their culture (which was already theirs and their ancestors’), but the wings that they needed to conquer the world and implement their millennia long values and virtues as reinstated in the Quran and reinterpreted in the Shahnameh.

Of course, there is a reason the colonial historiography appears to have some success in plunging readers into deceitful schemes, distortive narratives, and nonexistent popups; if you are naïve enough to believe that the Seljuk Turks came from the North Pole or the Moon, then you will certainly accept the fallacy of the so-called Seljuk acculturation in Iran, and you will start believing the nonsense of the Turanian nations’ ‘persianization’. But the Seljuk Turks were neither in the North Pole nor in the Moon! In fact, they had been -for several centuries- just on the other side of the Islamic Caliphate’s northeastern border. And for cultures, for nations, for faiths, and for civilizations, there are no borders; even more importantly, borders do not apply to oral cultures.

Even more absurdly, “border historiography” cannot exist across the Silk Road; by ‘stopping’ their premeditated and therefore fallacious description of historical facts at the borders of the various modern states, the criminal Western pseudo-historians intentionally implement their evil political axiom ‘divide et impera’ throughout Humanities. This is the way most of the people worldwide have been deceived in this regard.

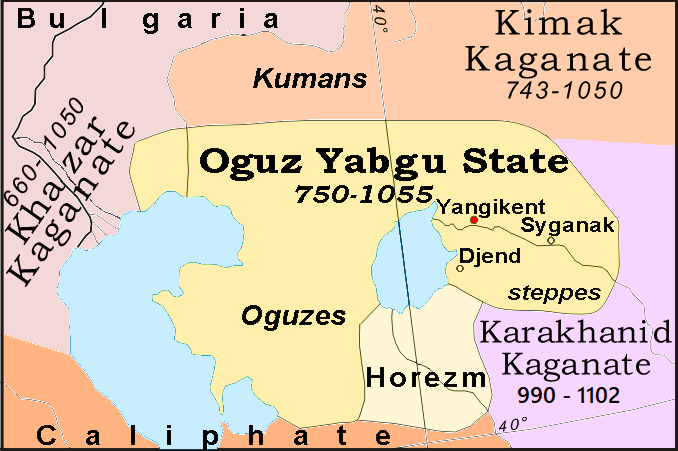

For several centuries, the ancestors of the Seljuk Turks lived within the wider Yabyu (English: Yabghu) territory within the land of the Oguz/Oghuz (Oğuz) nomads’ state. Its location stretched across vast territories of the modern states of Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and (to smaller extent) Uzbekistan. Yabyu spanned east of the Khazar Khaganate (or Khanate), between the Caspian Sea and Aral Lake, and north of the border of the Islamic Caliphate. The forefather of the Seljuk Turks was a formidable Oghuz combatant named Seljuk, who served also in the Khazar army, before clashing with other Oghuz warriors, migrating to southeast (around the year 980), and settling in Transoxiana (Arabic: Mawarannahr / ماوراءالنهر), next to Syr Darya (Iaxartes) river. At that original stage, the ‘Seljuk Turks’ (i.e. the family of Seljuk) were less than 1000 people in total.

Seljuk made an alliance with the Samanids (a mainly Persian kingdom) and fought against the Kara-Khanids, a Turanian Khaganate, mainly known as the House of Afrasiab (آل افراسیاب / which means that they were named (as early as the 9th c.; so before Ferdowsi) after the most important Turanian hero of Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh. The development was not good for the Seljuk family, and Seljuk’s grandsons Tughril and Chaghri had to further migrate (ca. 1040) to the South (Khorasan). The son of Mahmud Ghaznavi, Mas’ud I of Ghazni, tried to prevent them from advancing, and the battle of Dandanaqan (near Merv in today’s Turkmenistan) opened the way for the Seljuk rise. Tughril’s and Chaghri’s victory (1040) was tantamount to Seljuk prevalence in Khorasan. Ten years later (1050), Tughril invaded Isfahan and established the Great Seljuk Empire.

However, only to prove the inalienable, indissoluble, and indelible nature of the Turanian–Iranian civilization and identity, the early Seljuk success across the Iranian plateau would have no historical continuity and impact without the astounding contribution of a Persian original: Abu Ali Hasan ibn Ali Tusi, who is rather known through his incredible title ‘Nizam al Mulk’ (:”Systems of Royal Governance”). Nizam al Mulk (1018-1092) was born two years before Ferdowsi died, but his inclination and genius covered a totally different field than that of the greatest epic poet of World History. Originating from Khorasan, Abu Ali Hasan ibn Ali Tusi left his position at Ghazni, the capital of the Turanian Ghaznavid Empire and entered the service of the Seljuk Turks (1043); there he was entrusted, among other tasks, with the education of Muhammad bin Dawud Chaghri (mainly known as Alp Arslan), i.e. the son of Chaghri and nephew of Tughril, the founding sultans of the Seljuk empire.

The assassination of Nizam al Mulk

Consequently, the rise of the Seljuk Empire is entirely due to the wise advice, the outstanding guidance, and the governance systematization introduced by Nizam al Mulk, a Persian; of course, all this would prove to be useless without the Seljuk bravery and thunderous attacks. One can call the Seljuk Empire a ‘Turanian’ (or ‘Turkic’ state); but it was equally ‘Iranian’ – notwithstanding the historical forgeries of the Orientalist gangsters of the Anglo-American universities.

Nizam al Mulk is perhaps the person, who studied best the infinite intrigues that occurred on daily basis among all the rulers who enjoyed some portion of power due to the already discussed phenomenon of the Abbasid Caliphate’s fragmentation. Highly respected and incessantly consulted by Tughril, Chaghri and their children, Nizam al Mulk methodically guided them in the splendid attempt to terminate the Abbasid Caliphate’s fragmentation. First, they consolidated their control across the northern part of the Iranian plateau until 1046-7. In 1048, they attacked an Eastern Roman – Georgian army near today’s Pasinler (or Hasankale), east of Erzurum, in the less publicized but historic battle of Kapetron. After ensuring a great capital for themselves at Isfahan (1050), in the Iranian plateau’s southern part, Tughril invaded Baghdad (1055), terminated the Buyid dynasty, and (according to modern Turkish Islamist bibliography) ‘liberated’ the Abbasid Caliph; this is however not accurate because it was not possible anymore to restore the original power of the Abbasid Caliphate. The Abbasids remained a weak and impotent dynasty for another 200 years.

Nizam al Mulk set up a series of academies named after him, ‘Nizamiyah’; his major opus Siyasatnameh (‘the Book of the Governance’) was the basic manual that was taught, discussed, and in-depth understood there, after the completion of an entire basic circle of studies. The numerous Nizamiyah academies that the indefatigable Nizam al Mulk founded in various parts of the expanding Seljuk territory were not similar either to the earlier appeared jurisprudential madhhabs or to the regular madrasas (theological schools).

The graduates of every Nizamiyah acquired first a spherical, encyclopedic knowledge, and at a second stage, an excellent command of the diverse methods of a successful administration of the state (one could vaguely compare them to various modern ‘national schools of administration’). Nizamiyah graduates could man the Seljuk administration and deliver spectacular results, due to the innovative and resourceful mindset that they were taught to build and thanks to their persistence on avoiding bureaucracy. Despite his indisputable imperial and administrative genius, Nizam al Mulk was also a combatant, and – contrarily to the worthless and corrupt, modern bureaucrats – he often accompanied his shahs in their campaigns.

Nizam al Mulk was ostensibly against the group of Isma’ilis and their system of secretive and elitist governance. In his book, he expanded on them; this however does not make of him a ‘Sunni’, as modern forgers pretend. He and his Seljuk emperors were Muslims, who did not accept either secretive governance or the particularities of various eschatological, messianic groups like the Isma’ilis (today mistakenly named ‘Sevener Shia’) or the apocalyptic adepts of the Ahl al Bayt (today erroneously called ‘Twelver Shia’), who expected the imminent reappearance of the 12th imam. This is an extra proof that throughout History there is no such sectarian division and false identification as “Turkish Sunni” and “Iranian Shia”; this is a colonial lie and a shameful Orientalist forgery.

All the same, because of the colonially imposed (during the 19th and 20th centuries) sectarianism, which prevails among today’s deceived and disoriented Muslims, Nizam al Mulk is totally unknown among African Muslims and Saudi-impacted Muslims in Southeast Asia, because he is idiotically viewed as “Iranian and therefore Shia”. This externally imposed pseudo-historical dogma is enough to reveal the criminal nature of the colonial countries France and England, of their successor state (USA), and of the various associated structures, like Canada and Australia.

The rise of the Seljuk Empire was the result of great bravery, heroic fascination, and superb imperial administration that greatly contributed to arts, letters, sciences and spirituality; but it was practically speaking the affair of one family. Few victories were enough to catapult the Seljuk Turks to world predominance between China and Rome. This was due to their wisdom, universal culture, and ability to compose out of many diverse elements; they therefore became a pole of major attraction. Within the general context of Modern Turkology, most of the researchers are specializing in the Ottoman Empire (eventually because of the abundance of historical sources) and have a certain predilection and admiration for the Ottomans, who also functioned as one family – only to the detriment of the Empire that they acquired and that they inherited. But this scholarly attitude is very subjective, highly sentimental, and therefore wrong.

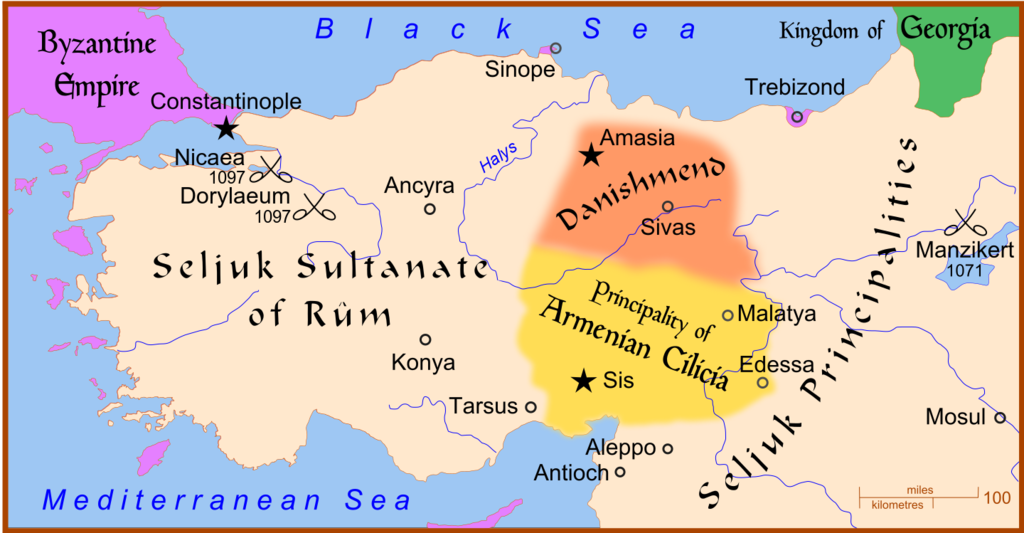

In reality, the Ottomans were superior to the Seljuk Turks only quantitatively. They controlled larger territory and they lasted longer; that’s true. But if one examines the data qualitatively and evaluates comparatively, one easily concludes that the Seljuk were remarkably superior to the Ottomans. However, their undeniably inherent weakness, which consisted in numerous internal conflicts and in incessant, yet unnecessary, family divisions, antagonisms and rivalries, predestined them to fast decay. In fact, the Seljuk Golden Era lasted ca. 100 years: from the dissolution of the Buyid dynasty (1055) to the death of Ahmad Sanjar (1157). After that term, the Seljuk Empire split to several sultanates. The most remarkable among them was certainly the Sultanate of Rum, but that was an Anatolian state, not a major empire across Eurasia. All the same, the History of Mysticism and Spirituality in Seljuk Anatolia eclipsed the Imperial History of that branch of the Seljuk family.

Even Alp Arslan (1063-1072) and Malik-Shah I (1072-1092), who represent the top of Seljuk power, had to engage in battles to eliminate contenders to their throne, and the contenders were none else than their formidable uncles, Kutalmish and Qavurt respectively. Thanks to Nizam al Mulk, Alp Arslan organized a mixed form of feudal empire, at the same time sedentary and nomadic, and for this, he was praised by many Persians like Saadi Shirazi, whereas with the rising sectarianism of the 13th c. he was terribly scolded by Turanians like Shams al-din ibn Kızoğlu (Sıbt İbnu’l-Cevzi). Thanks to Nizam al Mulk’s concepts and Alp Arslan’s rule and practices, a great process of Turanian sedentism across Iran, India, Caucasus, Anatolia and Syro-Mesopotamia was initiated only to strengthen the local populations and transform the Central Asiatic and Siberian nomadism. More importantly, this ingenious idea and brilliant execution introduced -across a vast region- a new social system of mutual social interdependence among sedentary and nomadic populations, thus fortifying the states that would rule these populations. Many populations that still preserve their nomadic nature and traditions across the vast lands from the Mediterranean to the Indus River and from the Persian Gulf to the Tian Shan Mountains and the Siberian permafrost reached the regions where they currently live in the period between the arrival of the Seljuk Turks and the rise of Mughal Empire.

Contrarily to Orientalist deceitful schemes and deliberate misinterpretations, Malik-Shah I did not clash with the dangerous Isma’ili enclave of Hassan al Sabah (1050-1124) in Alamut and in various surrounding locations in the Alborz Mountains because of a hypothetical ‘Sunni’–’Shia’ dispute or an ethnic Persian–Turanian conflict. Simply, as a student of Nizam al-Mulk, he fully accepted and implemented his tutor’s and adviser’s recommendations as regards the nature of the imperial administration and state.

First of all, the small and perfidious Isma’ili state constituted real dynamite in the foundations of the Seljuk Empire; second, the treacherous nature of the Assassins consisted in permanent threat for all the local populations that wanted to live in peace across the Seljuk territory, and not in ceaseless strives. Above all, Malik-Shah I rejected the concept of elitist rule and the existence of spiritual orders with material aspirations. Unfortunately, his successors proved to be quite incompetent and totally unable to face the challenges that they encountered. Because of them and due to their internal discord, the Seljuk Empire was not prepared to oppose the Crusades that started at that moment. For a period of 26 years (1092-1118), four monarchs ruled the vast state that was gradually being decomposed; their incompetence triggered the secession of various lands that formed independent sultanates under the control of various members of Seljuk’s family.

Ahmad Sanjar (1118-1153) was the luckiest of the sons of Malik-Shah I, because he managed to defeat successive invasions from the Kara-Khanids (Afrasiab) of Central Asia, the Ghurids of Khorasan, and the Ghaznavids of the Indus River Valley; however, he faced a crushing defeat at the hands of the Siberian Turanians of Kara Khitan (at the Battle of Qatwan; 1141) and a disastrous uprising among his fellow Seljuk tribesmen (1153). After Ahmad Sanjar’s death, the Turanians of Khwarazm (Chorasmia) conquered the northeastern part of the Seljuk Empire, whereas the vast territory was finally divided among the Seljuk sultans of Hamadan and Baghdad, the Seljuk sultans of Kerman, the Seljuk emirs in Syria, and the Seljuk sultans of Rum (i.e. Romania-Ρωμανία: the Eastern Roman Empire). The endless internal strives of the Seljuk dynasty are no 1 reason of the Crusaders’ success in the Orient. In 1157, Muhammad II ibn Mahmud (1128–1159), Sultan of Seljuk Empire from 1153 to 1159, failed to conquer Baghdad, despite the siege that he laid to the city; this shows that the Great Seljuk state was already weak and that tensions often existed between Baghdad’s impotent caliphs and the various monarchs who ruled in his name.

The Seljuqian-e Rum (1077-1308 / سلجوقیان روم) lasted longer and became the forerunners of the Iranian-Turanian oral culture and the standard bearers of Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh in the most important regions of the Eastern Roman Empire. If you only have a look at the list of the Seljuqian-e Rum monarchs for a moment, you come to realize that their spiritual world and their imperial identity originated from the all-encompassing Turanian-Iranian Universe of Shahnameh: among the 18 sultans, who ruled during a period of 231 years, there were three (3) named Kayqubad, two (2) named Kaykaus, and three (3) named Kaykhusraw. This means that almost half of this dynasty’s rulers named themselves after the most illustrious legendary Iranian kings of the Kayanian dynasty, which represents the focal point of Ferdowsi’s sublime Iranian-Turanian epic poetry.

Throughout Human History, we have known a great number of historical kings, who posthumously entered the world of the legend; but the Seljuqian-e Rum were the only to incarnate the legend and to make out of the realm of the spiritual intuition and the transcendental vision an undeniably historical reality. This fact irrevocably marked the central position that they occupy within the indivisible Iranian-Turanian world. About:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yabghu

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oghuz_Yabgu_State

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oghuz_Turks

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seljuk_(warlord)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seljuq_dynasty

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seljuk_Empire

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tughril

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chaghri_Beg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Kapetron

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Dandanaqan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nizam_al-Mulk

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siyasatnama

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nezamiyeh

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alp_Arslan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malik-Shah_I

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hassan-i_Sabbah

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kerman_Seljuk_Sultanate

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artuqids

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sultanate_of_Rum

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kayanian_dynasty

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khwarazmian_dynasty

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khwarazm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghurid_dynasty

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qara_Khitai

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khitan_people

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_II_ibn_Mahmud

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siege_of_Baghdad_(1157)

The prevalence of the Seljuqian-e Rum in Anatolia transformed this land into the high land of Islamic Civilization, Spirituality and Mysticism. Pretty much like the Islamic world’s gravitational center shifted from Arabia to Mesopotamia with the foundation of Baghdad and the establishment of the Bayt al Hikmah in the middle of 8th c., the Islamic world’s center of imperial power, mysticism and spirituality was relocated from Iran and Caucasus to Anatolia in the late 12th and early 13th c. For many centuries, Anatolia had lost its worldwide radiation; after the end of the Eastern Roman Isaurian dynasty (717-802), the defeat of the Iconoclasts (842), and the downfall of the Paulicians (dispersed in 872 and massively relocated in 970), Anatolia was in ramshackle. The overwhelming rejection of the evil Constantinopolitan theology by the quasi-totality of the Anatolian population irrevocably predestined their future and facilitated the forthcoming Islamization. The spiritual successors to the Iconoclasts and the Paulicians were to be the Mevlevis, the Bektashis, and above all the Qizilbash. The indigenous, traditional Anatolian mysticism predetermined the historical evolution.

The beginning of the Seljuk prevalence in Anatolia is entirely due to Kilij Arslan I (1092-1107; Kılıç Arslan / قِلِج اَرسلان), the first Seljuk to have Konya-Iconium as capital. He managed to defeat three Crusader armies and to secure a sizeable portion of Anatolia for his expanding state. He was a great warrior and an illustrious mystic. However, many scholars want to deliberately forget the fact that the two names of this sultan became the emblem of the Iranian Safavid Empire 400 years later! If this sounds somewhat strange, the English translation of the two names will be enough to clarify the case: “Kılıç Arslan” means “the sword holding lion”. See the emblem:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emblem_of_Iran#Early_Modern_Iran_(16th_to_20th_centuries) The topic’s ramifications can be attested as far as Hungary and the Hunyadi family: http://www.nemzetijelkepek.hu/onkormanyzat-kardos_en.shtml

However, the main part of the preparatory work for the rise of Seljuk Anatolia was done by Rukn al-Din Mesud I (1116-1156; Rükneddin Mesud /ركن الدین مسعود) who was able to defeat two Crusader armies (led by the German Conrad III and the French Louis VII) in 1147 and 1148 and to welcome the adhesion of significant portion of the local Eastern Roman population to Islam. Even illustrious members of the Comneni / Komnenos imperial family, like John Komnenos Tzelepes (grandson of the Eastern Roman Emperor Alexios I Komnenos) who married Rukn al-Din Mesud I’s daughter, became Muslim around the middle of the 12th c.

Rukn al-Din Mesud I’s son and successor, Izz ad-Dīn Qilij Arslān bin Masʿūd (rather known as Kilij Arslan II (1156-1192; Kılıç Arslan / عز الدین قلج ارسلان بن مسعود) represents a very successful consolidation stage of the Seljuqian-e Rum; his critical victory at Myriokephalon (SW Turkey: between Isparta and Konya) in 1176 sealed the end of Eastern Roman presence in Anatolia. Kilij Arslan II, who claimed to be a far relative of Heinrich der Löwe (German prince of the Welf family and Teutonic Knight), expanded at the detriment of the Turkmen Danishmends and the Eastern Roman, but, despite his alliance with Saladin, proved to be unable to possibly stop Frederick Barbarossa’s Third Crusade; however, the numbers speak for themselves: for 76 years, the Seljuqian-e Rum were under only two kings – which is tantamount to great stability.

To the court of the Seljuqian-e Rum started flocking numerous Muslim mystics, spiritual masters, erudite polymaths, theologians, interdisciplinary scholars, great architects and artists, philosophers, leading medical doctors, poets, and other prominent intellectuals of those times. Konya had gradually become a major pole of attraction for the world’s leading wise men. In fact, Seljuk Anatolia eclipsed all other parts of the world in terms of spirituality, mysticism, letters, arts and sciences. This is not strange; despite the great confusion caused by colonial Orientalists and Western Medievalists, who elaborate a distortive and highly politicized representation of this historical period by focusing on the Crusades and the bloodshed caused by Papal Pseudo-Christianity, the 13th c. proved to be above all the peak of the Golden Era of Islamic Civilization.

Those were the times when Nizami Ganjavi (1141-1209; today celebrated as the national poet of Azerbaijan), based in South Caucasus, composed his illustrious epics Khusraw and Shirin (1177-1180), Eskandar-Nameh (: the Book of Alexander the Great; 1196-1202), and his apocalyptic eschatological masterpiece Haft Peykar (: the Seven Beauties; 1197), in which he detailed the troubles of seven major lands of civilization that will rise at the End of Time, when a formidable punishment will be adjusted to the evil perpetrator of crimes against those nations. The sublime epic is monstrously misinterpreted by materialistic Western pseudo-academics as “erotic poetry”, because those corrupt and worthless forgers cannot understand what apocalyptic symbolism is all about. The seven nations / lands of civilization are personified by

– Furak (or Nurak; India),

– Yaghma Naz (China, described as the land under the “Khaqan of the Turks”),

– Naz Pari (Turanian Central Asia, named ‘Khwarazm’/Chorasmia),

– Nasrin Nush (Russia, which is in reality Tatarstan, i.e. the Land of the descendants of the Rouran Touranian Khaganate),

– Azarbin (or Azareyon; Africa – called Maghreb, but viewed generally as the ‘West’)

– Humay (the Eastern Roman Empire’s lands), and

– Diroste (Iran, described as the House of Kay Ka’us, an illustrious Shah of Fardowsi’s heroic Kayanian dynasty whose deeds cover the largest part of Shahnameh).

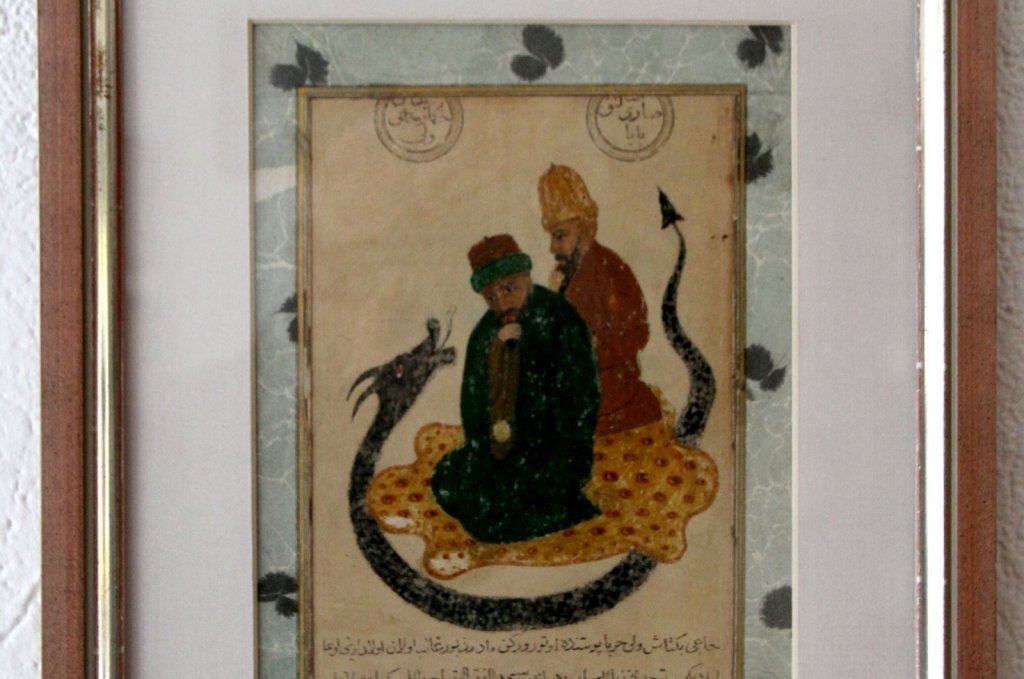

Miniature from a manuscript of Nizami Ganjavi’s Haft Peykar: Bahram Gur in the Turquoise Pavilion with Azarbin, the personnification of Maghreb

Quite indicative of the Rum Sultanate’s court’s proclivity to mysticism, Turanian heroic tradition, and attachment to Ferdowsi’s epic genius is the fact that, only 14 years after Nizami Ganjavi wrote the incomparably revelatory Haft Peykar and only 2 years after he died, the new Seljuk sultan of Rum, Kaykhusraw I’s son, was named Kaykaus I (1211-1220). It was a time of extensive intermarriages with the Eastern Roman imperial family of the Comneni / Komnenoi. Kaykhusraw I (1192-1196 and 1205-1211) was fluent in Roman (‘Medieval Greek’) language and had evidently double Turko-(Eastern) Roman culture.

Kaykaus I’s mother was an Eastern Roman princess, daughter of Manuel Komnenos Maurozomes (Μανουήλ Κομνηνός Μαυροζώμης), who was an Eastern Roman nobleman. Ala ad-Din Kayqubad bin Kaykavus (1220–1237; Alâeddin Keykûbad / علاء الدين كيقباد بن كيكاوس) was the most illustrious sultan of the entire Seljuqian-e Rum dynasty. At the times of his son and successor Kaykhusraw II (1237-1246) starts the fall of the Anatolian Seljuk imperial power, basically due to the religious rebellion of Baba Ishak (1240-1243) and the Mongol victory at the battle of Köse Dağ (1243) where Baiju Noyan (appointed by Ögedei Khan) prevailed. As a matter of fact, this battle is the Seljuk equivalent of the Ottoman defeat in Ankara (1402) by Timur (Tamerlane).

In 1204, one of the most influential dignitaries of the Anatolian Seljuk court invited Muḥyiddin ibn Arabi (1165-1240; full name: Abu Abd Allah Muḥammad ibn Alī ibn Muḥammad ibn Arabī), the Islamic world’s foremost mystic and spiritual master, to Anatolia; Muḥyiddin ibn Arabi’s Futuhat al Makkiyah (: ‘the Mekkan Initiations’) is the greatest text of spiritual revelations (effectuated as result of successive initiations experienced under the guidance of supreme spiritual beings – not after the human fashion) that was ever written in the History of the Mankind. The incredible size (560 chapters or 37 volumes totaling ca. 10000 pages of modern books) of this unique masterpiece of spirituality matters very little when compared to the enthralling contents, which go up to the level of mystical communication with a) the souls of beings that were alive and inhabited the Earth during several generations prior to ours, and b) supreme hierarchies of spiritual beings, intelligences, spirits of elements, and numerous ethereal potentates.

h ttps://ibnarabisociety.org/futuhat-al-makkiyya-printed-editions-claude-addas/

Born in Andalusia’s coastal city of Murcia to parents of Arab and Berber origin, Muḥyiddin ibn Arabi studied in Seville, met and discussed extensively with Ibn Rushd (Averroes), worked as secretary in the city governorate, and undertook incessant travels across North Africa, Syria, Arabia, Mesopotamia and Anatolia. His travels’ most determinant stages took place in Mecca (where he wrote his celebrated masterpiece), in Mosul, in Damascus, and in Eastern Anatolia where he met the students of the great mystic Abdal Qadir Gilani (1078-1166), who was one of the leading mystics of an earlier generation and also the founder of the Qadiriyah mystic order.

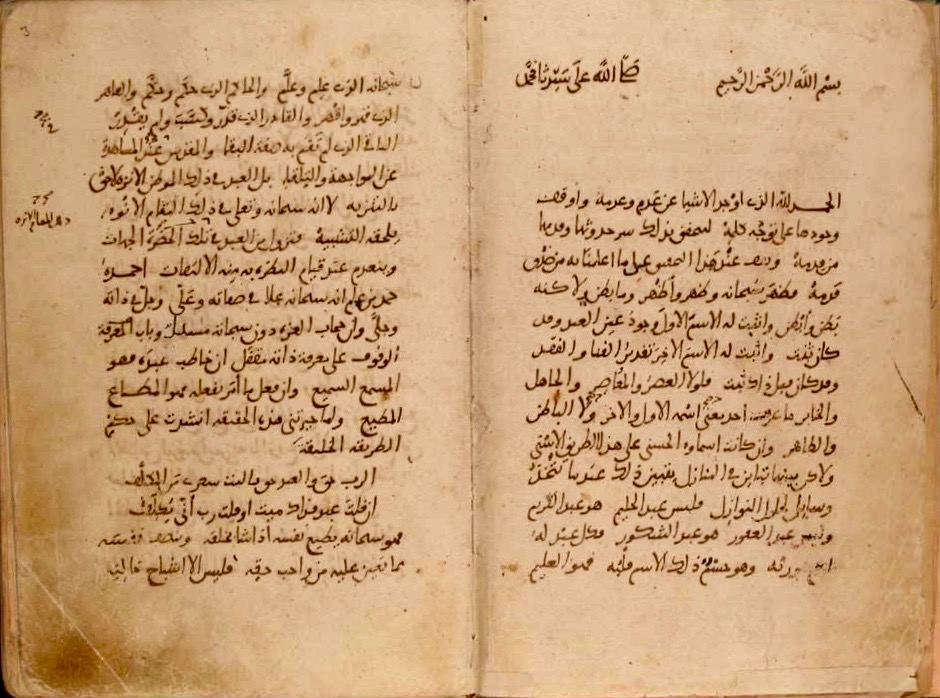

Opening pages Konya manuscript Futuhat, handwritten by Ibn Arabi

It is interesting to notice the details of the theological and jurisprudential affiliation of that great mystic, who was born in Gilan (i.e. Caspian Sea’s southwestern coast) and lived most of his life in Baghdad and in various other locations of Mesopotamia. He was a descendant of Hasan ibn Ali, the second imam and grandson of Prophet Muhammad, but did not belong to Ja’far al-Sadiq’s madhhab; however, if one sees the world through today’s colonially imposed, sectarian and distortive lenses, Abdal Qadir Gilani should have been a Ja’fari. In fact, the great mystic and ascetic was a Hanbali and follower of the jurisprudential school that is nowadays said to be (whereas originally it was not) the most ‘anti-Shia’ or ‘anti- Ja’fari’.

The Qadiriya order had many followers in Anatolia and later in the Balkans, although its diffusion from Mesopotamia to China, to Somalia and to Western Sahara regions was spectacular. The sectarian viewpoint in this regard is posterior and it started with the catastrophic distortion of Ibn Hanbal’s doctrine by the vicious theologian Ahmed ibn Taimiyya whose pseudo-Islamic theology represents a sort of Christianization of Islam. The propagation of his fake Islamic ideas triggered obscurantism, ignorance, and utter hatred for the sciences and the arts among the Muslims; as a consequence, extreme fanaticism prevailed among the gradually decayed, spiritually debased, and increasingly ignorant Muslims of later periods (late 14th – early 16th c.), and then the Safavid reaction (as of 1501) to this situation only added oil to the fire.

Ala ad-Din Kayqubad (Kayqubad I) held in great esteem and sponsored numerous mystics, erudite scholars, poets, architects, artists and spiritual masters. His court was also frequented by very exceptional figures like Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi (1162-1231), a great spiritual master, alchemist, physician and polymath, who explored antiquities at both, the spiritual and the material, levels, thus being an early, Muslim Egyptologist.

Following Kayqubad I’s invitation, the great mystic, theologian and jurisprudential scholar (of the Hanafi madhhab) Baha’ al-Din Muhammad Walad (1151-1231), a Persian originating from Balkh/Bactra (Khorasan), arrived and settled in Konya with his entire family in 1228; this event would have an everlasting impact down to our days. The entire Seljuk royal family was fond of the newly arrived scholar and mystic, who had earlier faced negative treatment from Ala ad-Din Muhammad II of Khwarazm (Chorasmia) in whose state Baha’ al-Din Muhammad Walad used to live. Khwarazm was a Turanian state with constant problems with the Seljuk sultanates, and the main reason Baha’ al-Din Muhammad Walad had problems with his shah was the fact that in Khwarazm’s court the most influential mystic and theologian was Fakhr al-Din al-Razi, the scholar who invented the concept of Multiverse (: the parallel existence of many Universes) and with whom Baha’ al-Din Muhammad Walad had terribly clashed. It was therefore only normal that, to flee the Mongol invasions and to get rid of Ala ad-Din Muhammad II’s enmity and disgrace, Baha’ al-Din Muhammad Walad found a subterfuge in Seljuk Anatolia. The everlasting impact is due to the prodigious poetry composed and the mystical exploits performed by his son, Jalal ad-Din Mohammad Rumi, who is also known as Mawlana or Mevlana.

Jalal ad-Din Rumi (1207-1273; جلالالدین محمد رومی) surpassed by far his father’s fame, literary mastership, mystical experience, intellectual acumen, spiritual ingenuity, and posthumous fame, being one of the Islamic world’s foremost mystics, poets, and holy men. Bringing spiritual activities at the epicenter of material life, Rumi turned dance into active meditation, and thus made of Anatolia the worldwide epicenter of all later Islamic mysticisms. He is considered as the founder of the Mevlevi Spiritual Order (the ‘tariqa’ of the ‘whirling dervishes’), although it is very clear that his son and his disciples founded the Order after Rumi’s death. In younger age, he was fascinated with the literary masterpieces of the mystic Sana’i Ghaznavi (1080-1141); remarkable influence on Jalal ad-Din Rumi was also exerted by his father, by the famous Persian Khorasani mystic and poet Farid ud-Din (1145-1221; known as Attar of Neyshapur), and by Muḥyiddin ibn Arabi. But the close companionship he had with Shams-e Tabrizi (1185-1248), a supreme spiritual hierophant and mystic, was the most determinant factor of his spiritual advance, mystical comprehension, sublime poetry, and whirling dance conceptualization as meditation technique.

Did Jalal ad-Din Rumi actually meet Muḥyiddin ibn Arabi?

This question has been raised by many modern scholars, although on the basis of several historical sources there is clear evidence that they first met during Rumi’s first arrival to Damascus, and later again during Rumi’s formative years there. Furthermore, there is ample evidence that several disciples of ibn Arabi (notably Sadr al-Din al-Qunawi) were companions of Rumi and that Shams-e Tabrizi knew personally ibn Arabi very well. In addition, several literary patterns and terms testify to a spiritual, intellectual and philosophical connection, despite the fact that the essence, the contents, and the forms of both masters of Islamic spirituality and mysticism differed greatly, pretty much like their respective quests, explorations, devotions, spiritual exercises, and transcendental experiences did.

Mausoleum of Jelaleddin Rumi Mevlana, Konya – Turkey

Rumi was a human, who discovered the divine world through love and through strict imitation/repetition of Prophet Muhammad’s manner of life; Muḥyiddin ibn Arabi was a man contacted by spiritual hierarchies, entrusted with the revelation of spiritual occurrences, and endowed with unique qualities to describe in human words unfathomable situations comprehended only through spiritual initiation. An enlightened man like ibn Arabi could never be strictly bound to only one religion.

Closer to Muḥyiddin ibn Arabi was indeed Haji Bektash (1209-1271; Hacı Bektaş-ı Veli / حاجی بکتاش ولی); born in Neyshapur (Khorasan), he was a descendant of Musa Kazim, the 7th imam and son of Ja’far al-Sadiq. He fled westwards because of the Mongol invasions and he arrived in Seljuk Anatolia in the late 1220s or early 1230s. He belonged to the Ja’fari jurisprudential tradition (madhhab), which is quite normal as he retraced his ancestry to the 6th imam’s son. Given his Arab ancestry, it is ridiculous to entertain discussions about his ethnicity (Persian or Turkic) as Western nonsensical Orientalists do; Haji Bektash was certainly acculturated among all Iranians and Turanians between Central Asia and Anatolia. However, this issue can allow us to better assess the locally prevailing ethnic and cultural environment; if a person of Arab descent, like Haji Bektash, living in Khorasan, preferred to bear a Turkish name, i.e. Bektaş, this means that we cannot afford anymore to consider that vast NE Iranian region as exclusively Persian (as fallacious colonial Orientalists do), but as predominantly Turanian. In his young age, Haji Bektash was apparently fascinated with the mystical poetry of the Turanian spiritual master, mystic, and Hanafi theologian Ahmed Yesevî (1093-1166; قوجا احمەت ياساۋٸ), the founder of Yasawiyah (Yeseviye) order.

The oldest painting of the Muslim mystic Haji Bektash Veli

Modern forgers and Western impostors try to associate Haji Bektash with the Qalandariyah Order (which is wrong) and with Baba Eliyas al-Khorasani, another Khorasani mystic who had settled in Anatolia and instigated the Babai revolt that was led by Baba Ishak in 1239. That’s totally false, because Haji Bektash, despite his Batiniyya approach to Islam’s holy scriptures (as per which all holy scriptures have ‘external’ and ‘internal’-mystical meaning), reprimanded the Isma’ili enclave in Iran, denounced Baba Ishak’s plot for the establishment of a Crypto-Christian state in Amasya (Anatolia), and condemned Baba Ishak’s infamous pretensions that he was a ‘prophet’. As a matter of fact, Haji Bektash was greatly esteemed by everyone in the Anatolian Seljuk court where they appreciated his contribution to the combat against the rebellion and to the refutation of anti-Islamic concepts among Turanian nomadic settlers in Anatolia. All the same, the early Bektashi Order accepted in their lodges (khanqah) many earlier adepts and followers of Baba Ishak, who had repented and regretted, and numerous participants in the failed rebellion. The Bektashi Order played later a determinant role in the formation of the Ottoman Sultanate and Caliphate and in the relations between the Ottomans and the Safavids.

The Seljuk Turks managed to assimilate among them a great number of Anatolian, Eastern Roman populations. This topic is critical in understanding later historical developments in the region. Whereas the Achaemenid Iranians failed to plainly assimilate Anatolia during their rule (546-330 BCE) and finally only later (during the Seleucid and Roman times) we clearly attest an undeniable Iranian cultural impact on the various Anatolian kingdoms, the Rum Sultanate proved to be far more efficient in rapidly shaping a diverse yet inclusive Anatolian Muslim identity which revolves around the Iranian-Turanian epic traditions and legends and an Islamic interpretation of the Eastern Roman Christianity. About:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kilij_Arslan_I

https://tr.wikipedia.org/wiki/I._

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mesud_I

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Tzelepes_Komnenos

https://tr.wikipedia.org/wiki/II._K%C4%B1l%C4%B1%C3%A7_Arslan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kilij_Arslan_II

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Myriokephalon

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaykhusraw_I

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaykaus_I

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kayqubad_I

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaykhusraw_II

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_K%C3%B6se_Da%C4%9F

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nizami_Ganjavi

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Babai_revolt

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ibn_Arabi

h ttps://ibnarabisociety.org/influence-of-ibn-arabi-on-the-ottoman-era-mustafa-tahrali/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abdul_Qadir_Gilani

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qadiriyya

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abd_al-Latif_al-Baghdadi

https://iranicaonline.org/articles/baha-al-din-mohammad-walad-b

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rumi

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khwarazmian_dynasty

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_II_of_Khwarazm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fakhr_al-Din_al-Razi

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attar_of_Nishapur

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mevlevi_Order

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sufi_whirling

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shams_Tabrizi

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haji_Bektash_Veli

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bektashi_Order

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ahmad_Yasawi

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baba_Ishak

—————————————————-

Download the chapter in PDF: