Pre-publication of chapter X of my forthcoming book “Turkey is Iran and Iran is Turkey – 2500 Years of indivisible Turanian–Iranian Civilization distorted and estranged by Anglo-French Orientalists”; chapters VI, VII, VIII, IX and X form Part Three (Turkey and Iran beyond Politics and Geopolitics: Rejection of the Orientalist, Turcologist and Iranologist Fallacies about Achaemenid History) of the book, which is made of 12 parts and 33 chapters.

Until now, 14 chapters have been uploaded as partly pre-publication of the book; the present chapter is therefore the 15th (out of 33). At the end of the present pre-publication, the entire Table of Contents is made available. Pre-published chapters are marked in blue color, and the present chapter is highlighted in gray color.

In addition, a list of all the already pre-published chapters (with the related links) is made available at the very end, after the Table of Contents.

The book is written for the general readership with the intention to briefly highlight numerous distortions made by the racist, colonial academics of Western Europe and North America only with the help of absurd conceptualization and preposterous contextualization.

———————————————————

Ahura Mazda, as preached by Zoroaster and as worshipped by the monotheistic Achaemenid dynasty, was heavily impacted by Assur (Ashur), the Sargonid Empire of Assyria, and the Assyrian monotheism, which is at the origin of every Biblical and Islamic concept of monotheism.

History of Religions is a field that was never duly explored by Western Iranologists in their effort to write the History of Ancient Iran and to represent spirituality, cult, mysticism, imperial epiphany, morality and transcendental faith in Pre-Islamic Iran. And for a very good reason! As it had happened in Ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, Anatolia and Canaan for millennia before the rise of the Achaemenid dynasty, Iran was also the terrain in which numerous religious conflicts took place.

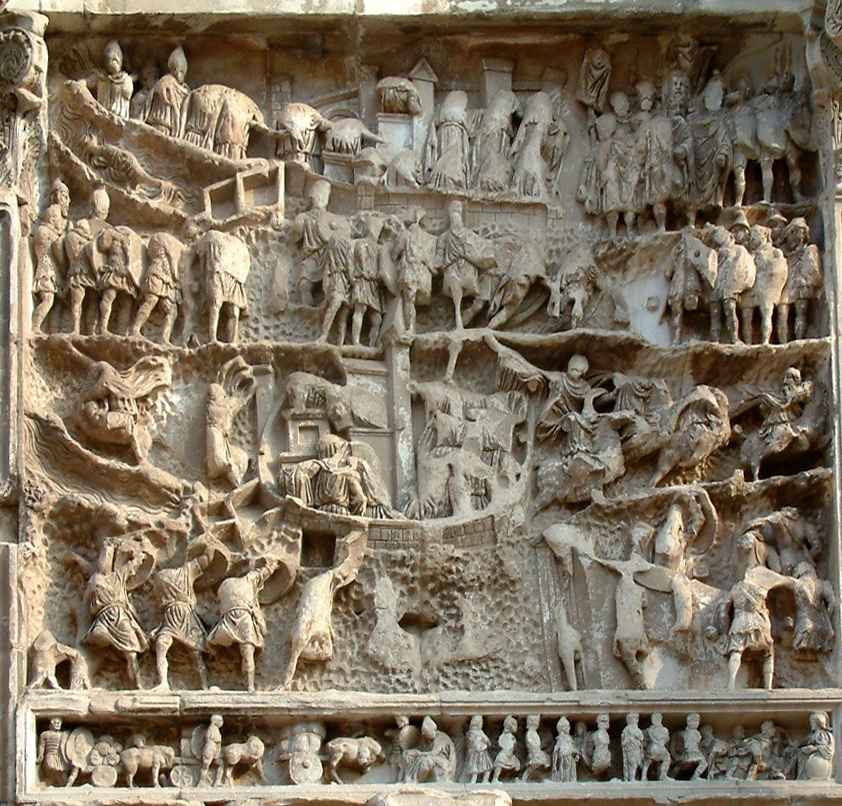

These spiritual and material clashes lasted long and were at times far more ferocious than a) the Catholic Frankish Crusades undertaken by the Western European rulers, b) the 4th–5th c. Christian massacres of hundreds of thousands of followers of the Ancient Egyptian, Berber, Roman, Greek and other religions, and c) the 4th–17th c. Christian killings of thousands of adepts of any theological-Christological system that happened to be considered as ‘heretical’ by the Roman Church, i.e. the Arians, the Monophysites (Miaphysites), the Nestorians, the Iconoclasts, the Paulicians, the Bogomiles, the Knights Templar, etc.

Although Western Iranologists several times managed to successfully identify the existence of opposite beliefs, concepts, cults and faiths in texts and monuments, they basically ended up with a very confusing and misleading representation of the History of Ancient Iranian religions. More specifically, they failed to systematize the presentation of all these opposite beliefs, faiths and religious systems, which were developed in Ancient Iran, and to denote them by means of independent specific names, which could eventually be merely conventional.

Yet, the existing historical sources reveal to us that without a systematized historical-religious study of the material record, the History of the Achaemenids, the Arsacids and the Sassanids will definitely remain largely incomprehensible. However, fully plunged into their catastrophic materialism, ideological militantism, and obdurate sectarianism, the racist academics of the Anglo-Saxon colonial countries have shown only little interest to accurately assess numerous historical facts on the basis of the existing textual/epigraphic evidence and to identify their reason as due to spiritual polarization, moral conflict, and religious clash.

They insidiously distorted the History of Ancient Iran by attributing socioeconomic causes and imperial motives to all the historical facts and developments that took place, thus projecting their wretched mindsets and perverse opinions onto the historical past that they purportedly wanted to ‘interpret’.

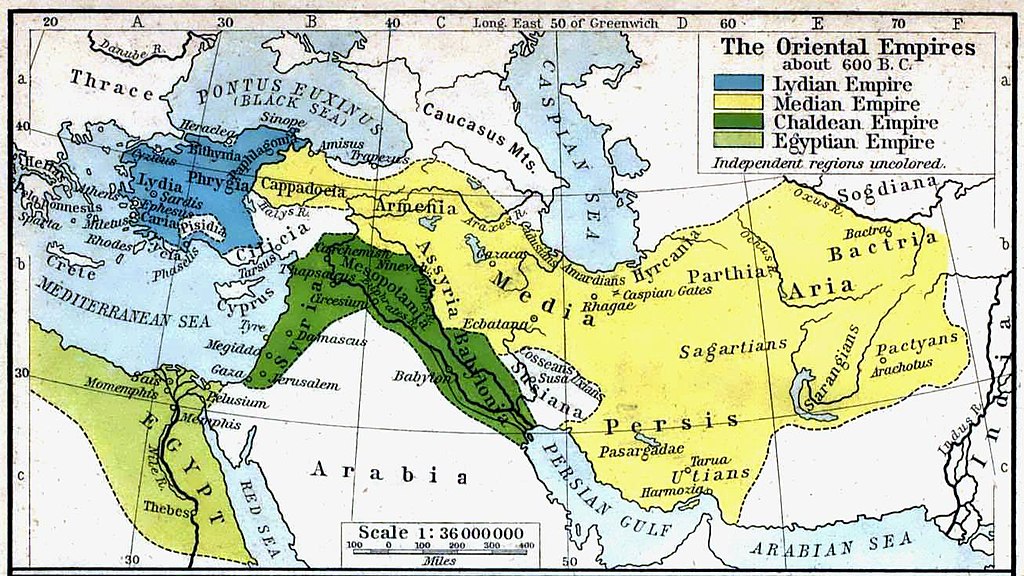

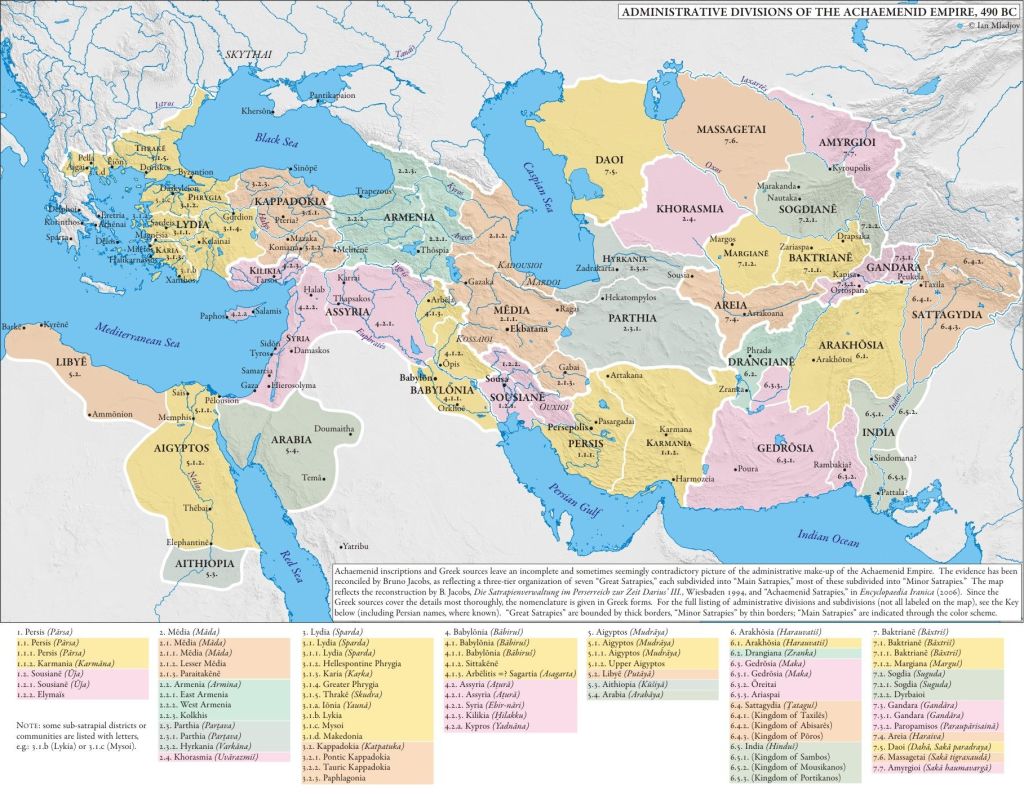

In this regard, we can find a very good example in the well-known case of turmoil that took place at the end of the reign of Kabujiya / Cambyses: the end of the great emperor, who invaded Egypt, Libya and the Sudan (i.e. Cush / Ancient Ethiopia), the pernicious attempt of the Magi to obtain imperial and spiritual power by helping the preposterous impostor Gaumata to usurp the throne, the ensuing chaotic situation, and the final prevalence of Darius I the Great testify to a formidable religious clash between two diametrically opposed and antagonistic priesthoods.

Behistun Inscription and relief, near Hamadan (Ecbatana, NW Iran): Darius I the Great steps on the body of the impostor Gaumata; the conspiracy against the Achaemenid court and the ensuing clash were entirely spiritual and religious of character. The Mithraic Magi never accepted the monotheistic preaching of Zoroaster which was sacrosanct for the Achaemenid court. That’s why in later periods the Mithraic Magi traveled to Rome and imposed their evil polytheism there.

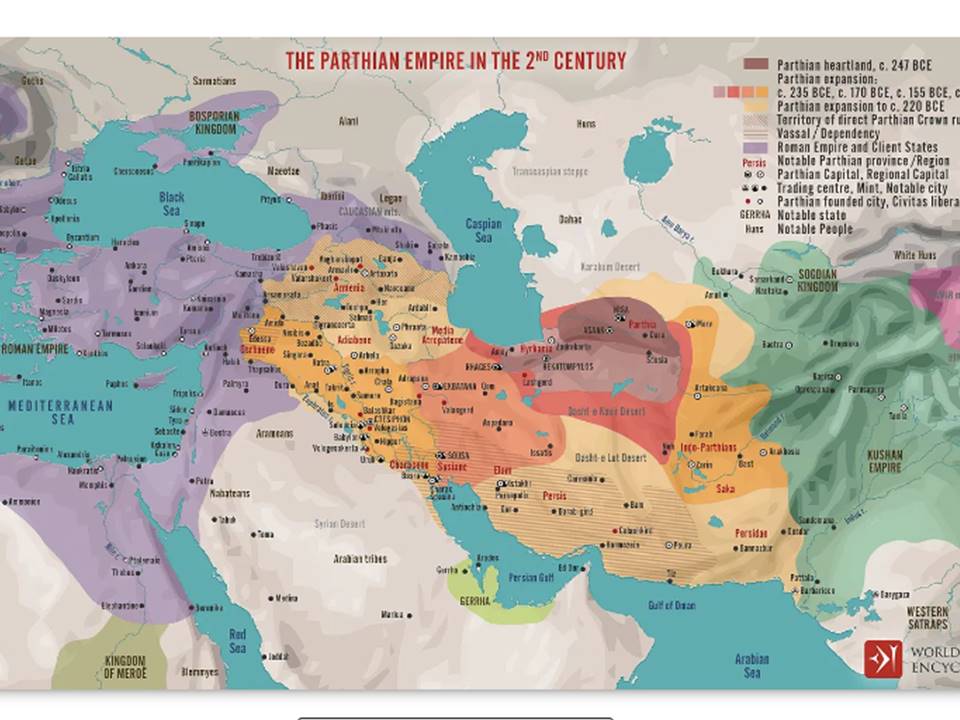

This terrible confrontation reveals an enormous opposition between the irrevocably monotheistic Zoroastrian Achaemenid dynasty, imperial court, administration and the Zoroastrian priests (from one side) and (from the other side) the polytheistic Mithraic Magi, who repeatedly attempted to subvert Iran, control the imperial court, and then corrupt Zoroastrianism. The earliest cosmological myths and mysteries of Mithra (or Mehr), which seem to originate from the wider Khorasan region (today’s Northeastern Iran, Southeastern Uzbekistan, Northwestern Afghanistan, and Tajikistan), recount his exploit to slay the ‘celestial bovines’; much later, following the diffusion of Mithraism across Central and Western Europe, this trait gave birth to the evil religious, spiritual, and cosmological concept of tauroctony.

For the Achaemenid court and the vicars of Zoroastrian monotheism, Mithraism was an abomination. Different mythologization of the same divinity denotes always the existence of very divergent priesthoods, and it therefore testifies to a very dissimilar religion. One should never confuse between a) Mithra (Mehr) as a Zoroastrian divinity subordinated to Ahura Mazda and b) Mithra as the central divinity of Mithraism to which a totally contrasting array of counterfeit mythical themes were ascribed. About:

http://www.tertullian.org/rpearse/mithras/display.php?page=tauroctony

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tauroctony

Parthian relief from Zahhak Castle in East Azerbaijan province, Iran: a bird (possibly eagle) stands on the back of a ball. This may be the very original mythical narrative and form of Mithraic tauroctony.

A negative consequence of Cyrus the Great’s conquest of Babylonia is the fact that the contact with the millennia-long, spiritually powerful, polytheistic Babylonian priesthood of Marduk strengthened the Mithraic Magi enormously and enriched the Mithraic theology considerably. It was then that numerous polytheistic Babylonian concepts, traits, elements, themes and trends were transferred into the early Iranian Mithraism, notably the motif of the dying and resurrected Tammuz, the concept of ‘ab ovo’ Creation, the narrative of the powerful hero and hunter (with the traits of Gilgamesh / Nimrud being passed onto the Iranian Verethragna), and the theme of the mystical banquet. About:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dumuzid

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_egg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indo-European_cosmogony

https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/cosmogony-i

https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/cosmogony-ii

https://iranicaonline.org/articles/bahram-1

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Verethragna

Click to access Henkelman-Gilgamesh.pdf

https://www.livius.org/articles/misc/great-flood/flood3_t-gilgamesh/

https://www.ancient.eu/gilgamesh/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epic_of_Gilgamesh

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gilgamesh

Above: Terracotta plaque of the Amorite Period (2000-1600 BCE) of Babylonia, depicting the earliest representation of Tammuz (Dumuzid in Sumerian) dead in his coffin, before his resurrection; below: Marduk depicted on a Kudurru stele of the Kassite Babylonian king Meli-Shipak II (1186-1172 BCE), one of the last kings of the Kassite dynasty.

Zoroastrianism stands in firm opposition to the ‘ab ovo creation’ concept (which is the earliest form of the evil and pathetic ‘Big Bang’ theory):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_egg#Zoroastrianism_mythology

The strong Zoroastrian faith of the Achaemenid rulers, their steadfastness, and their prevalence throughout the empire (xšāça) prevented the evil Magi from controlling spiritually and fanaticizing the masses with the aforementioned mythological topics in the central Iranian provinces, namely the Iranian plateau. However, Mithra and his evil Magi traveled southeastwards to the Indus Delta region and westwards to Anatolia, Caucasus and Scythia (Russia–Ukraine).

Actually, what had happened with the Iranian conquest of Babylonia was that the millennia-long Assyrian monotheistic–Babylonian polytheistic controversy, which had caused a myriad of wars in Mesopotamia and throughout the Orient before the rise of Cyrus the Great, found other means of expression, being reproduced among other nations. In fact, the Mesopotamian spiritual-religious confrontation was simply transplanted within Achaemenid Iran. It was not a matter of mere coincidence that the Achaemenids appeared as the spiritual, intellectual and cultural offspring of Sargonid Nineveh; it was a normal consequence of the fact that Zoroaster had lived in monotheistic Nineveh, was educated there, was initiated into the Assyrian imperial universalism, and later tried to transfer the doctrine among Iranians.

The first film (movie) in the History of Mankind; the monotheistic Assyrian Emperor Tukulti Ninurta I (1244-1207 BCE) is portrayed twice, standing and then kneeling, in front of the aniconic representation of God as baetylus (betyl, i.e. a meteorite). From the Temple of Ishtar at Assur (Assyria), Iraq; nowadays in Pergamon Museum, Berlin, Germany

In terms of History of Religion, Cyrus the Great’s conquest of Babylonia (539 BCE) reversed, revenged and canceled the earlier downfall of Assyria and Nineveh (614-612 BCE) to the Babylonian armies of Nabopolassar I. In terms of Imperial History, Cyrus the Great postured as the God-blessed savior and the genuine restorer of the Sumerian – Akkadian – Assyrian-Babylonian universal(ist) monarchy, denouncing (and overthrowing) the Nabonid dynasty of Babylonia (625-539 BCE) in the same manner the Sargonids of Assyria (722-609 BCE) had decried Babylonian polytheism and Elamite insanity for millennia. About:

https://www.livius.org/articles/person/cyrus-the-great/

https://www.livius.org/sources/content/cyrus-cylinder/

https://www.livius.org/sources/content/mesopotamian-chronicles-content/abc-7-nabonidus-chronicle/

https://www.livius.org/pictures/a/tablets/abc-07-nabonidus-chronicle-obverse/

http://www.etana.org/node/6612

https://www.ancient.eu/Cyrus_the_Great/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fall_of_Babylon

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyrus_Cylinder

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nabonidus_Chronicle

Assur in symbolic representation

Epiphany of the only God Ashur (Assur) above the Tree of Life, next to it the Assyrian emperor Ashurnasirpal II (883-858 BCE), represented twice, officiates as emperor and as high priest, under the blessing of Assur. From the throne room of Kalhu (modern Nimrud in North Iraq), capital of Ashurnasirpal II

Of course, despite the evident Assyrian spiritual, intellectual, cultural and artistic impact, Zoroastrian monotheism is an original religious phenomenon and all the therein incorporated Assyrian monotheistic concepts were stated in purely Iranian terms and codes, symbols, connotations and forms. But this fact triggers two very simple questions:

– What did the original Iranian religion before Zoroaster look like?

– Was the original Iranian religion before Zoroaster a religious system that looked closer to Zoroaster’s preaching or to an early form of Mithraism?

Due to the lack of textual evidence antedating the establishment of the Iranian monarchy by Cyrus the Great, it is difficult to respond straightforwardly to these questions. Old Achaemenid cuneiform seems to have been invented by Assyrian imperial scribes only few decades prior to the establishment of the Iranian monarchy; the Iranian imperial scribes were indeed well-educated in Sargonid Nineveh at the time of Assurbanipal (669-625 BCE); that’s why they were also perfectly acquainted with, and very well versed into, Assyrian-Babylonian, Elamite, and (to some extent) Sumerian languages and cuneiform writings (Sumerian was already a dead language for 1500 years before the early Achaemenids; so to them it was like Latin to Western Europeans today).

Assur in Assyria (above) & Ahura Mazda in Iran (below)

Ashurnasirpal II is hunting under the auspices of Ashur

Darius defeated his enemies under the auspices of Ahura Mazda

However, we have several indications that, among the Iranian-Turanian nations, there was a long past of grave religious conflicts that ended with the prevalence of Zoroastrianism under Cyrus the Great.

First, all posterior sources narrate the ‘mythical’ and ‘heroic’ stages of Iranian Pre-history and Proto-history as reflecting a dual environment of permanent conflict between the Good and the Evil. Negative thought, word, action or deed among humans is indeed of spiritual origin and impact (Ahriman).

Second, the basics of Zoroastrian cosmogony and cosmology, the context of Zoroastrian moral world vision, and the quintessence of Zoroastrian soteriology show a certain number of potential parallels with Tengrism, i.e. the earlier form of Turanian religion. And this is exactly what has been missing until now in every historical-religious research about the Achaemenid Empire: the strong link between the pre-Zoroastrian Iranian–Turanian religious monotheistic system and Tengrism. There are many linguistic affinities in this regard; furthermore, basic Zoroastrian religious terms reflect pre-Zoroastrian monotheistic fundamentals that had evidently Turkic origin. The topic is very vast, but at this point, I will try to place it in a brief diagram:

Zoroastrianism is the religion based on Zoroaster’s preaching, which consists in the systematization of earlier Turanian Tengrism, after a deep spiritual study of Assyrian monotheism, cosmogony, cosmology, mythical worldview, imperial universalism, eschatology and soteriology; it seems that what Zoroaster, the Turanian prophet from Atropatene / Azerbaijan truly did was to contextualize elements of the early Tengrism and Tengri-related concepts within the Mesopotamian spiritual-cultural order, while preserving the Turanian–Iranian terms; he therefore created a new dogma and doctrine.

Supreme symbols of Tengrism: the sacred circle in the interior of the Mongolian yurt

Since the Mithraic Magi of the Achaemenid times were so evidently subversive against the universal empire of Cyrus the Great and Cambyses, we can deduce that the early Iranian Magi, who opposed Zoroaster and his system, defended an earlier, polytheistic system of faith that was in straight clash with the pre-Zoroastrian form of Tengrism, which was the original faith of the Turanians and the Iranians before the establishment of the Achaemenid dynasty. A series of systematic linguistic studies and historical-religious researches about the said topics would lead to impressive results. About:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tengri

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashavan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asha

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ashina_tribe

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amesha_Spenta

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/G%C3%B6kt%C3%BCrks

https://www.discovermongolia.mn/blogs/the-ancient-religion-of-tengriism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zoroastrianism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tengrism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mithraism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mithra

————————————————–

FORTHCOMING

Turkey is Iran and Iran is Turkey

2500 Years of indivisible Turanian – Iranian Civilization distorted and estranged by Anglo-French Orientalists

By Prof. Muhammet Şemsettin Gözübüyükoğlu

(Muhammad Shamsaddin Megalommatis)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE

CONTENTS

PART ONE. INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER I: A World held Captive by the Colonial Gangsters: France, England, the US, and the Delusional History Taught in their Deceitful Universities

A. Examples of fake national names

a) Mongolia (or Mughal) and Deccan – Not India!

b) Tataria – Not Russia!

c) Romania (with the accent on the penultimate syllable) – Not Greece!

d) Kemet or Masr – Not Egypt!

e) Khazaria – not Israel!

f) Abyssinia – not Ethiopia!

B. Earlier Exchange of Messages in Turkish

C. The Preamble to My Response

CHAPTER II: Geopolitics does not exist.

CHAPTER III: Politics does not exist.

CHAPTER IV: Turkey and Iran beyond politics and geopolitics: Orientalism, conceptualization, contextualization, concealment

A. Orientalism

B. Conceptualization

C. Contextualization

D. Concealment

PART TWO. EXAMPLE OF ACADEMICALLY CONCEALED, KEY HISTORICAL TEXT

CHAPTER V: Plutarch and the diffusion of Ancient Egyptian and Iranian Religions and Cultures in Ancient Greece

PART THREE. TURKEY AND IRAN BEYOND POLITICS AND GEOPOLITICS: REJECTION OF THE ORIENTALIST, TURKOLOGIST AND IRANOLOGIST FALLACIES ABOUT ACHAEMENID HISTORY

CHAPTER VI: The fallacy that Turkic nations were not present in the wider Mesopotamia – Anatolia region in pre-Islamic times

CHAPTER VII: The fallacious representation of Achaemenid Iran by Western Orientalists

CHAPTER VIII: The premeditated disconnection of Atropatene / Adhurbadagan from the History of Azerbaijan

CHAPTER IX: Iranian and Turanian nations in Achaemenid Iran

CHAPTER X: Iranian and Turanian Religions in Pre-Islamic Iran

PART FOUR. FALLACIES ABOUT THE SO-CALLED HELLENISTIC PERIOD, ALEXANDER THE GREAT, AND THE SELEUCID & THE PARTHIAN ARSACID TIMES

CHAPTER XI: Alexander the Great as Iranian King of Kings, the fallacy of Hellenism, and the nonexistent Hellenistic Period

CHAPTER XII: Parthian Turan: an Anti-Persian dynasty

CHAPTER XIII: Parthian Turan and the Philhellenism of the Arsacids

PART FIVE. FALLACIES ABOUT SASSANID HISTORY, HISTORY OF RELIGIONS, AND THE HISTORY OF MIGRATIONS

CHAPTER XIV: Arsacid & Sassanid Iran, and the wars against the Mithraic – Christian Roman Empire

CHAPTER XV: Sassanid Iran – Turan, Kartir, Roman Empire, Christianity, Mani and Manichaeism

CHAPTER XVI: Iran – Turan, Manichaeism & Islam during the Migration Period and the Early Caliphates

PART SIX. FALLACIES ABOUT THE EARLY EXPANSION OF ISLAM: THE FAKE ARABIZATION OF ISLAM

CHAPTER XVII: Iran – Turan and the Western, Orientalist distortions about the successful, early expansion of Islam during the 7th – 8th c. CE

CHAPTER XVIII: Western Orientalist falsifications of Islamic History: Identification of Islam with only Hejaz at the times of the Prophet

CHAPTER XIX: The fake, Orientalist Arabization of Islam

CHAPTER XX: The systematic dissociation of Islam from the Ancient Oriental History

PART SEVEN. THE FICTIONAL DIVISION OF ISLAM INTO ‘SUNNI’ AND ‘SHIA’

CHAPTER XXI: The fabrication of the fake divide ‘Sunni Islam vs. Shia Islam’

PART EIGHT. THE DISTORTED TERM ‘PERSIANATE’

CHAPTER XXII: The fake Persianization of the Abbasid Caliphate

PART NINE. FALLACIES ABOUT THE GOLDEN ERA OF THE ISLAMIC CIVILIZATION

CHAPTER XXIII: From Ferdowsi to the Seljuk Turks, Nizam al Mulk, Nizami Ganjavi, Jalal ad-Din Rumi and Haji Bektash

PART TEN. FALLACIES ABOUT THE TIMES OF TURANIAN (MONGOLIAN) SUPREMACY IN TERMS OF SCIENCES, ARTS, LETTERS, SPIRITUALITY AND IMPERIAL UNIVERSALISM

CHAPTER XXIV: From Genghis Khan, Nasir al-Din al Tusi and Hulagu to Timur

CHAPTER XXV: Timur (Tamerlane) as a Turanian Muslim descendant of the Great Hero Manuchehr, his exploits and triumphs, and the slow rise of the Turanian Safavid Order

CHAPTER XXVI: the Timurid Era as Peak of the Islamic Civilization, Shah Rukh, and Ulugh Beg, the Astronomer Emperor

PART ELEVEN. HOW AND WHY THE OTTOMANS, THE SAFAVIDS AND THE MUGHALS FAILED

CHAPTER XXVII: Ethnically Turanian Safavids & Culturally Iranian Ottomans: two identical empires that mirrored one another

CHAPTER XXVIII: Spirituality, Religion & Theology: the fallacy of the Safavid conversion of Iran to ‘Shia Islam’

CHAPTER XXIX: Selim I, Ismail I, and Babur

CHAPTER XXX: The Battle of Chaldiran (1514), and how it predestined the Fall of the Islamic World

CHAPTER XXXI: Ottomans, Safavids and Mughals: victims of their sectarianism, tribalism, theology, and wrong evaluation of the colonial West

CHAPTER XXXII: Ottomans, Iranians and Mughals from Nader Shah to Kemal Ataturk

PART TWELVE. CONCLUSION

CHAPTER XXXIII: Turkey and Iran beyond politics and geopolitics: whereto?

————————————————————-

List of the already pre-published chapters of the book

Lines separate chapters that belong to different parts of the book.

CHAPTER XI: Alexander the Great as Iranian King of Kings, the fallacy of Hellenism, and the nonexistent Hellenistic Period

CHAPTER XII: Parthian Turan: an Anti-Persian dynasty

https://www.academia.edu/52541355/Parthian_Turan_an_Anti_Persian_dynasty

CHAPTER XIII: Parthian Turan and the Philhellenism of the Arsacids

https://www.academia.edu/105539884/Parthian_Turan_and_the_Philhellenism_of_the_Arsacids

———————————

CHAPTER XIV: Arsacid & Sassanid Iran, and the wars against the Mithraic – Christian Roman Empire

CHAPTER XV: Sassanid Iran – Turan, Kartir, Roman Empire, Christianity, Mani and Manichaeism

CHAPTER XVI: Iran – Turan, Manichaeism & Islam during the Migration Period and the Early Caliphates

———————————-

CHAPTER XVII: Iran–Turan and the Western, Orientalist distortions about the successful, early expansion of Islam during the 7th-8th c. CE

CHAPTER XX: The systematic dissociation of Islam from the Ancient Oriental History

—————————————

CHAPTER XXI: The fabrication of the fake divide ‘Sunni Islam vs. Shia Islam’

https://www.academia.edu/55139916/The_Fabrication_of_the_Fake_Divide_Sunni_Islam_vs_Shia_Islam_

——————————————

CHAPTER XXII: The fake Persianization of the Abbasid Caliphate

https://www.academia.edu/61193026/The_Fake_Persianization_of_the_Abbasid_Caliphate

——————————————–

CHAPTER XXIII: From Ferdowsi to the Seljuk Turks, Nizam al Mulk, Nizami Ganjavi, Jalal ad-Din Rumi and Haji Bektash

————————————————

CHAPTER XXIV: From Genghis Khan, Nasir al-Din al Tusi and Hulagu to Timur

CHAPTER XXV: Timur (Tamerlane) as a Turanian Muslim descendant of the Great Hero Manuchehr, his exploits and triumphs, and the slow rise of the Turanian Safavid Order

CHAPTER XXVI: The Timurid Era as the Peak of the Islamic Civilization: Shah Rukh, and Ulugh Beg, the Astronomer Emperor

———————————————————————–

Download the chapter (text only) in PDF:

Download the chapter (pictures & legends) in PDF: