Pre-publication of chapter XIII of my forthcoming book “Turkey is Iran and Iran is Turkey – 2500 Years of indivisible Turanian – Iranian Civilization distorted and estranged by Anglo-French Orientalists”; chapters XI, XII, and XIII constitute the Part Four (Fallacies about the so-called Hellenistic Period, Alexander the Great, and the Seleucid & the Parthian Arsacid Times) of the book, which is made of 12 parts and 33 chapters. Chapter XI ‘Alexander the Great as Iranian King of Kings, the fallacy of Hellenism, and the nonexistent Hellenistic Period’ and Chapter XII ‘Parthian Turan: an Anti-Persian dynasty’ have already been uploaded as partly pre-publication of the book; they are currently available online here: https://www.academia.edu/105386978/Alexander_the_Great_as_Iranian_King_of_Kings_the_fallacy_of_Hellenism_and_the_nonexistent_Hellenistic_Period

and

https://www.academia.edu/52541355/Parthian_Turan_an_Anti_Persian_dynasty

The book is written for the general readership with the intention to briefly highlight numerous distortions made by the racist, colonial academics of Western Europe and North America only with the help of absurd conceptualization and preposterous contextualization.

—————————-

The very long shadow of the Turanian Parthian Arsacids who ruled Iran (250 BCE – 224 CE) longer than the Achaemenids (550-330 BCE) and the Sassanids (224-651 CE); this silver gilt dish was found in Padishkhwargar, an Arsacid province that corresponds to Tabaristan (of Islamic times) or to Mazandaran and Gilan (of Modern times), i.e. the long and narrow region between the Alborz Mountains and the southern coast of the Caspian Sea. The dish dates back to the last decades of Sassanid rule or the very early Islamic period; it apparently follows the Sassanid artistic traditions, but the main person next to whom there is a brief Pahlavi inscription makes with his left hand a particular sign of mystical recognition among initiates. This sign reminds the typical hand gesture of Gray Wolves (a fist with the little finger and index finger raised).

Colonial historiographers and Orientalists expand much about the philhellenism of the Parthian monarchs at least for the first 250 years of the dynasty, down to the very beginning of the 1st c. CE; this is a fact. However, few questioned how functional this Parthian philhellenism was and what important purposes it actually served. It is true that after Alexander the Great’s death (323 BCE) a chaotic situation prevailed across Iran and many battles were fought by his Epigones; the Seleucid Empire, which incorporated the central Iranian satrapies, was constituted only 11 years after Alexander’s death (312 BCE).

At that moment and for a longer period afterwards, the worst hit province of the Achaemenid Empire was still Fars (Persia); Alexander the Great’s invasions did not involve any other destruction of Achaemenid city or site comparable to that of Parsa (Persepolis). Reflecting pre-existing rivalries, several populations of other Iranian – Turanian provinces may have enjoyed both, Alexander’s attitude against Fars and the destruction of Persepolis. Furthermore, the inevitable transfer of the imperial capital to Babylon must have pleased them too; it offered them space to gradually control as long as the Persian Iranians were in disarray.

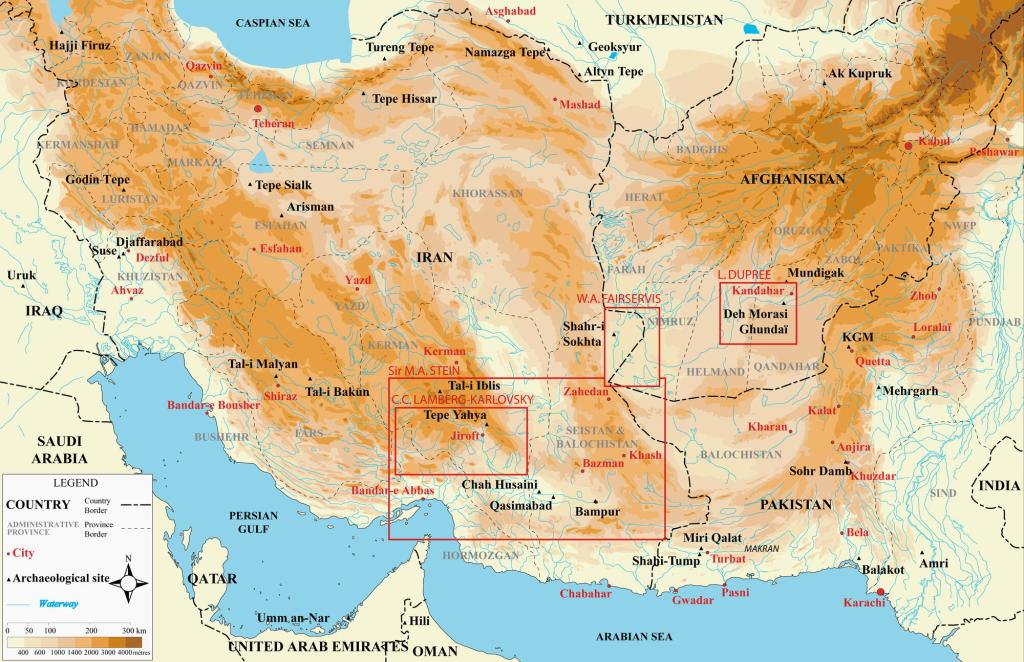

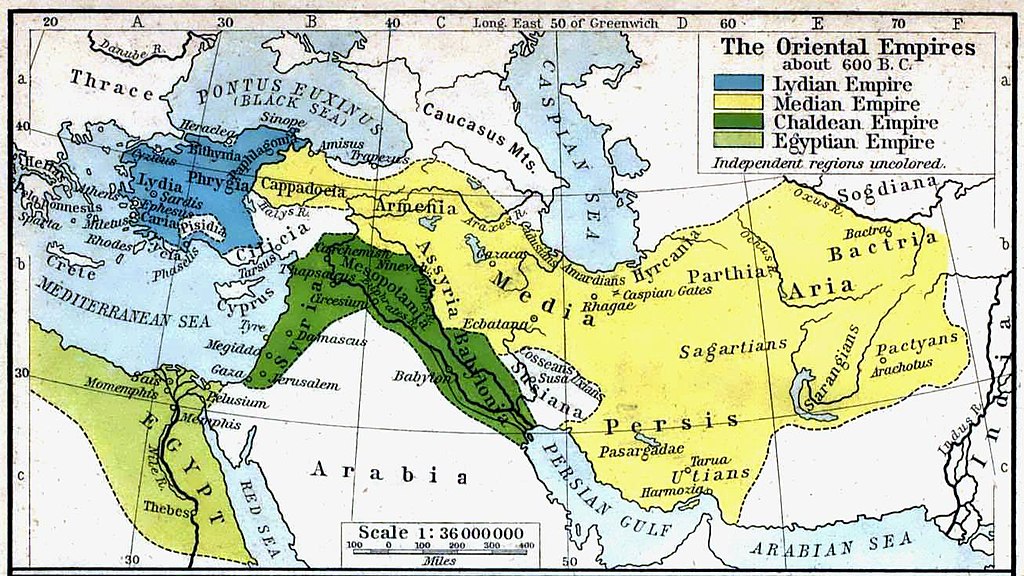

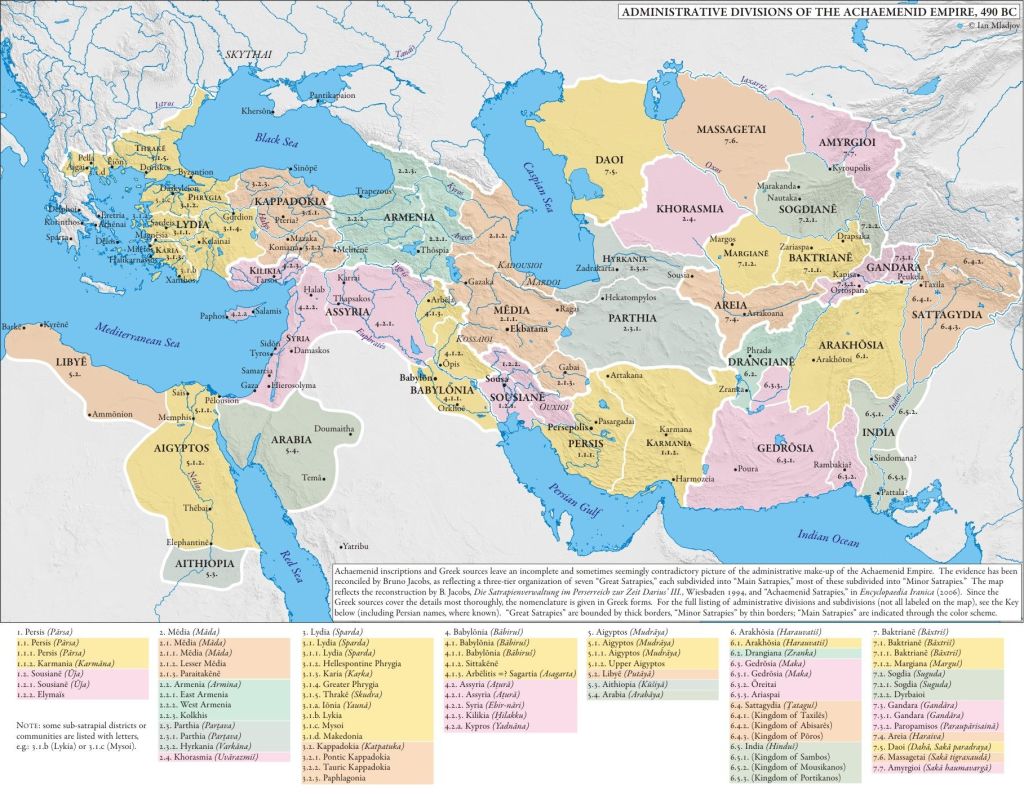

Parthia was already a province of the short-lived Median Empire

Parthia as an Achaemenid Iranian satrapy

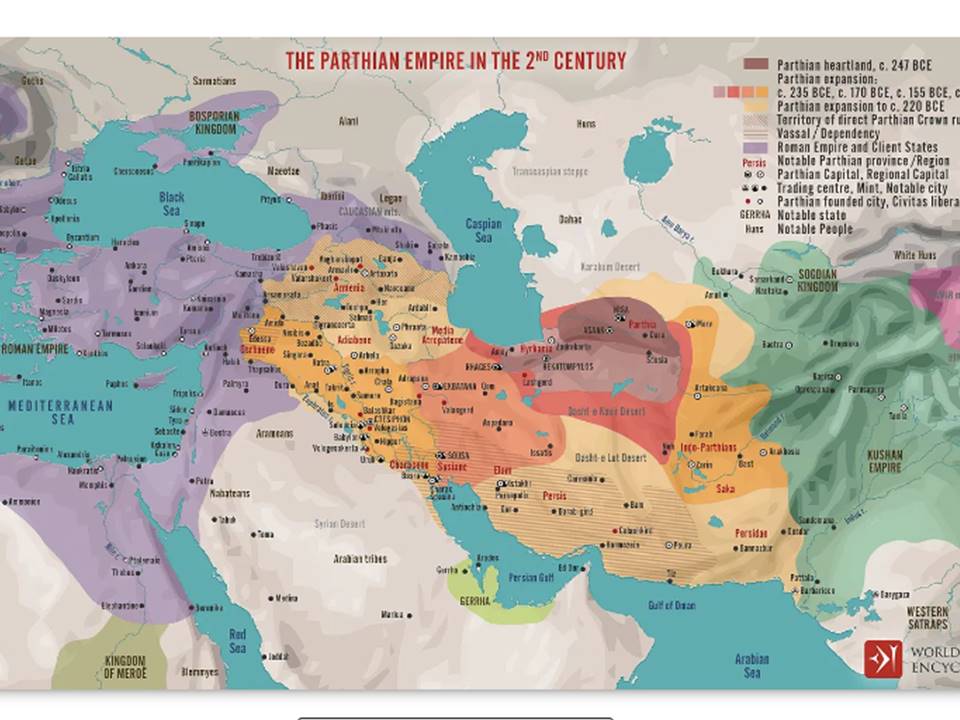

The early period of Arsacid Parthia: 250-200 BCE

The Arsacid Parthian Empire in 94 BCE at its greatest extent, during the reign of Mithridates II (124–91 BCE)

The Arsacid Parthian Empire at the beginning of the first c. CE

Parthia (P-rw-t-i-wꜣ) written in Egyptian hieroglyphic characters: it was one of the 24 subject nations of the Achaemenid Empire (from the Egyptian Statue of Darius I the Great)

Parthian soldier depicted on the façade of Xerxes’ I tomb in Naqsh-e Rustam, ca. 470 BCE

The subsequent transfer of the Seleucid capital to Seleucia in Mesopotamia was a grave mistake of the newly established dynasty, which failed to comprehend the very smart effort of Alexander to favor, befriend and utilize the Babylonians as the principal means to hold his vast empire united. Finally, the Parthians seceded from the Seleucid Empire 60-65 years after its inception. The rise of the Arsacid dynasty meant that, for the first time in History, the central Iranian–Turanian provinces were ruled under a scepter and a throne that were not located in Fars.

It is therefore normal that the Parthians -in their opposition to the Persians (of Fars)- promoted a systematic court philhellenism and contributed to Alexander the Great’s Iranian legitimation and unquestionable incorporation into the imperial identity and history, and to his posterior fame among Iranian–Turanian nations. This stance fully corresponded to their best interests, namely to secure stability across Iran’s central provinces, while facing threats from rivals among the neighboring empires and kingdoms. It is clear that the Turanian attempt was rejected by the Persian Iranians, and of this polarization we attest late echoes that date back to the Islamic times. Accepting Alexander as an Iranian was benediction to the Turanian Parthians and malediction to the Iranian Persians. But the empire (Xšāça) established by Cyrus the Great was indiscriminately Iranian-Turanian.

Despite the Arsacid–Seleucid wars, one must rather conclude that, with their marked philhellenism, the Turanian rulers of Parthia had good relations with the various Greek and Macedonian colonies, which had been established throughout their territory and in several adjacent lands, notably Bactria.

This fact helps also explain why, despite Alexander the Great’s rather negative portrait in Sassanid and Middle Persian sources of the Islamic times’ Parsis, the conqueror of the Achaemenid Empire enjoyed splendid narratives and majestic descriptions by Ferdowsi, Nizami, and many other Islamic Iranian–Turanian poets, mystics, philosophers and historians.

Although followers of Parsism (the form of Zoroastrianism that survived down to our days) in Iran and India have a very negative perception of Alexander the Great, Iranian and Turanian Muslims very much venerate him. About:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parthian_Empire#Hellenism_and_the_Iranian_revival

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_formula_of_Parthian_coinage

One must have no doubt that the term ‘Hellene’ (Greek) is ‘Ionian’ for the Oriental languages. Throughout all the ancient Oriental sources, i.e. Assyrian-Babylonian, Old Achaemenid Iranian, Aramaic, Phoenician and Hebrew, there is not one mention of ‘Greeks’ or ‘Hellenes’; the only term used is ‘Ionian’. This means that in any ancient Oriental language, for the word ‘Philhellene” the corresponding term is “friendly to Ionians”.

It is essential at this point to define the ethnic and cultural links that the Arsacid Parthians felt that they connected them with the ‘Ionians’ with whom they entered in contact. The Parthians accepted the imperial concept because they were integral part of Achaemenid Iran; around 200 years later, the Macedonians, the Ionians and the Aeolians became acquainted with this spiritual notion thanks to Alexander the Great and the practices of Orientalization that he introduced for his soldiers.

However, prior to the acceptance of the imperial ideal, both the Parthians and the ‘Ionians’ had their apparently common concept of governorship that was above the fundamental level of Kurultai, which corresponds to the ‘Ionian’ Amphictyony for settled tribes. This was a military type of rule with man exercising absolute power upon condition of general approval. The traditional Turanian ruler was named in Ancient Ionian (‘Greek’) ‘tyrannos’, and it was pronounced as ‘tu-ran-nos’ with the accent on the first syllable. The term designated the typically Turanian ruler and it serves as an indication of the Turanian origin of the Ionians and the Aeolians. It was actually first used among the Lydians of the Mermnadae dynasty, whose members had apparently names of Turanian origin, notably the founder of the dynasty Gyges whose name was written in Assyrian Annals as Gu(g)gu. About:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kurultai

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amphictyonic_league

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/τύραννος#Etymology

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gyges_of_Lydia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_kings_of_Lydia#Mermnadae

In fact, the Parthian Arsacid philhellenism sheds more light on the inculcation of Turanian populations across Western Anatolia and South Balkans during the first millennium BCE, which is a topic that colonial historians tried systematically to conceal. However, Parthian philhellenism is certainly a form of anti-Persianism, which shows that the Achaemenid times were not a period of peace and concord, as many attempted to depict.

——————— THE GALLERY OF ARSACID RULERS & SOLDIERS —————————

Silver drachma of Arsaces I (247 – 211 BCE) with inscription

Arsaces II (211–191 BCE); coin from the Ray mint

Friyapat/Priapatius (191-176 BCE); coin from the Qumis (Hekatompylos; today’s Saddarvazeh) mint

Coin of Frahat I / Phraates I (176-171 BCE)

Coin of Mehrdat I / Mithridates I (171–138 or 132 BCE), who was the first Arsacid Parthian ruler to be attributed the title ‘King of Kings’, according to Babylonian cuneiform records; the reverse shows Verethragna / Heracles, and the inscription ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΜΕΓΑΛΟΥ ΑΡΣΑΚΟΥ ΦΙΛΕΛΛΗΝΟΣ “Great King Arsaces, friend of Greeks”.

Parthian relief of Mithridates I of Parthia from Xong-e Ashdar (also known as Hung-i Nauruzi), near the city of Izeh, in Khuzestan, Iran; compared to the Achaemenid reliefs, which were the results of an official imperial art, the Parthian reliefs are relevant of provincial artists and craftsmanship; most of the Parthian reliefs are found in the southern range of Zagros Mountains. Parthian reliefs are rather secular and not religious; and not religious; they depict scenes of resting, drinking, and hunting, also including several animal figures.

Mithradat-kert (literally the city of Mithridates I of Parthia) in today’s Nisa (or Nissa or Nusay) in Eastern Turkmenistan; the entrance to the city and the walls, which had to be covered up to prevent further damage from erosion

Mithradat-kert (Ancient Greek: Νῖσος, Νίσα, Νίσαιον; Turkmen: Nusaý or Parthaunisa)

Mithradat-kert

Mithradat-kert

Frahat II / Phraates II (132–127 BCE); coin from the Seleucia mint (in Mesopotamia)

Ardawan I / Artabanus I (127–124 BCE); coin from the Seleucia mint

Coin of Ardawan II / Artabanus II (126–122 BCE)

Coin (drachma) of Mihrdāt II / Mithridates II of Parthia (124–91 BCE); the clothing is Parthian, while the style is Seleucid (sitting on an omphalos). The Greek inscription reads “King Arsaces, the Philhellene”.

Godarz I / Gotarzes I (95-90 BCE); coin from the Ecbatana mint

Coin of Mihrdat III / Mithridates III (87-80 BCE) from the Ray mint

Tetradrachm of the Parthian monarch Urud I / Orodes I (90-80 BCE) from the Seleucia mint

Coin of Sanatruq I / Sinatruces I (77-70 BCE) from the Ray mint

Frahat III / Phraates III (70–57 BCE); coin from the Ecbatana mint

Coin of Mihrdat IV / Mithridates IV (57-54 BCE)

Coin of Urud II / Orodes II (57-38 BCE) from the Mithradat-kert (Nisa) mint

Frahat IV / Phraates IV (38-2 BCE); coin from the Mithradat-kert mint

During the reign of Frahat IV / Phraates IV, there seems to have been a pacification agreement between Parthia and Rome (after the proclamation of Octavian as Emperor in early 27 BCE). According to Roman sources, the Parthians returned to Romans the standards lost in the Battle of Carrhae (53 BCE); this fact was commemorated and presented by Octavian as a victory: this coin (denarius) was struck in 19 BCE. It depicts the Roman goddess Feronia on the obverse, and on the reverse a Parthian soldier who kneels in submission while returning the Roman military standards. It is apparently a matter of utmost symbolism and not the representation of a historical event.

The decentralized administrative and royal power of the Arsacid Parthians allowed for many small, peripheral and vassals kingdoms to surface (Characene, Adiabene, Osrhoene, etc.); there are many possible interpretations of the phenomenon, which was erroneously viewed as result of military weakness in the past. Elymais (in today’s Khuzestan, SW Iran) was one of those vassal states. Coin of Kamnaskires III, king of Elymais, and his wife Queen Anzaze, 1st century BCE

Coin of Tiridat II / Tiridates II (29-27 BCE)

Coin of Frahat V / Phraates V (2 BCE-4 CE)

Vonun I / Vonones I (8-12 CE); coin from the Seleucia mint

Coin of Ardawan II / Artabanus II (10-38 CE) from the Seleucia mint

Vardan I / Vardanes I (40-47 CE); coin from the Seleucia mint

Tetradrachm of Godarz II / Gotarzes II (40-51 CE) minted in 49 CE

Tetradrachm of the Parthian king Vologases I (50-79 CE), struck at Seleucia; on the obverse, there is a portrait of the king who appears to wear a trouser-suit, bear a diadem, and have beard. The reverse depicts an investiture scene, where the king receives the scepter and the divine authority by Ahura Mazda.

The so-called Indo-Parthian Kingdom (19-226 CE) was another small, vassal and peripheral kingdom that was located east of the Parthian Arsacid Empire; it was founded by king Gondophares (Γονδοφαρης/Υνδοφερρης; 19-46 CE) whose name (Windafarm in Parthian and Gundapar in Middle Persian) means ‘May he find glory’ (Vindafarna in Old Achaemenid Iranian). Gondophares originated from the illustrious House of Suren, one of the most prestigious families in Arsacid Iran. He built his own royal city Gundopharron and this name was gradually altered to Kandahar (which is located in today’s Afghanistan). Gondophares’ coin was found in India and bears witness to a clearly Parthian style.

Roman sestertius issued by the Roman Senate in 116 CE to commemorate Trajan’s Parthian campaign

Drawing representing a Parthian archer as depicted on Trajan’s Column in Rome (113 CE)

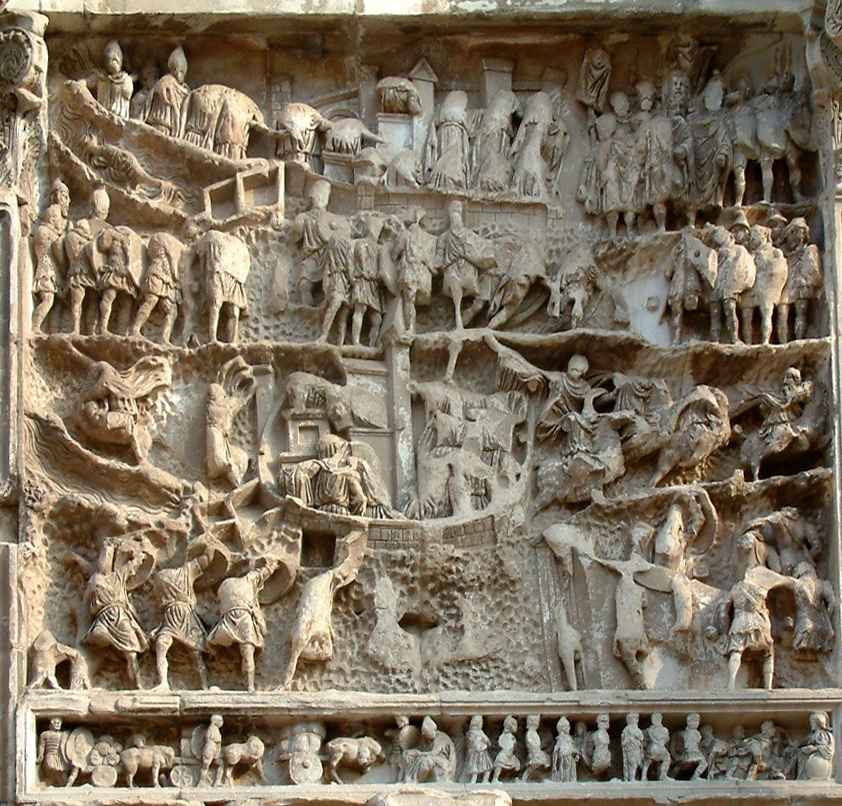

Relief of the Roman-Parthian wars at the Arch of Septimius Severus in Rome (203 CE)

Parthian (right) wearing a Phrygian cap, depicted as a prisoner of war, in chains, held by a Roman (left); Arch of Septimius Severus, Rome, 203 CE

Parthian king making an offering to god Verethragna; from Masjed Soleyman, SW Iran. 2nd–3rd century CE (today in the Louvre Museum)

Silver drachma of the Parthian king Walagash VI / Vologases VI (208-228 CE), penultimate ruler of the Arsacid dynasty. Obverse: King wearing a tiara decorated with deers and ribboned diadem. Reverse: Arsakes I, founder or the Arsacid Parthian dynasty, seating on a throne and holding a bow. From the Ecbatana mint (today’s Hamadan).

Parthian horseman, currently at the Palazzo Madama, Turin

Parthian cataphract fighting a lion, currently at the British Museum

Stucco relief of an infantry soldier, dating back to the Arsacid times (250 BCE – 224 CE); from the Zahhak castle, in Hashtrud, Eastern Azerbaijan, Iran; currently in the Azerbaijan Museum, Tabriz (Iran)

————————————————————————–

Another fact that Western Orientalists tried always to obscure is that the religion of the Arsacids was somewhat divergent from that of the Achaemenids. I don’t mean that the Parthians had a diametrically different or a counterfeit religion; not at all! Simply, in terms of Zoroastrian cosmogony, cosmology, universalism, imperial doctrine, and apocalyptic eschatology, the Arsacids sensibly differed from the Achaemenid Zoroastrian orthodoxy. We have to also bear in mind at this point that the scarcity of the historical sources still prevents us from properly assessing the true dimensions of the religious differentiation.

However, the marked differentiation of the Arsacid monarch from his Achaemenid predecessors suggests another type of royalty, sacrality, spirituality, and morality. As an example for the average readership, I point out here that there has not been even one Old Achaemenid or Imperial Aramaic text -saved down to our days-, which explicitly mentions Zoroaster by name. All the earliest mentions of the name of the founder of the Achaemenid imperial religion are in Middle Persian and in Avestan writings – except for external but largely untrustworthy sources (Ancient Greek and Latin).

All the same, the religious differentiation between the Achaemenid and the Arsacid times did not bring about a drastic religious change, but rather another perception of the divine world; the Parthians continued worshipping Ahura Mazda and keeping themselves far from Ahriman’s attraction. But it appears that, during the Arsacid times, Zoroaster’s preaching was rather perceived as a sacred moral world order; subsequently, the metaphysical terms of the then orally preserved Avesta took a moral dimension and connotation. The spiritual interest seems to have shifted from an imperial order of worldwide salvation to a personal order of moral integrity.

Consequently, examining the nature of this historical-religious change, we may be able to discern that the Achaemenid Zoroastrian orthodoxy, once deprived of its overwhelmingly imperial character, looks rather associated to the moral concepts and the spiritual tenets of Tengrism. For this reason, it is proper not to use the term ‘Zoroastrianism’ for all the historical periods after the fall of the Achaemenid Empire, because religiosity differed substantially; it would then be preferable to use the term ‘Zendism’ for the Iranian religion of the Arsacid times, which is in reality a later form of Zoroastrianism in which theological exegesis (Zend Avesta meaning interpretation of Avesta) prevailed over the original faith, and the Avestan text took mainly a moral connotation and value within the socio-religious environment of those days.

The Zend commentaries of the Avestan texts, which definitely originate from the spiritual-religious background of the Arsacid Parthian (and not Sassanid) times, do reflect theological concepts and world views closer associated with Tengrism. About:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zend

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Avestan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Avestan_alphabet

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pazend

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Middle_Persian

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Middle_Persian_literature

Zendism was definitely opposite to Mithraism, although perhaps not in the very strict form for which the Achaemenid emperors became famous. But it was mainly in Arsacid times that Mithraism expanded enormously both, southeastwards (India) and westwards (Caucasus, Anatolia, Syria, Greece, Europe, Rome and the Roman Empire). This does not mean that there were no Mithraic Magi left in Iran; their existence proved to be the main reason for palatial turmoil, sacerdotal plots, social unrest, and internal strives. Undoubtedly, the Magi were the absolute embodiment of Ahriman (: the evil) for the Arsacid rulers, pretty much like they had been an abomination for the Achaemenid monarchs.

In this regard, it is essential to point out that ‘Mithra’ (or ‘Mehr’) in Zoroastrianism and ‘Mithra’ (or ‘Mehr’) in Mithraism are two absolutely different divinities – pretty much like Jesus in Manichaeism, Mandaean religion, Gnostic Christianity, Roman & Eastern Roman Christianity, Nestorian Christianity, and Islam is not one being but many divergent entities or forms of divinity, each with dissimilar attributes. It goes without saying that for any concept or aspect of Tengrism, which is also a markedly monotheistic system, Mithra is a religious disgrace.

More specifically, I have to point out that within the context of Zoroastrianism, ‘Mithra’ (or ‘Mehr’) is a subordinate form of divinity that constitutes merely an expression of the unfathomable benevolence and omnipotence of Ahura Mazda, and as such it bears solar attributes. Contrarily, within the context of Mithraism, this divinity gets emancipated, becomes independent, and turns out to be the central recipient of cult, while a series of abominable and sacrilegious acts are attributed to him, notably the blasphemy of tauroctony which is part of the Mithraic eschatology. Due to the polytheistic nature of Mithraism, Mithra is intrinsically and extensively mythologized; this is so because there cannot be true polytheism without numerous narratives which attract the adoration of the faithful, and in the process, they prevent believers from focusing on the spiritual exercises, the moral principles, and the basic narratives of Cosmogony, Cosmology and Eschatology. In Mithraism, Ahura Mazda still exists as an inactive divinity of the old time, like the Roman dei otiosi.

At this point, it is essential to make one clarification; the well-known, theophoric name ‘Mithridates’, which was used by several Arsacid Parthian rulers, does not directly imply Mithraic affiliation. Certainly, the name means literally ‘given by Mithra’; it was also attested in Pontus, Commagene, Armenia and elsewhere. But every case of use is different. In some cases, it may involve the Zendist / Zoroastrian concept of Mithra; on other occasions, it may reflect a compromise among the Parthian Arsacid Empire’s imperial and the sacerdotal cliques, which were plunged in an endless conflict against one another.

Last, the use of the aforementioned theophoric name can eventually denote the pro-Mithraic tendency and affiliation of a Parthian monarch; there were indeed few Mithraists among the Arsacid rulers. This was an abomination for the monotheistic Parthian Zendist priests, and it appears that some of the pro-Mithraic Arsacid rulers were overthrown. The analysis of the reason(s) that stood behind the selection of a theophoric name in the Antiquity may be very long and complicated a topic, because usually these names heralded the nature of the imperial rule that was to be expected in terms easy to understand for the contemporaneous people and difficult to decode for modern scholarship. About:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theophoric_name

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mithridates_I_of_Parthia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mithridates_II_of_Parthia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mithridates_III_of_Parthia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mithridates_IV_of_Parthia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mithridates_V_of_Parthia

———– A SELECTION OF ARSACID PARTHIAN MONUMENTS ———

Hatra, NW Iraq: a major caravan city on the Silk Roads that prospered during the Arsacid Parthian times, being mainly inhabited by the local Aramaeans

A barrel vaulted iwan at the entrance at the ancient site of Hatra, modern-day Iraq, built c. 50 CE

Statue unearthed in Hatra, currently at the Tokyo National Museum: Aramaean amalgamation of Verethragna and an Aramaean deity into a Mithraic divinity similar to Artagnes, who is known to have been worshipped in Nemrut Dagh and Commagene in general

Temple of the Aramaean divinity Gareus, near Uruk, Southern Mesopotamia – near the borders of the vassal kingdom of Characene

Parthian ceramic oil lamp, from the province of Khuzestan, currently in the National Museum of Iran (Tehran)

Baal temple in Palmyra: a frieze relief

Grave towers in Tadmor / Palmyra / Phoinicopolis; known among Syrians as the ‘Valley of the Tombs’ (Wadi al-Qubur). Majestic funerary monuments bear witness to the extraordinary wealth of the great Aramaean caravan city (1st-3rd c. CE).

Statue of a young Palmyrene Aramaean in fine Parthian trousers; from a funerary stele at Palmyra / Tadmor, early 3rd century CE

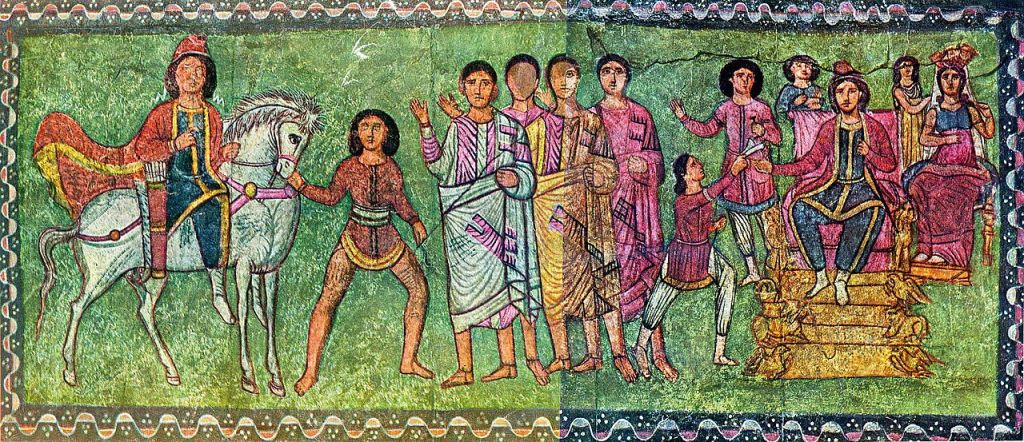

Mordechai and Esther. From the Aramaean Synagogue of Dura Europos (near Abu Kemal) on the Western bank of Euphrates River in Syria (right before the Syrian-Iraqi border): wall mural with representation of a story from the Book of Esther (early 3rd c. CE); artistic style known as ‘Parthian frontality’

—————————————————————————————————-

Download the chapter (text only) in PDF:

Download the chapter (pictures & legends) in PDF: