Pre-publication of chapter XV of my forthcoming book “Turkey is Iran and Iran is Turkey – 2500 Years of indivisible Turanian – Iranian Civilization distorted and estranged by Anglo-French Orientalists”. Along with Chapter XIV and Chapter XVI, Chapter XV belongs to Part Five {Fallacies about Sassanid History, History of Religions, and the History of Migrations}. The book is made of 12 parts and 33 chapters. Chapters XIV and XVI have already been made known in pre-publication here: https://megalommatiscomments.wordpress.com/2023/02/02/iran-turan-manichaeism-islam-during-the-migration-period-and-the-early-caliphates/ and

—————————————-

The two most ferocious enemies and spiritual masters delivered a merciless attack on one another: Kartir (above) as depicted in the relief of Naqsh-e Rajab, and Mani (below) as portrayed on his personal, rock crystal seal that bears the inscription “Mani, messenger of the messiah”

Long before the rise of the official Roman Christianity in the Roman Empire, the founder of Manichaeism, Mani invented a magnificent and most perplex Cosmogony and Eschatology that consisted also in an alternative dogma to the various Christian theological doctrines that contradicted one another; he postulated two absolutely different hypostases named Jesus, one material and perverse and another luminous and highly soteriological. Eventually, this could be the most formidable Iranian state religion to oppose Roman Christianity at all levels; but Manichaeism was totally opposed to all things Iranian in the first place.

Mani was an Iranian born in 216 CE in Tesifun (Ctesiphon), which was one of the Iranian capitals of the Arsacid and Sassanid times in Central Mesopotamia. Mani’s father was an Elcesaite Jewish Christian from Ecbatana (in Media, today’s Hamadan) and his mother was a Parthian. Following early spiritual revelations and major transcendental experiences that he had when 12 and 24 years old, in which his soul (usually described in Manichaean texts as the ‘spiritual twin’ or ‘syzygos’ in Greek Manichaean texts) called him to preach the true faith of Luminous Jesus, Mani traveled to India and spent some time there avidly studying all of the then known religions, doctrines, dogmas, faiths and esoteric systems of theurgy.

Afterwards, he returned to Iran and, in very young age, wrote a book titled ‘Shabuhragan’ (‘the book of Shapur’ – so the book was dedicated to the Sassanid Iranian Emperor), which became the major holy book of Manichaeism. Mani solemnly presented the mystical and revelatory book personally (242 CE) to Shapur I the Great (240-270 CE), one of the greatest monarchs of all times worldwide. This act was tantamount to divine designation of the Iranian monarch as the World Savior.

———————— Mani, Prophet of Manichaeism —————————

From left to right: Mani, Zoroaster, Buddha, Jesus; the four major prophets of the Manichaeans

The immaculate birth of Mani: he emerged from the breast of his mother

Mani’s Parents as depicted on a fragment of hanging scroll (decoration with gold and pigments on silk), 14th c. China

10th c. Manichaean Elects depicted on a wall painting from Gaochang (Qocho) near Turfan, Eastern Turkestan (Xinjiang)

Uighur Manichaean Elects from a 10th c. wall painting in Qocho, near Turfan, Eastern Turkestan (Xinjiang)

Manichaeans expressing adoration for the Tree of Life, which is located in the Realm of Light; drawing from a 10th c. wall painting in the Bezeklik Cave 38 (25 by Albert Grünwedel), near Turfan, Eastern Turkestan (Xinjiang)

Mani’s death (hanging from a palm tree in front of the Gundeshapur University) as depicted on a miniature from the ‘Shahnameh Demotte’ (also known as Great Mongol Shahnameh), from Ilkhanid Iran (ca. 1315); today in the Riza Abbasi Museum, Tehran

Mani presenting his painting to Bahram I: from the miniature of a 16th c. manuscript of a text by Ali-Shir Nava’i

——————————————————————————————————–

Prophet for his followers, who were the first in World History to stretch from the Atlantic to the Pacific, Mani (or Mani Hayya in Syriac Aramaic, i.e. Living Mani) was the world’s most multifaceted and multitalented mystic, spiritual preacher, universal visionary, magician, hierophant, erudite scholar, historian of religions, linguist, art theorist, painter, intellectual, thinker, and founder of religion of all times. In spite of his overwhelming rejection by the imperial priesthood of Iranian Mazdeism after Shapur the Great’s death, despite the enduring Christian anti-Manichaean hysteria, and notwithstanding the vertical disapproval of Manichaeism (mainly known as Manawiyah in Arabic – الـمـانـويـة) by Islam, Mani is by all criteria a unique and unsurpassed apostle.

At very young age, Mani was able to select elements from almost all the religions and esoteric systems of his times that existed between India, Central Asia, and the Mediterranean, to reshuffle them, to proclaim Zoroaster, Buddha, and Jesus as earlier prophets, to invent an entirely original Cosmogony, to entwine it with an apocalyptic revelation of the destiny of the Mankind, to add a fully structured eschatological soteriology, and to preach the entire system without the slightest tergiversation or nebulousness, adding to it a sacerdotal hierarchy and enriching / reconfirming it with impressive miracles (levitation, teleportation, faith healing, etc.).

In addition to the above and to the texts that he wrote in Syriac Aramaic and Middle Persian, Mani also invented an independent alphabetic writing system (presently known as the ‘Manichaean writing’); in this regard, it is essential to underscore that the term does not denote religious contents but the new, invented by Mani and based on Aramaic, alphabetic characters. The primary sources of Manichaeism and the Manichaean holy books were written in Syriac Aramaic, Middle Persian, and Manichaean writings. Translations were widely produced in the above writings and also in Parthian, Sogdian, Tocharian, Coptic, Greek, Latin, Old Uyghur, and Chinese.

Shapur I met Mani in-between his numerous battles and victories against the Kushan Empire and various other Asiatic states in the East and the Romans in the West. This was the best documented encounter between an emperor and a prophet in the History of the Mankind, almost 1000 years after Prophet Jonah was summoned by Sargon II, Emperor of Assyria and Emperor of the Universe. Shapur I did not adhere to Mani’s doctrine but evidently facilitated its diffusion.

To the eyes of the King of Iran and Aniran, Mani’s almost all-encompassing dogma could facilitate a unique opportunity to reunify the Achaemenid state’s territories from the plains of Ukraine to Egypt and from Western Anatolia to the Indo-Scythian kingdom’s lands, and further beyond, to the Pamir and the Tian Shan Mountains. Manichaeism could therefore function as the perfect tool of universal unification and the Manichaean Iran could be the melting pot of various Oriental nations, religions, esoteric systems, traditions and cultures, at a moment when west of Iran, the Roman Empire had already become a genuinely Oriental but counterfeit Empire.

Despite the fact that he was a co-ruler with his father (Ardashir I) and he therefore was viewed as a foremost pioneer of the widely supported Zoroastrian restoration, Shapur I was able to understand that his state religion, Mazdeism (a late form of Zoroastrianism that greatly differed from the religion of the Achaemenids), although enthusiastically attractive to his central provinces’ inhabitants, could never garner as many supporters from India, Central Asia, Africa and Europe as Mani’s new but practically more universalistic doctrine was clearly predestined to.

Manichaeism expanded rapidly and tremendously during the reign of Shapur I. As it was expected, there were few Persian adepts; but there were many Aramaeans, Turanians, Sogdians, Egyptians, Cappadocians and other Anatolians, Macedonians and Romans. Turanians across Central Asia and Siberia particularly embraced the new faith, which could prevail worldwide, if Shapur the Great’s successors followed his farseeing attitude. But a formidable Turanian mystic had deliberately seen fit to do otherwise: Kartir (or Kerdyr). Apparently, his will lay elsewhere, and this fact changed World History, averting the Manichaeization of Mankind.

Hormizd I continued his father’s attitude, but ruled only for a year; there are several indications that he was under the influence or the guidance of Mithraic Magi and this may have brought a sudden end to his reign. Hormizd I rose to power under very dark circumstances, even more so because he was his father’s third son. Bahram I, who was Shapur the Great’s firstborn son, sided firmly with the powerful mystic, hierophant, and spiritual theoretician of the imperial Sassanid doctrine Kartir, who seems to have prepared the premature end of Hormizd I’s pro-Mithraic reign.

——————— The Gallery of the Unchallenged Sassanids ———————–

Illustration of a Firuzabad relief depicting Ardashir I’s victory over Artaban IV, the last Parthian Arsacid; made by the French Orientalist painter and traveler Eugene Flandin in 1840

The coronation of Ardashir I (224-242 CE); he receives the ring of kingship by Ahura Mazda

The illustrious relief of Shapur I’s victory (Urfa-Urhoy/Edessa of Osrhoene; 260 CE) of the Roman Emperor Valerian, who is depicted as kneeling in a most humiliating manner; Naqsh-e Rustam, the imperial Achaemenid burial site

Broader views

Colossal statue of Shapur I (reign: 240-272) in the Shapur Cave, near Bishapur (7 m high): it was carved from one stalagmite

The famous cameo of Shapur I’s victory over Valerian

Bust of Shapur II (reigned from 309 to 379); one of the longest reigning rulers in history, he was crowned on his mother’s womb.

The coronation of Ardashir II (379-383) as depicted on the relief of Taq-e Bostan Paradise (imperial garden); Ahura Mazda offers him the ring of kingship, whereas Mithra (Mehr) holds the barsom, a sacred object used in rituals.

Peroz I (reign: 457–484) hunting argali

Kavad I (reign: 488–496 and 498–531) hunting rams

Khusraw (Chosroes) I Anushirvan (‘Immortal Soul’; reign: 531–579) hunting

Coptic woolen curtain with representation of Khusraw I fighting Axumite Abyssinian forces in Yemen

Khusraw I

The Iranian ambassador (probably dispatched by Khusraw I) at the court of Yuan of Liang dynasty (梁元帝) in Jingzhou, early 6th c. in later representation

The rebellious son (against Hormizd IV) Khusraw II Parvez (reign: 590 and 591-628) in boar hunting

Picture and design from the ceiling of Ajanta Cave 1 with the representation of the Iranian ambassador (apparently dispatched by Khusraw II Parviz) at the court of the Dravidian king Pulakesin II (610–642) of Vatapi (the Badami Chalukya kingdom)

Coin of the last great Sassanid Emperor Khusraw II Parviz

This is one of the first Umayyad coins: minted in Basra (AH 56 675-6 CE) at the time of the first Umayyad caliph Mu’awiya I, it mentions the local governor Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad. The similarity with the imperial Iranian Sassanid coins, particularly those of Khusraw II Parviz, demonstrates the viciously anti-Islamic nature and character of all those who opposed Ali ibn Abi Taleb as the first caliph of the Islamic state, and ended up with the son of Prophet Muhammad’s worst enemy (Abu Sufyan) founding the Umayyad Caliphate in Damascus (i.e. far from Medina) and declaring himself as the “Khusraw of the Arabs”.

—————————————————————————————————————–

With the rise of Bahram I, every sense of tolerance disappeared from the Sassanid Empire once for all. Kartir’s influence and prevalence in imperial doctrinal matters and in their implementation took almost the form of a terror regime, also involving incessant pogroms of any other faith beyond Mazdeism, which was a form of late Zoroastrianism that was then thought to be the ‘genuine return to Achaemenid Zoroastrian orthodoxy’. Kartir contributed greatly to Mazdeism, but he was not the sole contributor; on the contrary, he was the only to conceptualize and contextualize an imperial doctrine of cosmological dimensions, heroic moral standards, and fully exuberant human commitment. For the Turanian founder and standard-bearer of Sassanidism, men live only to be heroes, and it cannot be otherwise.

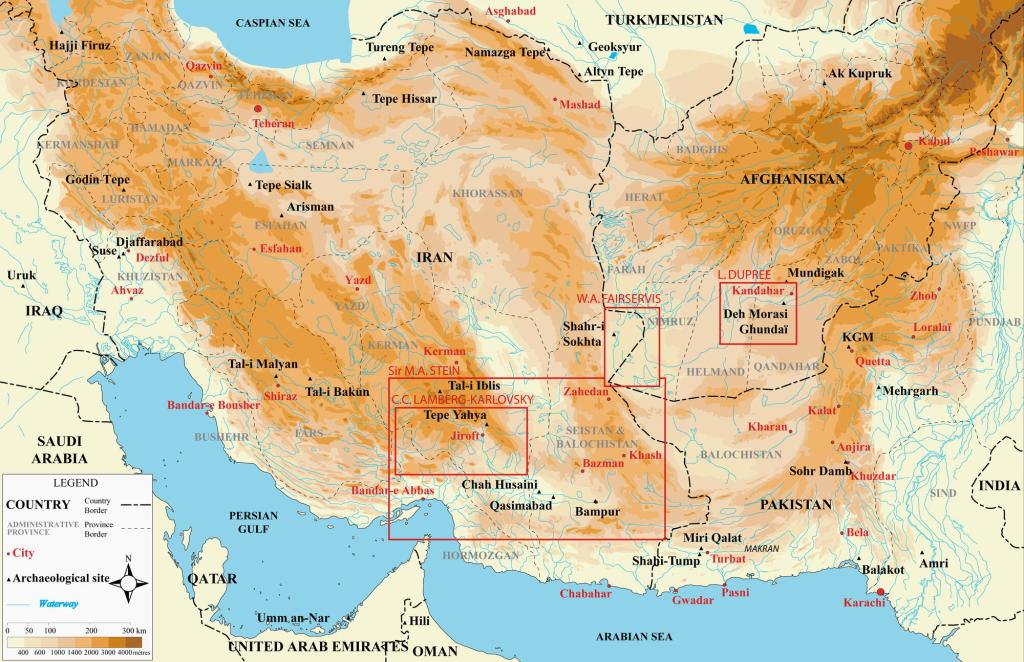

In an effort to reinstate the importance of Ancient Iran’s foremost religious center Adhur Gushnasp (where the original copy of the Avesta was kept and the original Fire was always burning), all Sassanid emperors, after being crowned in Tesifun (Ctesiphon), had to walk on foot the enormous distance (ca. 600 km) between their Mesopotamian imperial capital and their religious capital in the northern part of Zagros mountains (located at an elevation of ca. 3000 m, near today’s Takab, in NW Iran); this was something that neither the Achaemenids nor the Arsacids had done.

However, Kartir (in several texts, his name is spelled as Kerdyr) elaborated a state religious system of excessive veneration of the Iranian past with uniquely stressed references to ancestral heroism; Zoroastrian spirituality, Achaemenid metaphysics, and Arsacid ethics evaporated within Kartir’s religious invention in which only heroic deeds and ferocious battles were viewed as the designated way for Iranians to reach their ancestors’ universal apotheosis. Kartir’s imperial world conceptualization, vision, doctrine, and historical role generated a very divisive, sectarian environment across Iran; this situation has indeed some parallels with the Christological disputes (Docetism, Arianism, Monophysitism/Miaphysitism, Nestorianism, etc.) within the Roman Empire.

Kartir’s system, i.e. Imperial Mazdeism (or Sassanidism), demanded the imperative persecution of Mithraists, Christians, Gnostics, Manichaeans, Buddhists, and all the rest. The well-known Christian persecutions in the Roman Empire pale indeed with the destiny that Christians met in Sassanid Iran after the rise of Bahram I and the prevalence of Kartir. It was then that Mani, who was arrested when entering the Iranian city-university Gundeshapur, was imprisoned and later killed, eventually crucified. In this regard, I have to add that there have been several parallels -in historical, literary and theological sources- between Jesus’ entry to Jerusalem and Mani’s entry to Gundeshapur. However, not all the authoritative historical sources make state of Mani’s crucifixion.

Gundeshapur was the pre-Islamic world’s largest, richest and most advanced educational institution, library, museum, translation and scientific research center. Gundeshapur (lit. ‘the military city of Shapur’; گندیشاپور) was known in Syriac Aramaic as Beth Lapat, and it was located not far from Susa, east of Tigris river (few km south-east of today’s Dezful in SW Iran). The city-university was one of the few Iranian imperial centers and cities that were not destroyed during the Islamic invasion, and later most of its wealth and the academics were transferred to Abbasid Baghdad (750 CE) in order to set up the Islamic city-university Bayt al Hikmah (House of Wisdom).

Kartir’s ‘white terror’ and ‘purification pogrom’ shed rivers of blood and caused enormous migration movements among the Sassanid Empire’s minorities; Christians started leaving through Syria, Arabia and Yemen to India (like the ancestors of present day Malabar: the Malankara Nasrani or St Thomas Christians) or to Central Asiatic territories that were out of the Sassanid control. The Manichaeans spread worldwide; others moved to the Roman Empire, various groups settled in Caucasus, and larger numbers escaped in Central Asia, India and China. In a way, the diffusion of Nestorian Christianity and the spread of Manichaeism among the Turanians in Central Asia and Siberia are due to Kartir’s pogroms. The terrible persecution did not last only during Kartir’s lifetime; it was repeatedly carried out every now and then until the collapse (636-651 CE) of the Sassanid Empire.

Among Turanians and Muslims, but also within the context of Parsism, Kartir underwent almost a real process of damnatio memoriae; it is impressive that Tabari, Islamic times’ greatest historian, did not mention him at all, although he described religious persecution during the Sassanid era. Perhaps the reason for this compact silence about Kartir in Islamic sources, which ends only with Ibn al Nadim and his famous Kitab al-Fihrist, is due to two inscriptions of Kartir: one on a relief from Naqsh-e Rustam and the other from the Kaaba-e Zardosht (Zoroaster’s Kaaba), a sacred building in Naqsh-e Rustam.

— The major Sassanid high places of spirituality and sacred Imperial rule —

The only standing in its entirety building of the Sassanid times, Kaaba-e Zardosht, is located at Naqsh-e Rustam, in front of the tombs of the Achaemenid emperors that are hewn in the rock (few kilometers northwest of Parsa/Persepolis).

Istakhr: the few remains of the grandiose Sassanid capital which was located not far from Parsa (Persepolis), the ancient Achaemenid capital, in Fars

Istakhr

Adhur Gushnasp – Praaspa – Takht-e Suleyman (the ‘throne of Solomon’ as per the Islamic traditions): the sublime religious capital of Zoroastrian Orthodoxy was located in the northern part of the Zagros Mountains; the Sassanid emperors were walking from Tesifun (Ctesiphon) in Central Mesopotamia to reach the shrine where the only copy of the Avesta was guarded.

Takht-e Suleyman is located near Takab, at an elevation of 3000 m

Zendan-e Suleyman (‘the prison of Solomon’) is an ateshgah (fire temple), close to the Sacred Lake and the enclosure of Takht-e Suleyman.

Tesifun (Ctesiphon), in today’s Central Iraq (25 km south of Baghdad): Taq-i Kasra is the major remaining monument from the second Sassanid capital, which was the world’s most populous city during the period 550-630 CE.

Taq-i Kasra (طاق كسرى; also known as Ayevan-e Kesra/ایوان خسرو; Iwan/Arch of Khusraw)

Taq-e Bostan (5 km from Kermanshah): the Sassanid Paradise (imperial garden, which was established after the axioms of the imperial doctrine and the prescriptions of the Zoroastrian cosmological conceptualization), left an irrevocable impact on Iranians, before and after Islam. The Sassanid arches, reliefs and inscriptions are the major monuments around the Sacred Lake, but Islamic times’ Iranian-Turanian dynasties left also their input.

Taq-e Bostan

Shushtar, near Susa: the remains of an impressive hydraulic system established during the Sassanid era

The Mithraic temples at Bishapur, near Kazerun, in the southernmost confines of Zagros

The Sassanid walls and fortifications at Derbent (Eastern Caucasus), in today’s Russia

Near Zabol and the tri-border area (between Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan), Kuh-i Khwajah (کوه خواجه) is a major Iranian site in front of the Sacred Lake Harun.

Kuh-i Khwajah (Mount Khajeh)

———————————————————————————————————————-

In these inscriptions, Kartir makes state of his miraculous ascent to the heaven, a spiritual event later reproduced within Arda Wiraz Namag, a Sassanid times’ sacred book of Mazdeism, this time about the pious mystic Arda Wiraz. The issue of divine ascent to the heaven (known in Arabic as Isra and Mi’raj) was narrated later within the Quran about Prophet Muhammad (in chapter 17, Al Isra).

It is however interesting that Kartir’s (or Kerdyr’s) name has evident Turanian mythological meaning, but a very negative one (Ker). And in the famous relief of Naqsh-e Rajab, Kartir is depicted with his right hand making the well-known but ages-old sign of Bozkurtlar (‘Gray Wolves’).

Kartir’s inscription on the Kaaba-e Zardosht

Kartir depicted on the Naqsh-e Rajab relief; he apparently makes the very well known sign of the Bozkurtlar with his right hand.

The early diffusion of Manichaeism in Alexandria, NW Africa, and Europe makes it clear that, if Mani’s religion had even minimal support, let alone sponsorship, from the Sassanid state, it would supersede all other religions, faiths and esoteric systems across the Roman Empire. Tolerance toward Manichaeism ended in Sassanid Iran in 271 CE. And yet, the diffusion of the Manichaean faith across the Roman Empire was such that in 296 CE the Roman Emperor Diocletian had to issue a decree, ordering the slaughter of all Manicheans and the destruction of their books.

In the last three-four decades of the 3rd c., a great number of Aramaeans, Anatolians, Egyptians, Berbers of Northern and Northwestern Africa, Macedonians and Romans were Manichaean. As per the Roman Emperor’s description, the Roman Empire was shaken from its foundations. On 31st March 302, the leading Manicheans of Alexandria were burnt alive. During the Christianization of the Roman Empire, Manichaeism continued spreading from North Africa to Iberian Peninsula, Gaul and throughout Europe.

Many Manichaean ‘elects’ (: monks) existed already in Rome. And Fathers of the Christian Church were Manichaean for some years, like St. Augustine of Hippo. Manichaeism was a well-organized church with bishops, monks and sacerdotal hierarchy; several Christian Roman Emperors, like Theodosius I (379 – 395 CE) had to issue decrees and undertake campaigns to prevent Manichaeism from supplanting Christianity. However, the extent of Manichaean impact on Christian theology is another, totally different topic, which is vast and tenable.

This shows that, speaking about ‘one more Iranian religion’ spread across the ‘West’, namely the Balkans, Italy, and other parts of Western Europe, an unbiased scholar refers to Manichaeism, which -in addition to Mithraism- left an everlasting impact on Western Europe. In fact, during the so-called ‘Medieval times’ (which should be properly named ‘Christian and Islamic times’) in Central, Western and Southern Europe, the official religion (Christianity) and its true challenge and religious opposition (Manichaeism) were both of Oriental origin, nature and character. This undeniable fact highlights the Oriental impact on European civilization, thus rendering Europe an annex of Asia. In fact, Manichaeism determined European History and Civilization more than any indigenous religion or philosophy. It is true that for a moment, Manichaeism seemed to be extinct in the Western Roman Empire (around the 5th c.) and in the Eastern Roman Empire (during the 6th c.). However, it resurfaced soon afterwards.

The expansion of the Sassanid Empire of Iran

Eastern Roman Empire (395-1453), Sassanid Empire of Iran (224-651), and the Rashtra Empire of the Gupta dynasty (ca. 270-550)

General reading and bibliography can be found here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mani_(prophet)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manichaeism

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manichaean_alphabet

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Three_Seals_(Manichaeism)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shabuhragan

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shapur_I

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arzhang

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gospel_of_Mani

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elcesaites

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Al-Mada%27in

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hormizd_I

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bahram_I

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bahram_II

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diocletianic_Persecution#Manichean_persecution

https://iranicaonline.org/articles/kartir

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kartir

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kartir%27s_inscription_at_Naqsh-e_Rajab

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naqsh-e_Rajab

https://tr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ker

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gundeshapur

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint_Thomas_Christians

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Damnatio_memoriae

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_of_Arda_Viraf

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isra_and_Mi%27raj

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wolf#In_culture

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ergenekon

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grey_Wolves_(organization)#Name_and_symbolism

——————————- Sassanid Iranian Art —————————

Sassanid silk twill textile with the representation of the holy bird Simurgh whose name means “thirty birds”; Simurgh was the emblem of the Sassanid Empire of Iran. The sacredness of Simurgh survived during Islamic times.

Sassanid silver plate with representation of the holy bird Simurgh

Silver plate showing lance combat

Silver cup with a hunting Shah

Aramaean Christian cornelian gem of the Sassanid times with representation of the Biblical theme ‘the Sacrifice of Abraham’

Head of Sassanid scepter

Relief with a high ranking Sassanid official

Wall paintings from Kuh-i Khwajah

Relief over the Arch of Taq-e Bostan with angelic divinities

———————————————————————————————–

Download the entire chapter (text only) in PDF:

Download the entire chapter (with pictures and legends) in PDF: