Pre-publication of chapter XIX of my forthcoming book “Turkey is Iran and Iran is Turkey – 2500 Years of indivisible Turanian – Iranian Civilization distorted and estranged by Anglo-French Orientalists”; chapters XVII, XVIII, XIX and XX form Part Six (Fallacies about the Early Expansion of Islam: the Fake Arabization of Islam) of the book, which is made of 12 parts and 33 chapters. Chapter XVII and XX have already been pre-published.

Until now, 15 chapters have been uploaded as partly pre-publication of the book; the present chapter is therefore the 16th (out of 33). At the end of the present pre-publication, the entire Table of Contents is made available. Pre-published chapters are marked in blue color, and the present chapter is highlighted in gray color.

In addition, a list of all the already pre-published chapters (with the related links) is made available at the very end, after the Table of Contents.

The book is written for the general readership with the intention to briefly highlight numerous distortions made by the racist, colonial academics of Western Europe and North America only with the help of absurd conceptualization and preposterous contextualization.

———————————————————

Bosra (South Syria), Bahira Monastery

This process is associated with the fabrication of numerous fake terms, such as ‘Muhammedanism’, ‘Arab invasions’, ‘Arab conquests’, ‘Arab civilization’, etc. also involving the denigration of Islam as ‘religion of the Arabs’. The ‘Arabization’ of Islam is a paranoid Western Orientalist effort to reduce Islam to the level of a religion of just one nation, which – in addition – was the realm of repugnant barbarians; that’s why Orientalists and Islamologists always tried to portray the early Islamic invasions as ‘Arab’. About the reasons for which the initial Arab – Yemenite invasions (633-638) were successful, I already spoke in the previous chapter XVII (Iran – Turan and the Western, Orientalist distortions about the successful, early expansion of Islam during the 7th – 8th c. CE; see sections VI to X).

But there is certainly more to it. First, among the Islamic armies’ soldiers, who advanced after 640 either in the direction of the Iranian plateau and Caucasus or toward Egypt, the Arabs constituted already the minority. Most of the soldiers of the Islamic armies after 640 were Yemenite, Aramaean, and Axumite converts and, speaking about the Islamic armies two decades later (after 661), one has to add also new Turanian and Egyptian converts.

Major centers of Aramaean Syriac Jacobite (Monophysitic/Miaphysitic) Christianity in 7th c. CE Syria and Mesopotamia

In the Umayyad Caliphate, Medieval Greek and Syriac Aramaic were the two official languages, while Arabic was only the religious language for the Muslim minority. And the Arab warriors, who settled in Syria, Mesopotamia, Palestine, Egypt, Iran, and elsewhere, were so few that they were racially-ethnically assimilated with the local populations. The gradual, linguistic Arabization of the local populations in Yemen and in the formerly Eastern Roman provinces of the Orient was due to the fact that Arabic was the religious language.

In the lands where Islam was spread and became the official religion, there was no Arab culture diffused, because as I already said (chapter XVII, section I), to accept Islam the Arabs of Hejaz were de-Arabized and compactly Aramaized in the first place. This means that the ethnically Arab Muslim soldiers, who fought at Yarmuk and Qadissiyyah, were not culturally Arab anymore. They were indeed culturally Aramaized Arabs, thanks to their acceptance of Islam. There is no such thing as Arab culture in Islam.

Apparently, Arab culture existed before Islam in Hejaz and the desert, involving polytheistic cults, barbarian traditions, lawlessness and total absence of rudimentary civilization. To all the surrounding, civilized nations {namely the Yemenites, the Aramaeans, the diverse nations of Iran, the Eastern Romans, the Egyptians, the Sudanese Meroites (: Cushitic Ethiopians), the Axumite Abyssinians, and the Somalis of Other Berberia and Azania}, the pre-Islamic Arabs were known as the only barbarians of the wider region, and this was valid for many long centuries.

Homs/Emessa, Syria: Saint Mary Church; seat of the Syriac archbishopric and also known as Church of the Holy Girdle, it is a historical Syriac monument built over an underground church that dates back to 50 CE. Homs is famous for its black stones and rocks of which this church and many early mosques were built.

It is enough for anyone to read the text of the Periplus of the Red (‘Erythraean’) Sea (an Ancient Greek text written by an Alexandrian Egyptian merchant and navigator of the 2nd half of the 1st c. CE), so that he gets a very clear picture. Paragraph 20 of the said text, particularly if compared with earlier or later parts of the text, is quite revelatory of the rightfully deprecatory view of the Arabs that all the other ancient nations had.

“Directly below this place is the adjoining country of Arabia, in its length bordering a great distance on the Erythraean Sea. Different tribes inhabit the country, differing in their speech, some partially, and some altogether. The land next the sea is similarly dotted here and there with caves of the Fish-Eaters, but the country inland is peopled by rascally men speaking two languages, who live in villages and nomadic camps, by whom those sailing off the middle course are plundered, and those surviving shipwrecks are taken for slaves. And so they too are continually taken prisoners by the chiefs and kings of Arabia; and they are called Carnaites. Navigation is dangerous along this whole coast of Arabia, which is without harbors, with bad anchorages, foul, inaccessible because of breakers and rocks, and terrible in every way. Therefore we hold our course down the middle of the gulf and pass on as fast as possible by the country of Arabia until we come to the Burnt Island; directly below which there are regions of peaceful people, nomadic, pasturers of cattle, sheep and camels“.

The text is to be found online here (translation by Wilfred H. Schoff):

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Periplus_of_the_Erythraean_Sea#Periplus

This barbarism took an end with the preaching of Prophet Muhammad, who transferred Aramaean culture, education, intellectuality and spirituality among the Arabs. All the themes and topics discussed by Prophet Muhammad, either in his revelations (Quran) or in his explanations (Hadith), were Aramaean. Of course, and with reference to developments taking place during the middle of the 7th c., there was an evident differentiation between a) Christian Aramaeans and b) Muslim Aramaeans and Muslim Arabs; but the differentiation was only religious, and not cultural. Culturally, the groups a) and b) were identical; and religiously they differed only partly and not fundamentally. But the perfidious colonial Orientalists have always been intentionally oblivious of this fact.

Founded by Mor Mattai the Hermit in 363 CE, Mor Mattai Monastery is situated 20 km north of Mosul and consists in a major center of Aramaean Syriac Jacobite culture and faith.

Deyrulzafaran (or Derzafaran; ‘the Saffron Monastery) is mainly known as Mor Hananyo Monastery, being located 5 km from Mardin (SE Turkey) in the famous Tur Abdin region, major center of Aramaean culture, faith and letters. In the Antiquity, there was a temple dedicated to the Assyrian-Babylonian and later Aramaean divinity Shamash; it was then converted to fortress by the Romans. The Syriac monk Mor Shlemon turned it into a monastery in 493 CE. Finally in 793, the bishop of Mardin and Kfartuta, Mor Hananyo, renovated it.

Surely there are ancient Oriental parallels to what happened to the Arabs in the early 7th c.

The Aramaeans and the Phoenicians, the Egyptians and the Anatolians, the Greeks and the Romans – all those who accepted the preaching of Jesus and belonged to the early Christian communities (except for the Jewish converts) – were culturally Hebraized (in the first two centuries of our era).

There is no such thing as Aramaean or Phoenician or Egyptian or Greek or Roman culture in Early Christianity. Aramaean culture revolved around Astarte or the ‘Syrian Goddess’, Baal, and many other Aramaean deities, myths and concepts; Phoenician culture was developed around Baal and other local divinities and myths; Egyptian culture was related to Isis, Osiris, Horus and the Heliopolitan religion or the Theban dogma of Amun or the Memphitic cult of Ptah or the Hermupolitan Ogdoad. Greek culture (which had earlier involved a highly politicized theater, Olympic games, philosophy, calamitous indifference for religion, and quasi-total ignorance of spirituality) and Roman culture were already heavily impacted by numerous Oriental religious, esoteric, spiritual and cultural-behavioral systems. Then, the diffusion of Early Christianity among them (up to the middle of the 2nd c. CE) consisted in cultural Hebraization.

What happened culturally to Arabs with their acceptance of Prophet Muhammad’s preaching had occurred already to the Aramaeans, the Phoenicians, the Egyptians, the Anatolians, the Greeks and the Romans, who accepted Early Christianity in the 1st – 2nd c.

Similarly, the Ancient Hebrews were not exempt of overwhelming foreign cultural impact. When in Egypt, they were heavily impacted by Atenism (also known as Amarna monotheism), which was the official, aniconic and monotheistic religion of Pharaoh Akhenaten in the middle of the 14th c. BCE. Excerpts from the Hymns to Aten, which were composed in Ancient Egyptian and written in hieroglyphic writing by the pious monotheist and great reformer Pharaoh, were later reproduced, word by word, in the Psalms of the otherwise ‘Hebrew’ Bible.

At this point I have to also add that Pharaoh Amenhotep IV (1353–1336), after his fourth year of reign, changed his theophoric name to Akhenaten, so that it does not contain the first component, which – as name of the polytheistic Theban religion’s main god Amun – was considered as an abomination by the Egyptian monotheists, after the solemn proclamation of Atenism.

And who were the Ancient Hebrews after all? Who was Abraham? An early 2nd millennium BCE Babylonian (from Ur, Southern Mesopotamia), who abandoned his land in order to preserve his monotheistic faith and openly reject the polytheistic religion that was imposed there at the time. The Assyrian-Babylonian impact on what is called Ancient Hebrew religion or Judaism is absolute, compact, and irreversible. The Old Testament is an Assyrian-Babylonian cultural, religious, intellectual, and spiritual byproduct.

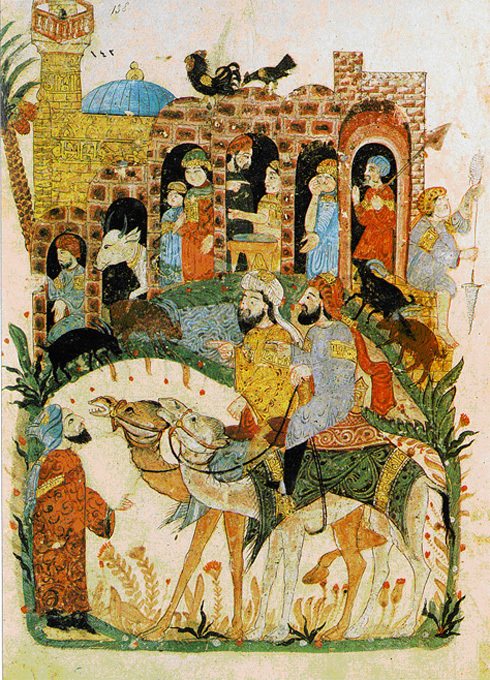

Discussion near the mosque of a village (from the 43rd maqamah of the Maqamat al-Ḥariri); by the Iraqi painter and calligrapher Yahya ibn Mahmud al-Wasiti (13th c.); the illustrations of the famous Muslim painter show that rural life continued following exactly the same Aramaean patterns before and after the diffusion of Islam.

The aforementioned approach is extremely embarrassing to colonial Orientalist forgers and to Western pseudo-Christian Evangelical, Taliban-fashion theologians, who should rather be considered as the real instigators and the original perpetrators of Islamic terrorism, which they have studiously and scrupulously produced because of their vicious anti-Islamic hatred that they have ceaselessly diffused. That is why it is vitally important for them to stick the label ‘Arab’ onto the entire phenomenon of ‘Islamic Civilization’, ‘Islamic History’, ‘Islamic religion’, and ‘Islamic armies’.

However, there is even more to it, if one examines the fundamentals of the divine revelation as spelled out in Islam’s holy text and the associated explanations. The historical reality is that Muhammad, either one accepts him as prophet or not, never pretended that he was preaching a ‘new’ religion; according to his revelation (the Quran) and explanations (the Hadith), Islam (lit. ‘submission to God’) was the only true faith (‘religion’) of Adam. In fact, according to the prophet Muhammad’s world conceptualization, there has been only one religion in the History of Mankind; it was preached by various prophets, either they were/are known to humans as such or not. All prophets were sent by God to correct deviations, because beyond the only and true religion (which involves total devotion to God), there have been across the ages numerous deformations, distortions, deliberate alterations, and pernicious modifications of the true religion, and of the preaching / revelation of the various earlier prophets.

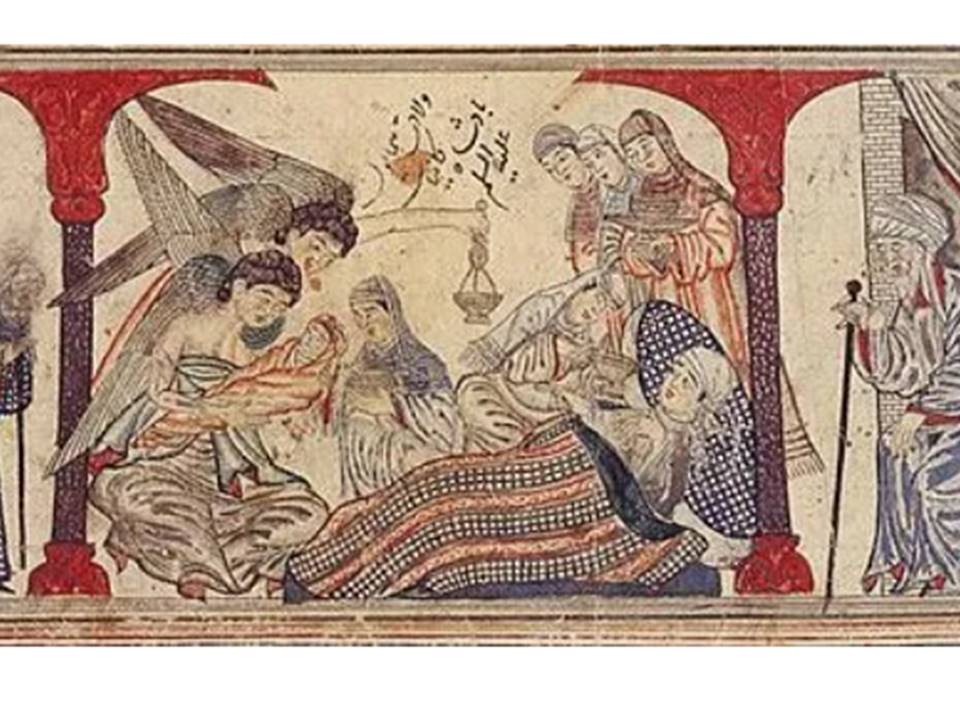

The birth of prophet Muhammad in presence of humans and angels; miniature illustration on vellum from Rashid al-Din Hamadani’s famous masterpiece Jami’ al-Tawarikh (lit. ‘Compendium of Chronicles’), which is also known as ‘Universal History’ (Tabriz-Iran, 1307)

Prophet Muhammad on his death bed (Jami’ al-Tawarikh)

Prophet Muhammad reveals to Ali (both protected by halos of golden flames) secrets he unveiled during Mir’aj (transcendental travel to the spiritual universe); from the Ottoman Turkish ‘Tarjuma-i Thawaqib-i manaqib’ (translation of stars of the legend), which was ordered by Sultan Murad III (1574–1595) to be done (in 1590) from the Farsi abridgement (14th c.) of Aflaki; found in Baghdad and purchased by Pierpont Morgan in 1911 (MS M.466, fol. 96r). According to this tradition, ten thousand of the hundred thousand secrets were revealed to Ali as the rightful successor to prophet Muhammad. Ali had difficulty keeping them, and that is why he shouted them into a well; however, a young man made a flute from the tree, which grew from the reed in the well. People came from all over to hear the young man play, and then prophet Muhammad requested to hear the youth perform, declaring that his notes “were the interpretation of the celestial mysteries that he had confided to Ali”. The flute was used ever since as part of the Mevlevi ritual dance (samaa). Jalal ad-Din Rumi has apparently borrowed the story of the barber, who shouted the secret of the Phrygian King Midas’ donkey ears into a hole over which reeds grew, and subsequently the winds whispered the secret to all. The early spirituality of the true Islam was greatly appreciated by Muslims of the Golden Era of Islamic Civilization, but there is nothing Arabic in it.

It is the aforementioned, outspoken universality of Islam that has deeply upset and dramatically embarrassed Western Orientalist forgers, colonial radicals, Catholic-Jesuit schemers, and materialist-atheist extremists. And this explains why they tried to imitate some Eastern Roman historians of the 8th c., who collectively called all the Muslims ‘Saracens’, a deprecatory term that is historically false enough to reveal either the ignorance or the evilness of the users.

However, to Eastern Roman Christian Orthodox theologians, like John Damascene (or John of Damascus), Islam was merely the latest Christological heresy. This is what Vatican, the pseudo-Christian Evangelicals, and the anti-Jewish Zionists do their ingenious best to conceal; because the Eastern Roman Christian Orthodox truth destroys their absurd lies and diabolical conspiracies.

The multiply controversial gold coins of the Umayyad caliph Abd al Malik ibn Marwan (reign: 685-705); during his reign, there was an apparent effort to impose Arabic as the official language of the divided Caliphate and to replace Christian signs (notably the Cross) with the declaration of Islamic faith. However, the caliph ruled only on a small part of the territory that most people usually see as enormous on the mostly false maps of the Umayyad Empire, and this was due to the fact that he was facing a multiple revolt. Even worse, following a defeat, he had to be tribute to the Eastern Roman Empire. But to his greatest surprise, when he tried to pay with these new coins, the Roman Emperor Justinian II (reign: 685-695 and 705-711) refused to accept them because they were of an unknown type and of evidently unacceptable character. This attitude triggered a new war; the offense was not only the absence of Christian symbols, but also the Arabic inscription with the Islamic declaration of faith (‘bismallah, la illah illa-allah muhammad rasul allah’, i.e. ‘in the name of God, there is no god but God alone; Muhammad is His messenger’) on the reverse and the presence of three standing figures on the obverse.

As there no names written on the coins, every discussion is basically a matter of assumption, but there are specialists, who suggest that the three figures are none else than prophet Muhammad (center), Abu Bakr, and his paranoid daughter Aisha, who was the last wife of the prophet. Abu Bakr was indeed one of the early followers of Islam (the very first being Ali ibn Abi Taleb, who was the prophet’s cousin and son-in-law). Abu Bakr, was selected by a small group of vicious Meccan renegades at the time prophet Muhammad was dying – in straightforwardly anti-Islamic rejection of the solemn investiture of Ali by the prophet at Ghadir Khumm on the 16th March 632 (18 Dhu al-Hijjah), i.e. only three months before prophet Muhammad’s death (8 June 632), in the 11th year of the Islamic calendar (Anno Hegirae). The heinous, anti-Islamic nature and practices of the Umayyad dynasty, which existed only after the massacre of the rightful heir of Ali and against the will of the quasi-totality of the Muslims, is the reason for which this interpretation can be considered as possibly correct.

The much loathed and decried, lawless and illegitimate caliph sought to ‘prove’ that he was the rightful ruler and that he represented a line of succession approved by prophet Muhammad. Of course, this was preposterous because at the very end of the prophet’s life, Abu Bakr acted openly and deliberately against Muhammad’s will, whereas the rancorous and hysterical Aisha supported the killers of Fatima and later of Ali. An extra reason for which we can accept this effort of interpretation is the fact that this shameless and absolutely anti-Islamic depiction caused an unprecedented outcry (because it was taken as a clear sign of overwhelming rejection of Islam by the court at Damascus) up to the point that these blasphemous coins were all ordered to be destroyed shortly after they were minted. As his wretched empire experienced divisions, civil wars, and real trichotomy, the shy and coward Abd al Malik ibn Marwan decided not to further risk his otherwise useless throne.

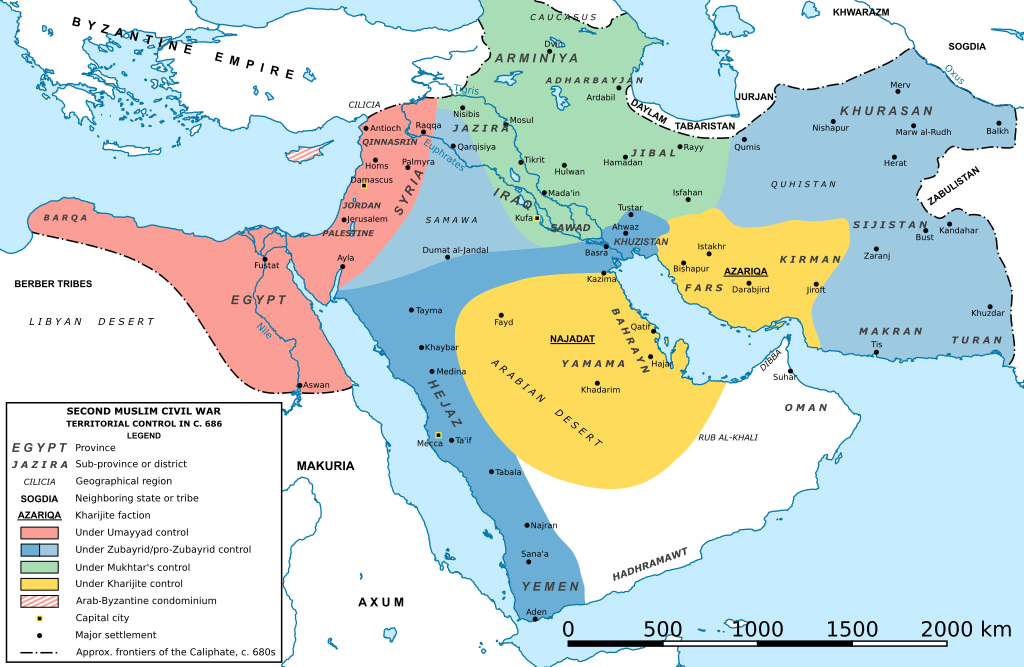

The supposedly powerful (according to Western colonial liars and forgers) Umayyad Empire was a multi-divided terrain of which Abd al-Malik Marwan controlled only a small portion (highlighted in red); the lands controlled by his opponents al-Mukhtar and al-Zubayr are colored in green and blue; and the territory under Kharijite power is shown in yellow. This chaotic period (680-692) is typically called ‘Second Fitna’, i.e. conflict, sedition, or civil strife; the word has many connotations, but the most accurate description of the historical fact would be ‘civil war’.

————————————————–

FORTHCOMING

Turkey is Iran and Iran is Turkey

2500 Years of indivisible Turanian – Iranian Civilization distorted and estranged by Anglo-French Orientalists

By Prof. Muhammet Şemsettin Gözübüyükoğlu

(Muhammad Shamsaddin Megalommatis)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE

CONTENTS

PART ONE. INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER I: A World held Captive by the Colonial Gangsters: France, England, the US, and the Delusional History Taught in their Deceitful Universities

A. Examples of fake national names

a) Mongolia (or Mughal) and Deccan – Not India!

b) Tataria – Not Russia!

c) Romania (with the accent on the penultimate syllable) – Not Greece!

d) Kemet or Masr – Not Egypt!

e) Khazaria – not Israel!

f) Abyssinia – not Ethiopia!

B. Earlier Exchange of Messages in Turkish

C. The Preamble to My Response

CHAPTER II: Geopolitics does not exist.

CHAPTER III: Politics does not exist.

CHAPTER IV: Turkey and Iran beyond politics and geopolitics: Orientalism, conceptualization, contextualization, concealment

A. Orientalism

B. Conceptualization

C. Contextualization

D. Concealment

PART TWO. EXAMPLE OF ACADEMICALLY CONCEALED, KEY HISTORICAL TEXT

CHAPTER V: Plutarch and the diffusion of Ancient Egyptian and Iranian Religions and Cultures in Ancient Greece

PART THREE. TURKEY AND IRAN BEYOND POLITICS AND GEOPOLITICS: REJECTION OF THE ORIENTALIST, TURKOLOGIST AND IRANOLOGIST FALLACIES ABOUT ACHAEMENID HISTORY

CHAPTER VI: The fallacy that Turkic nations were not present in the wider Mesopotamia – Anatolia region in pre-Islamic times

CHAPTER VII: The fallacious representation of Achaemenid Iran by Western Orientalists

CHAPTER VIII: The premeditated disconnection of Atropatene / Adhurbadagan from the History of Azerbaijan

CHAPTER IX: Iranian and Turanian nations in Achaemenid Iran

CHAPTER X: Iranian and Turanian Religions in Pre-Islamic Iran

PART FOUR. FALLACIES ABOUT THE SO-CALLED HELLENISTIC PERIOD, ALEXANDER THE GREAT, AND THE SELEUCID & THE PARTHIAN ARSACID TIMES

CHAPTER XI: Alexander the Great as Iranian King of Kings, the fallacy of Hellenism, and the nonexistent Hellenistic Period

CHAPTER XII: Parthian Turan: an Anti-Persian dynasty

CHAPTER XIII: Parthian Turan and the Philhellenism of the Arsacids

PART FIVE. FALLACIES ABOUT SASSANID HISTORY, HISTORY OF RELIGIONS, AND THE HISTORY OF MIGRATIONS

CHAPTER XIV: Arsacid & Sassanid Iran, and the wars against the Mithraic – Christian Roman Empire

CHAPTER XV: Sassanid Iran – Turan, Kartir, Roman Empire, Christianity, Mani and Manichaeism

CHAPTER XVI: Iran – Turan, Manichaeism & Islam during the Migration Period and the Early Caliphates

PART SIX. FALLACIES ABOUT THE EARLY EXPANSION OF ISLAM: THE FAKE ARABIZATION OF ISLAM

CHAPTER XVII: Iran – Turan and the Western, Orientalist distortions about the successful, early expansion of Islam during the 7th – 8th c. CE

CHAPTER XVIII: Western Orientalist falsifications of Islamic History: Identification of Islam with only Hejaz at the times of the Prophet

CHAPTER XIX: The fake, Orientalist Arabization of Islam

CHAPTER XX: The systematic dissociation of Islam from the Ancient Oriental History

PART SEVEN. THE FICTIONAL DIVISION OF ISLAM INTO ‘SUNNI’ AND ‘SHIA’

CHAPTER XXI: The fabrication of the fake divide ‘Sunni Islam vs. Shia Islam’

PART EIGHT. THE DISTORTED TERM ‘PERSIANATE’

CHAPTER XXII: The fake Persianization of the Abbasid Caliphate

PART NINE. FALLACIES ABOUT THE GOLDEN ERA OF THE ISLAMIC CIVILIZATION

CHAPTER XXIII: From Ferdowsi to the Seljuk Turks, Nizam al Mulk, Nizami Ganjavi, Jalal ad-Din Rumi and Haji Bektash

PART TEN. FALLACIES ABOUT THE TIMES OF TURANIAN (MONGOLIAN) SUPREMACY IN TERMS OF SCIENCES, ARTS, LETTERS, SPIRITUALITY AND IMPERIAL UNIVERSALISM

CHAPTER XXIV: From Genghis Khan, Nasir al-Din al Tusi and Hulagu to Timur

CHAPTER XXV: Timur (Tamerlane) as a Turanian Muslim descendant of the Great Hero Manuchehr, his exploits and triumphs, and the slow rise of the Turanian Safavid Order

CHAPTER XXVI: the Timurid Era as Peak of the Islamic Civilization, Shah Rukh, and Ulugh Beg, the Astronomer Emperor

PART ELEVEN. HOW AND WHY THE OTTOMANS, THE SAFAVIDS AND THE MUGHALS FAILED

CHAPTER XXVII: Ethnically Turanian Safavids & Culturally Iranian Ottomans: two identical empires that mirrored one another

CHAPTER XXVIII: Spirituality, Religion & Theology: the fallacy of the Safavid conversion of Iran to ‘Shia Islam’

CHAPTER XXIX: Selim I, Ismail I, and Babur

CHAPTER XXX: The Battle of Chaldiran (1514), and how it predestined the Fall of the Islamic World

CHAPTER XXXI: Ottomans, Safavids and Mughals: victims of their sectarianism, tribalism, theology, and wrong evaluation of the colonial West

CHAPTER XXXII: Ottomans, Iranians and Mughals from Nader Shah to Kemal Ataturk

PART TWELVE. CONCLUSION

CHAPTER XXXIII: Turkey and Iran beyond politics and geopolitics: whereto?

————————————————————-

List of the already pre-published chapters of the book

Lines separate chapters that belong to different parts of the book.

Iranian and Turanian Religions in Pre-Islamic Iran

https://www.academia.edu/105664696/Iranian_and_Turanian_Religions_in_Pre_Islamic_Iran

—————————

CHAPTER XI: Alexander the Great as Iranian King of Kings, the fallacy of Hellenism, and the nonexistent Hellenistic Period

CHAPTER XII: Parthian Turan: an Anti-Persian dynasty

https://www.academia.edu/52541355/Parthian_Turan_an_Anti_Persian_dynasty

CHAPTER XIII: Parthian Turan and the Philhellenism of the Arsacids

https://www.academia.edu/105539884/Parthian_Turan_and_the_Philhellenism_of_the_Arsacids

———————————

CHAPTER XIV: Arsacid & Sassanid Iran, and the wars against the Mithraic – Christian Roman Empire

CHAPTER XV: Sassanid Iran – Turan, Kartir, Roman Empire, Christianity, Mani and Manichaeism

CHAPTER XVI: Iran – Turan, Manichaeism & Islam during the Migration Period and the Early Caliphates

———————————-

CHAPTER XVII: Iran–Turan and the Western, Orientalist distortions about the successful, early expansion of Islam during the 7th-8th c. CE

CHAPTER XX: The systematic dissociation of Islam from the Ancient Oriental History

—————————————

CHAPTER XXI: The fabrication of the fake divide ‘Sunni Islam vs. Shia Islam’

https://www.academia.edu/55139916/The_Fabrication_of_the_Fake_Divide_Sunni_Islam_vs_Shia_Islam_

——————————————

CHAPTER XXII: The fake Persianization of the Abbasid Caliphate

https://www.academia.edu/61193026/The_Fake_Persianization_of_the_Abbasid_Caliphate

——————————————–

CHAPTER XXIII: From Ferdowsi to the Seljuk Turks, Nizam al Mulk, Nizami Ganjavi, Jalal ad-Din Rumi and Haji Bektash

————————————————

CHAPTER XXIV: From Genghis Khan, Nasir al-Din al Tusi and Hulagu to Timur

CHAPTER XXV: Timur (Tamerlane) as a Turanian Muslim descendant of the Great Hero Manuchehr, his exploits and triumphs, and the slow rise of the Turanian Safavid Order

CHAPTER XXVI: The Timurid Era as the Peak of the Islamic Civilization: Shah Rukh, and Ulugh Beg, the Astronomer Emperor

————————————————————————

Download the chapter (text only) in PDF:

Download the chapter (with pictures and legends) in PDF: